Blocking oxytocin causes birds to sing solitary tunes

Inhibiting the social hormone oxytocin alters the songs male zebra finches sing to attract females.

Blocking the social hormone oxytocin alters the songs male zebra finches sing to attract females.

The findings suggest that oxytocin is involved in language as well as in social behavior. Because oxytocin is linked to autism, it also suggests that the hormone could enhance speech therapy for children with the condition.

Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2018 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, California.

Songbirds such as zebra finches learn their songs much like children learn to speak: by listening to and imitating adults, and by receiving feedback from their parents.

Only male zebra finches sing, and they learn their songs from their fathers. The father birds look at their sons and tap them on the bill to get their attention before launching a song lesson. Just as human mothers change the pitch and cadence of their voice when speaking to an infant — that is, speak in ‘motherese’ — the father birds change the structure of their songs when singing to their sons — essentially a finch ‘fatherese1.’

In the new study, researchers explored how the social context of learning affects zebra finch song. They reared young male zebra finches in cages with a stuffed model of a zebra finch for a ‘father’; the young birds stay in these cages from 30 to 60 days of age.

The team played a two-note song through a speaker for the young birds to learn. “We wanted to have all the birds in the experiment learn the same simple baseline song,” Constantina Theofanopoulou said when presenting the findings. She is a graduate student working with Cedric Boeckx at the University of Barcelona in Spain and Erich Jarvis at Rockefeller University.

Social switch:

When the birds were 60 to 90 days old, the researchers switched them back and forth between two cages: The social cage has a stuffed ‘father,’ a live female finch and a mirror to create the illusion of more birds; the isolation cage has none of those things.

During this phase of the experiment, the birds heard slight variations on their two-note song depending on which cage they were in. They heard a song with a slightly higher-pitched second note in the social cage and one with a slightly lower-pitched second note in the isolation cage, or vice versa.

By 90 days of age, when a zebra finch’s vocal learning is usually complete and his song ‘crystallized,’ five of the six birds had altered their song to match the version they heard in the social cage. (The sixth bird added a third note to his song that matched the social-cage song’s pitch.)

The results suggest that social context shapes the content of what is learned, and not just the speed of learning as previously thought. If language learning works the same way in people, not being tuned in to the social environment may affect speech development in children with autism.

Sad solo:

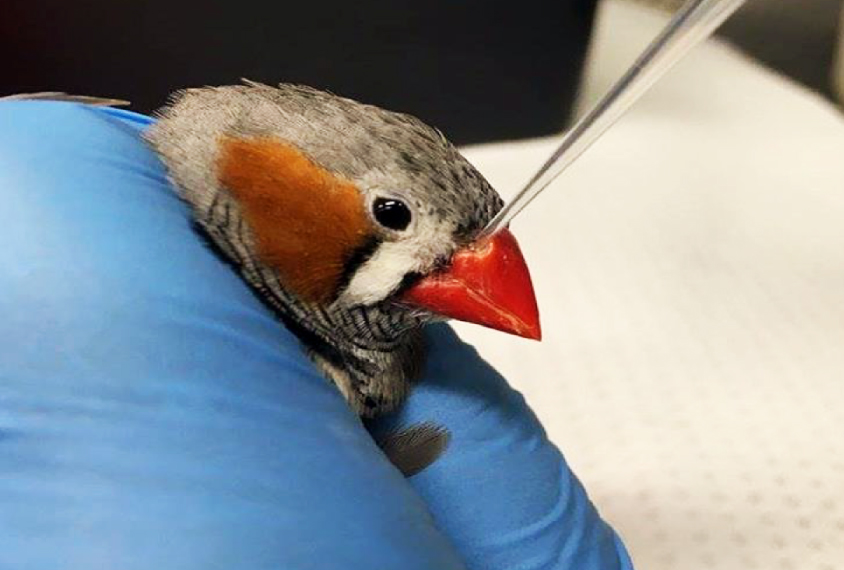

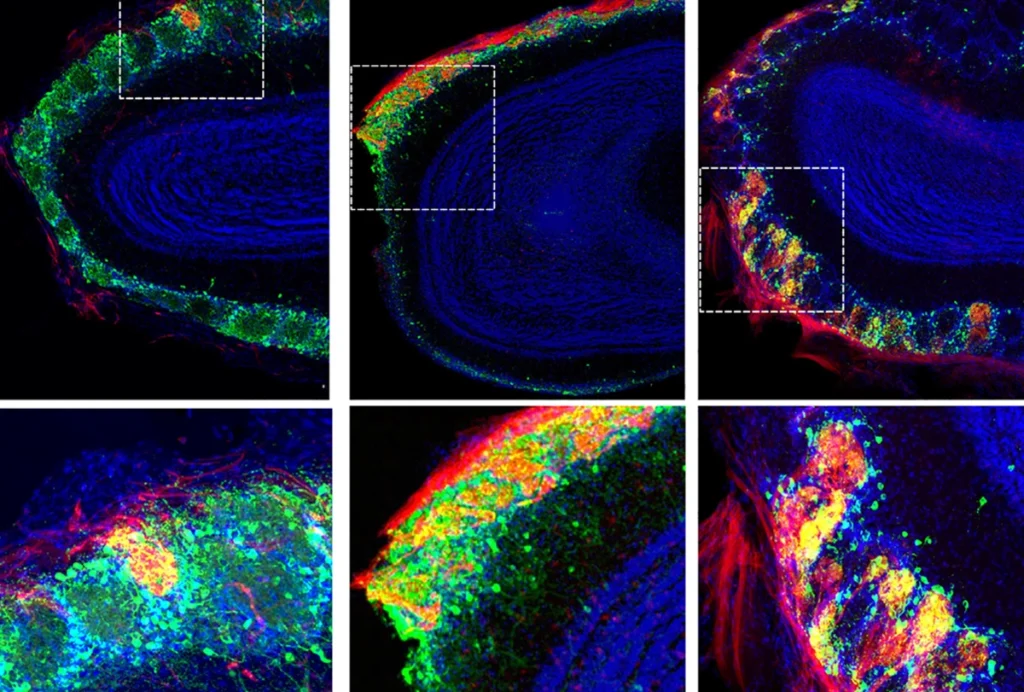

The researchers also investigated whether dampening social reward affects how zebra finches sing. They squirted a compound that blocks oxytocin into the finches’ nostrils. When administered in this way, the oxytocin blocker crosses the blood-brain barrier and reaches the brain, the researchers confirmed.

Male birds typically add preliminary notes to the main motif of their songs to get females to pay attention — as a kind of come-on, Theofanopoulou explains: “I’m singing for you, look at me.”

But a male bird that is treated and then put in a cage with a female zebra finch sings fewer preliminary notes than controls do. The oxytocin blocker turns the male’s romantic serenade into something more like a guy humming to himself.

Some research suggests that an oxytocin nasal spray could help improve social skills in children with autism or make them more responsive to behavioral therapies. The new results suggest that oxytocin could also have a role in speech therapy in autism.

“What I think is that if the social reward, the reinforcement, is enhanced, that this will be a better way for them to get better at speaking,” Theofanopoulou says.

Theofanopoulou has also squirted oxytocin into the nostrils of male zebra finches; so far, this seems to have no effect on the number of preliminary notes in their songs to females.

For more reports from the 2018 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

- Chen Y. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 6641-6646 (2016) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’