Sensitive new test may help researchers evaluate treatments

A new tool may be more useful than the current gold standard for assessing whether an autism treatment improves social communication.

A new tool may be more useful than the current gold standard for assessing whether an autism treatment improves social communication, suggest two studies presented Thursday at the 2016 International Meeting for Autism Research in Baltimore.

Most behavioral treatments for autism aim to ease problems with social communication, one of the core features of the condition. But most research measures are not sensitive enough to detect subtle changes in these skills. Some tools require extensive expertise and training to use, and others rely on reports from parents, whose responses can be swayed by a placebo effect or the desire to see their child improve.

Catherine Lord and her colleagues have developed a new tool, called the Brief Observation of Social Communication Change (BOSCC), that they say is simple and reliable. The test is designed to measure social communication behaviors in toddlers and preschool-aged children as they play with an adult, and requires little training to administer.

It consists of 15 items that probe the frequency and quality of a child’s social communication behaviors, such as eye contact, facial expressions and vocalizations, as well as their restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. The tool is based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), a gold-standard tool for diagnosing autism, which Lord co-developed in the 1980s.

BOSCC scores each item on a scale from 0 to 5, rather than the narrower range of 0 to 2 used on the ADOS — a change that makes it sensitive to subtle changes in behavior, the researchers say.

Reliable test:

Lord’s team used BOSCC to assess social communication abilities in 56 children with autism as they received behavioral therapy. The researchers periodically recorded videos of the children playing with their parents over an average period of six months.

A separate set of researchers who were unaware of the child’s treatment status then watched the videos and scored the children’s performance on both the BOSCC and ADOS. They also measured the children’s language and communication skills using other standardized tests.

The team found two lines of evidence that the BOSCC ratings are reliable. Different researchers tended to arrive at the same BOSCC and ADOS scores for a given video. And a given rater tended to give consistent scores to videos from the same child over a one-month period, suggesting the test’s reliability.

After receiving treatment for six months, the children improved as a group by an average of four points on the BOSCC, a statistically significant indication of improvement, but did not show significant improvement on the ADOS. Children who improved on the BOSCC also fared better on the other standardized tests, suggesting that the new tool detects real progress in social communication.

“This gives us some initial evidence that perhaps some of the change that we’re observing on the BOSCC may actually be meaningful,” says Rebecca Grzadzinski, a graduate student in Lord’s lab who presented the findings. The team published the findings in April in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders1.

Double take:

In the second study, researchers in the Netherlands evaluated the BOSCC using videos of 44 toddlers with autism playing with their parents. They took the videos before the children received treatment and again one year later. They also compared the tool’s ability to detect change in social communication with that of the ADOS.

Overall, they saw similar improvements on both tools across the group. But differences emerged when the researchers compared each child’s scores on the tools.

Using the BOSCC, the researchers found that 20.5 percent of the children showed reliable improvements in social communication, and 9.1 percent became worse. When the researchers used the ADOS, however, they found that 11.4 percent improved and none of the children worsened.

“At an individual level, the BOSCC seems to be better able to capture subtle individual changes,” says Mirjam Pijl, a graduate student in Jan Buitelaar’s lab at the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre in the Netherlands, who presented the unpublished findings. “More research is needed, but we do think it is a promising measure.”

For more reports from the 2016 International Meeting for Autism Research, please click here.

- Grzadzinski R. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2016) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

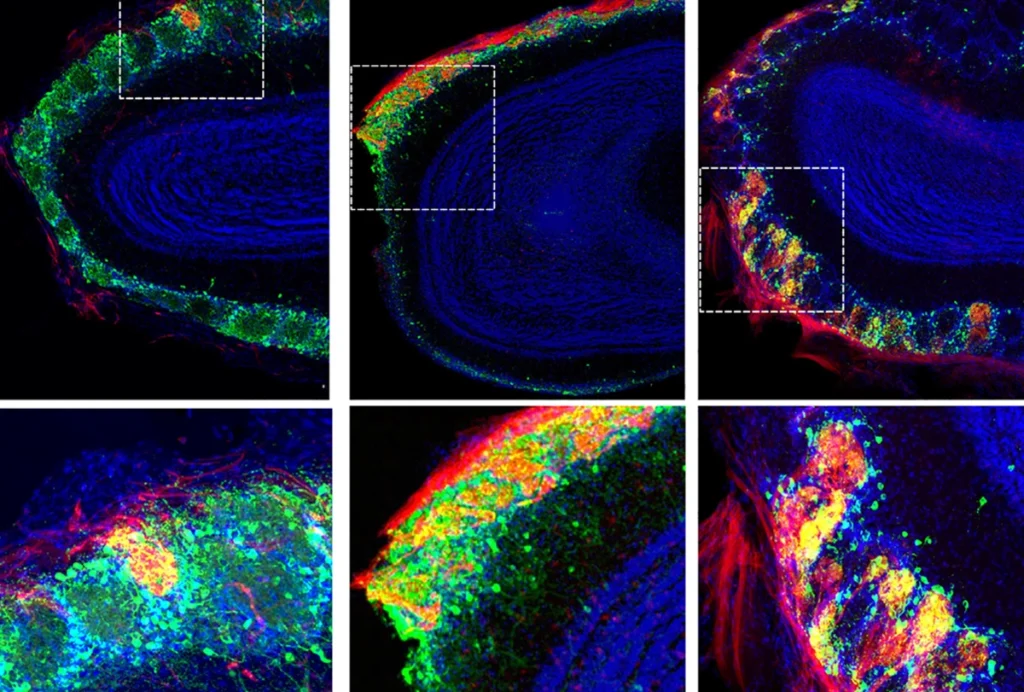

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’