Larry Young, a neuroscientist known for illuminating oxytocin’s outsized role in social bonding, died of a heart attack last month at the age of 57.

In his 30-year career at Emory University, Young teased apart the neurobiology of love and relationships—from the receptors that make voles monogamous to the hormones that shape sociability in psychiatric disorders. He founded and directed both the Center for Translational Social Neuroscience and the Silvio O. Conte Center for Oxytocin and Social Cognition at Emory, and he helped establish the Laboratory of Social Neural Networks in Tsukuba, Japan.

“His impact has been enormous,” says Steven Phelps, professor of integrative biology at the University of Texas at Austin, who was Young’s first postdoctoral researcher at Emory. “He brought molecular biology to what we would call non-model organisms, the species that are normally neglected by mainstream science.”

Young also fostered collaborations through the many international conferences he organized, and he raised the public profile of neuroscience research through his dedication to science communication.

He served as a hub within the field of social neuroscience—someone who connected others across continents and research modalities—says Steve Chang, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Yale University. “Everyone feels there is now a giant hole.”

Y

oung grew up on a farm in Sylvester, Georgia, a small town that claims the title of “Peanut Capital of the World.” As a child, he loved animals and kept many pets—including, for a time, a possum that he carried around on his head, Young recalled on a podcast in 2022. He had thoughts of becoming a veterinarian but pivoted to medicine when, in his biochemistry classes at the University of Georgia, he became fascinated with genetics and how nature manages to translate a string of letters to the behaviors necessary for survival.In college, Young worked in a lab studying the peptides in mosquito brains that control the insects’ feeding behaviors. When one of his advisers told him that he couldn’t study the biochemistry of behavior, he recalled on the podcast, he took to the library, where he stumbled across a book on how hormones shape mating behaviors in fish and other animals. He contacted the book’s editor, David Crews, currently Ashbel Smith professor of zoology and psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, and in 1989 joined Crews’ lab at that institution to pursue a doctoral degree.

In his early research, Young studied how sex steroid hormone receptors influence mating in two species of lizards. “I like to ask questions and then find the species that is perfectly suited for that question. And then try to figure out how to bring all the tools to bear to that species,” Young said on the 2022 podcast.

That same approach led him to the species that he became best known for: the prairie vole. After graduate school, Young moved to Emory to work with Thomas Insel, who was then professor of psychiatry, on the role of the peptide vasopressin in prairie voles’ ability to form pair bonds. Prairie voles mate for life and raise offspring together. But other species of voles, such as the montane vole, mate promiscuously and are much less social. It turned out that the prairie voles and montane voles have different distributions of oxytocin and vasopressin receptors, Insel and his colleagues discovered.

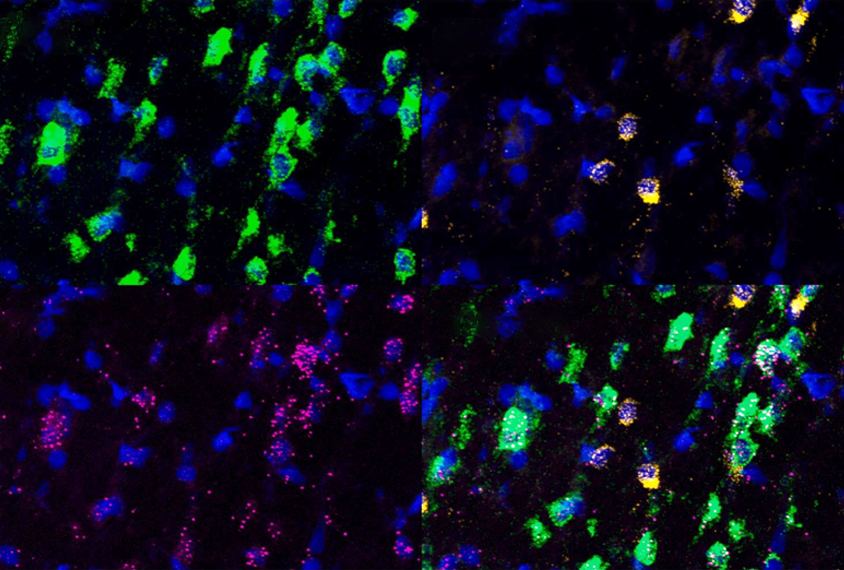

Young began trying to manipulate these behaviors. Adding extra copies of the vasopressin receptor gene into a meadow vole’s ventral pallidum made the normally solitary animal instead seek out companionship, he and his colleagues reported. Knocking out oxytocin receptors resulted in animals with social deficits, they also found.

Young eventually published detailed reviews on the neurobiology of pair bonding and attachment. “Those are seminal works that have stood the test of time,” says Stephanie Preston, professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, who worked with Young at Emory in the mid-1990s.

T

hroughout his time at Emory, Young continued to develop tools to manipulate the oxytocin system across species—work that helped usher in “the more modern era of genetic manipulations” for neuroscience research, says Robert Froemke, professor in New York University’s Neuroscience Institute and otolaryngology department.Using those tools, Young explored how the oxytocin system facilitates pair bonding, parental behavior, fear learning and empathy in different species, and how it affects an animal after the loss of its partner. He also studied how targeting this system could help promote sociability in people with conditions such as autism.

“Part of it is about his ability to understand science from the most basic all the way through to the clinical, and to bring people together around that,” says Adam Guastella, professor of child and youth mental health and a clinical psychologist at the University of Sydney.

That collaborative nature was also evident in how Young approached his own research, says Arjen Boender, a research associate in Young’s lab. He never shied from sharing work out of a fear of being scooped, Boender says.

Young’s ability to reach out to others transcended the bounds of research. He regularly gave public talks about the science behind social relationships; he appeared on science programs on PBS and the BBC; and he even traveled to India to teach neuroscience to Tibetan monks. In 2012, he co-authored a popular science book to explain his work on love and attraction for a lay audience.

In recent years, Young also spoke out against female genital mutilation—and how the practice, in addition to the trauma it inflicts, hinders oxytocin release and pair bonding. That initiative began after he received an email from Reverend Patti Ricotta, who had come across his research, Ricotta recounted in a talk that she gave with him at Emory last year. The “unlikely duo,” as Young put it, ended up organizing conferences in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania to discuss, respectively, the science and theology of partner relationships.

“He was able to translate [his work] into something really practical,” Boender says.

Y

oung relished his rural Georgia roots, according to Phelps, his collaborator and former postdoc. He treated lab visitors to photos of his alligator hunts, made hot sauce from the peppers he grew, and invited his lab members to retreats out on his family farm.“He was very passionate about his work,” Phelps says. “And if his work could lead to some adventure, then even better.”

In his talks on social bonding, Young spoke enthusiastically about the importance of the ties between parents and their babies, and between partners. He included slides with his own wedding pictures—images of him and his wife of 20 years, Anne Murphy, who is professor of neuroscience at Georgia State University, smiling on a beach and dressed in white.