Looming large

How many people with autism are also obese?

100407-weight-scale-obese-550×366.jpg

Last month, I wrote about a remarkable study showing a genetic connection between obesity and autism. Rare deletions on chromosome 16, it turns out, crop up in a whopping three percent of individuals who are both obese and have a developmental delay.

This begs the question: How many people with autism are also obese?

There are scant data to address that, but two studies published earlier this year begin to give a rigorous account.

In both, researchers reanalyzed some of the same data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, gathered from phone interviews given in 2003 and 2004 to parents of some 85,000 American children.

The most recent study, published in late February, reports that the rate of obesity in 3- to 17-year-old children with autism is 30.4 percent, significantly higher than the 23.6 percent in healthy controls.

The other report, published in January, only looked in older children, but found roughly the same trend. Looking at data from 47,000 kids aged 10 to 17 years, researchers reported that 23.4 percent of adolescents with autism are obese, compared with 12.2 percent of controls.

Comparing both studies, two important points stand out.

First, the rate of childhood obesity in both groups is much higher in the recent study, which only included children younger than 10. That’s probably a reflection of the growing obesity epidemic.

Second, it seems that the difference between the autism and control groups is more striking in older children and teenagers. This meshes nicely with the genetic study on chromosome 16, which found that the association between obesity and developmental delay is strongest in late adolescence or adulthood.

There are a couple of methodological problems with the studies’ design, however. For instance, they did not define autism using a standardized test, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, or ADOS, but rather as something that any ‘health professional’ once diagnosed.

Still, all evidence to date suggests that kids with autism have an increased risk of being overweight, and will probably prompt some labs to figure out a biological explanation. In the meantime, clinicians should counsel patients with autism about healthy food and exercise.

Explore more from The Transmitter

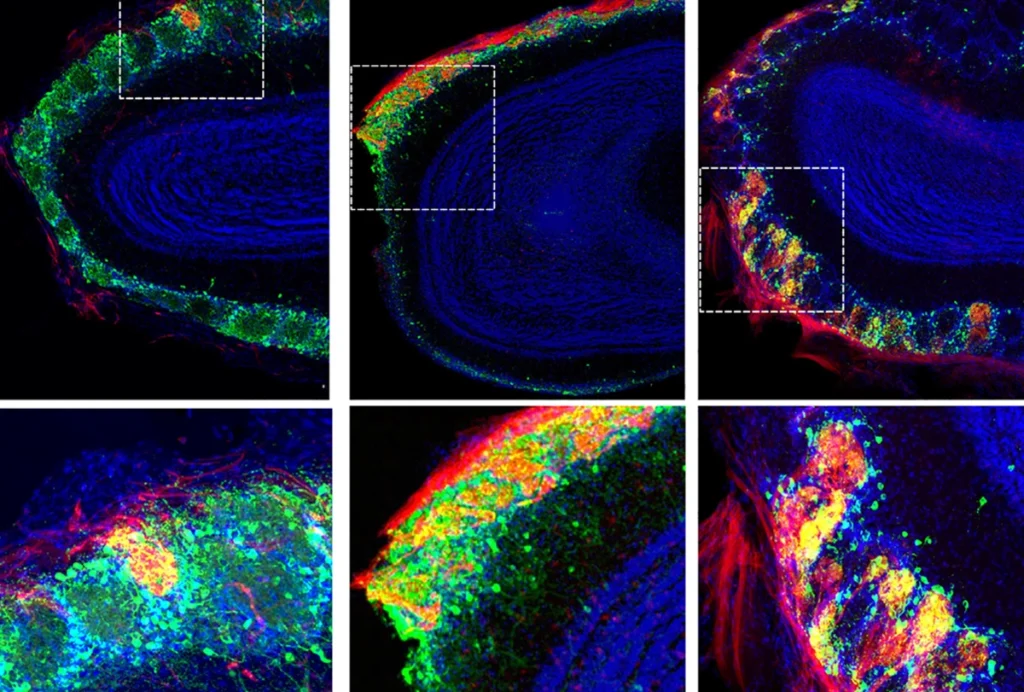

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’