New mouse model mimics many symptoms of autism

Mice lacking the autism-linked gene CNTNAP2 show many of the behaviors associated with the disorder, and exhibit brain circuit disruptions similar to those seen in people who carry mutations in the gene.

Mice lacking the autism-related gene CNTNAP2 also show brain circuit disruptions similar to those seen in people who carry mutations in the gene, the study found.

What’s more, risperidone, a drug often used to treat the symptoms of autism, ameliorates some behaviors, including hyperactivity and repetitive behavior, in these mice.

The researchers presented an early look at the behavioral findings at the 2011 International Meeting for Autism Research.

The study is clearly a landmark in autism research and cause for optimism, says Nicholas Gaiano, associate professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, who was not involved with the work.

“Not only does the work further cement a role for CNTNAP2 in autism biology from a behavioral standpoint, but it provides a beautiful example of how disruption of an [autism]-associated gene can profoundly disrupt brain development,” Gaiano says.

Mutations in CNTNAP2 are associated with a higher risk of autism2,3. People who have inheritedmutations in both copies of the gene have a rare disorder called cortical dysplasia-focal epilepsy syndrome, or CDFE. The syndrome is characterized by epileptic seizures, loss of language, intellectual disability and, in some 70 percent of cases, autism.

Some genetic variants of CNTNAP2 are also associated with specific language impairment, a disorder not accompanied by intellectual disability, autism or physical problems such as hearing loss.

The faithfulness with which the new model recapitulates many of the features of autism came as a surprise to the investigators.

“I thought it would be a great system for studying how this gene affects neural development,” says lead investigator Daniel Geschwind, chair of human genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine.

The mice offer that and much more: They are hyperactive, have social and vocal communication deficits and repetitive behavior, all hallmarks of autism.

“I’ve been somewhat conservative about making parallels between human behavior and mouse behavior,” says Geschwind. “I’m much more optimistic about using mice after seeing this.”

Signaling imbalance:

Like people with CDFE, mice lacking both copies of CNTNAP2 develop seizures. The mutants also have fewer interneurons — a subtype of neurons that dampen electrical signaling in the brain.

Specifically, the mice have fewer neurons that produce a signaling molecule called gamma-aminobutyric acid or GABA, which slows down neural activity. This suggests that the loss of CNTNAP2 disrupts the balance between excitatory and inhibitory signaling in the brain.

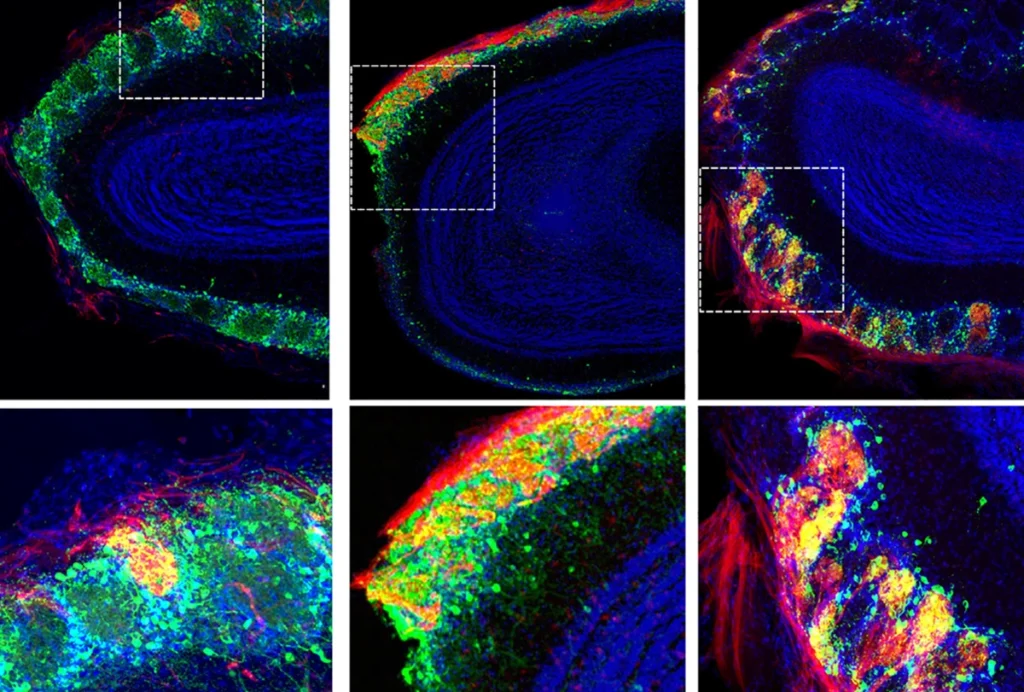

The brains of the mutant mice also reveal aberrations in neuronal migration: Rather than traveling to their proper destinations, neurons cluster in clumps or rows in the deep layers of the cortex. About 43 percent of individuals with CDFE show visible evidence of these defects on magnetic resonance imaging scans, Geschwind says.

The defects in interneurons and in neuronal migration may underlie the circuit abnormalities seen in the animals, Geschwind says. But it’s not yet clear whether these defects are caused by the same molecular mechanism, or occur independently of each other.

In either case, the end result is lack of synchrony in signaling through synapses, the junctions between neurons, in the mutant animals. This defect may affect a diverse set of pathways, leading to the range of behavioral symptoms seen in the animals.

“The real power of this analysis is that [Geschwind] has not just looked at the cellular and synaptic level, but begun to point out how broad pathways are affected,” says Gordon Fishell, professor of developmental genetics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center.

The emerging picture is not just a snapshot, Fishell says. “It’s a landscape that offers a holistic picture of how autism is manifested at a biochemical level in the brain.”

The new findings build on five years of investigation, which began when Brett Abrahams, a former postdoctoral fellow in Geschwind’s lab, used microarrays to analyze gene expression in human fetal brains.

That work identified CNTNAP2 as a gene that showed a peculiar pattern of enrichment in the prefrontal cortex that wasn’t seen in mice or rats, says Abrahams, now assistant professor of genetics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City.

At first, the researchers linked variants in the gene with language, but not with autism.

Israeli researcher Elior Peles developed the mutant mice and carried out studies of the peripheral nervous system in the mice.

In 2010,a functional magnetic resonance imaging study led by Geschwind’s lab showed that unaffected children who carry a common variant of CNTNAP2 show the same aberrant pattern of brain connectivity as do children with autism4.

“It’s a really nice story from the laboratory research perspective,” says Geschwind. “It shows how convergent approaches point you in the right direction.”

The new model also holds promise for developing treatments for autism. Risperidone ameliorates some autism-associated behaviors in the animals, but it has no effect on their social deficits. It is likely that two or three drugs combined with behavior therapy will be necessary to treat the disorder, Geschwind says.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’