For years, scientists have been raising concerns about a 2017 paper that put forward a novel theory about dyslexia and spawned a range of products for people with the condition.

A new commentary published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B says there is no evidence to support the theory that dyslexia arises from symmetry in the distribution of photoreceptors in the left and right eyes.

That theory, first proposed by two physicists in the same journal, was the basis for patent filings on flickering eyeglasses, screens and lamps marketed for dyslexic children. The battery-powered glasses, dubbed the Lexilens, received an Innovation Award at the Consumer Electronics Show in 2020. That same year, France’s National Academy of Medicine awarded the researchers a prize for their work.

The new commentary, however, calls the 2017 study “highly problematic” and “likely not reproducible.”

The authors point out that the study failed to conduct an objective assessment of the dyslexic students it recruited, such as evaluating their baseline reading ability. They assert that the published methodology is confusing, contradictory and potentially biased because the participants were not properly randomized.

It is also unclear whether the study was approved by an institutional review board as required by the journal, the commentary says. The original article failed to disclose any details of the informed-consent procedure or the name of the institutional review board, noting only that it had been “conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.”

“This was a failure of the peer-review process,” says Florian Naudet, a psychiatrist and professor of medicine at the University of Rennes who co-wrote the commentary. “It should not have been published.” Naudet also notes that several independent trials have so far failed to find a benefit from the related products.

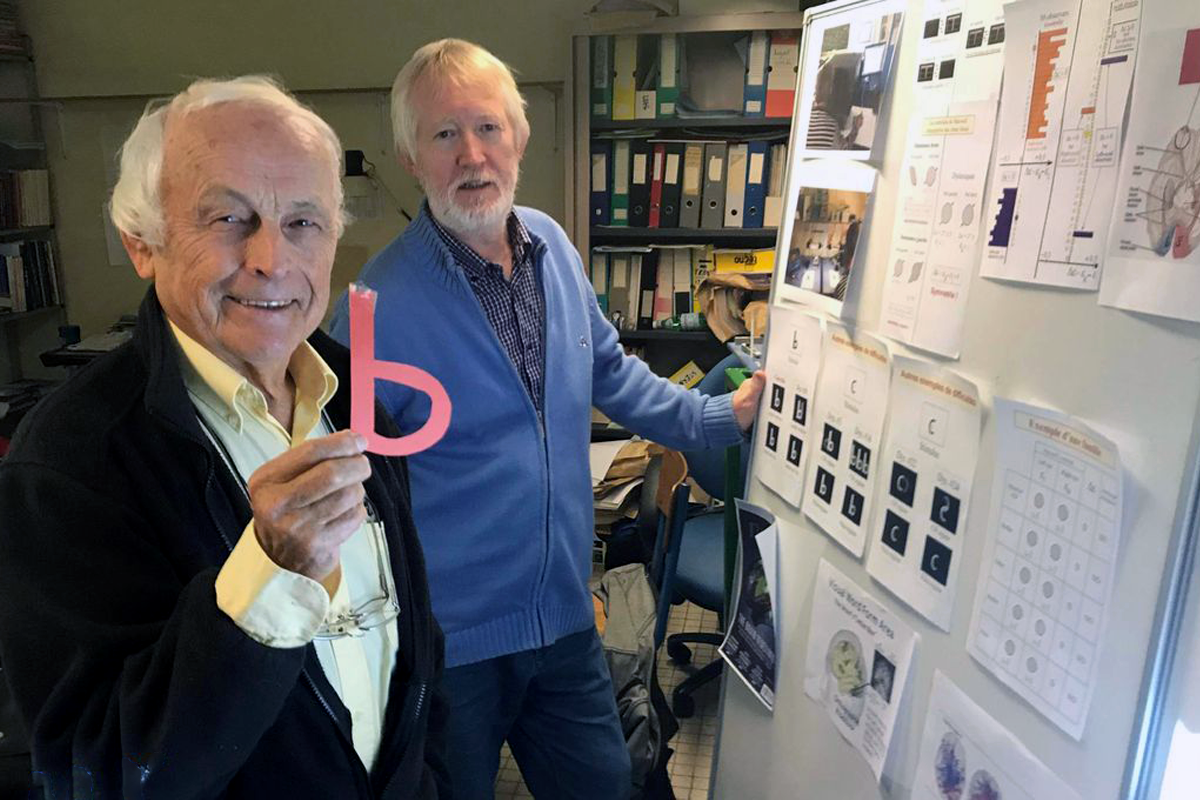

The originators of the theory, Albert Le Floch and Guy Ropars, also at the University of Rennes, did not respond to specific questions about their work but say they stand by their findings.

“Our physicists’ approach to dyslexia is robust,” they wrote in a joint email to The Transmitter, noting that the clinical studies conducted to date have been flawed. “Naudet’s comments do not discredit any of the scientific results from the six figures in our 2017 paper.”

T

wo commercial sponsors of the products that sprang from the 2017 paper have blocked researchers from publishing or sharing results from their own double-blind clinical trials, the investigators who oversaw those trials under a contract with the university have revealed to The Transmitter.The researchers, who were not paid by the companies, say they signed contracts suggesting that the results would be published and shared with participants. But when the trials were completed in 2021, the companies refused to waive a confidentiality clause in the contract.

“I was very upset by this,” says neurologist Catherine Allaire, who led one of the trials at Rennes University Hospital before her retirement. She found no evidence that a lamp being developed by the university’s technology transfer company, Ouest Valorisation, helps dyslexic children. “They never allowed us to publish these results.”

Lili Light for Life, which licensed the technology from Ouest Valorisation, provided The Transmitter with a customer satisfaction survey and noted that it is running a new trial in the United Kingdom.

Frederic Mouriaux, an ophthalmologist at the same hospital who ran a study on the Lexilens glasses, says that he was not even permitted to see the results, including whether the glasses could be leading to adverse outcomes.

In response to a formal request from Rennes University Hospital to publish the data and share it with the trial participants and their families, the company sponsor of the glasses, Abeye, wrote in a letter shown to The Transmitter that it would not share the data because Mouriaux’s study was flawed.

“The first study did produce some positive results, but not positive enough for my tastes,” says Michael Kodochian, Abeye’s CEO. In his view, a proper clinical evaluation of the Lexilens would include monitoring children’s reading ability over time as they develop their reading skills using the glasses. “The eyewear does not teach how to read or spell,” he says. “You cannot erase five years of struggling.” He says the company is planning a new study of the Lexilens but declined to provide any details about it.

“I can hear the sound of goal posts being desperately relocated,” says Dorothy Bishop, emeritus professor of developmental psychology at the University of Oxford and a co-author on the commentary. “If they need more time points to evaluate the Lexilens, then they should provide data to confirm that is the case.”

L

e Floch and Ropars came to the field without any special expertise in dyslexia, but they did have knowledge about lasers and an interest in an optical phenomenon known as Maxwell’s spot: If an observer stares at a purple screen, a reddish spot with a halo around it will appear in the center of their field of vision.Maxwell’s spot arises because the macula, the region on the retina with the highest concentration of photoreceptors, has a pigment that absorbs blue light. In fact, at the center of the fovea, the depression within the boundaries of the macula where vision is the sharpest, there are no blue cone photoreceptors, only red and green ones.

In their 2017 study, Le Floch and Ropars used their own invention, dubbed the foveascope, to create tracings of this spot in the left and right eyes of 30 children with dyslexia and 30 without. In all of the children without dyslexia, the spot was round in their dominant eye and somewhat elliptical in their non-dominant eye. By contrast, 27 of the dyslexic participants had nearly symmetrical round spots.