Sensory sensitivity may share genetic roots with autism

The heritable factors that underlie autism may overlap with those that influence unusual sensory responses.

The heritable factors that underlie autism significantly overlap with those that influence unusual sensory responses, a new study of more than 12,000 twin pairs suggests1.

The findings reinforce the idea that sensory sensitivities are a core feature of autism. They also hint that a better understanding of the genetic factors underlying sensory responses could reveal insights into autism.

Still, experts caution that the link is preliminary because the study focused on only one form of sensory sensitivity.

Up to 90 percent of people with autism are either overly sensitive to sound, sight, taste, smell or touch, or barely notice them at all. Some seek out sensations by, for example, spinning in circles or stroking items with particular textures. Since 2013, the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” has included sensory sensitivities in the list of diagnostic criteria for autism.

The reason for a link between autism and these sensitivities has been unclear. Parents and siblings of people with autism often have milder versions of these features, hinting that the sensitivities may run in families.

“You can’t really say whether an association you see is genetic or environmental from a family study, so we thought that [a twin study] could be an informative approach,” says Mark Taylor, a postdoctoral fellow in the medical epidemiology and biostatistics department at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden. (Paul Lichtenstein and Sebastian Lundström, the two investigators who supervised the work, were both unavailable for comment.)

The new work suggests that about 85 percent of the overlap between autism features and sensory sensitivities can be explained by shared genetic factors.

“I think that this study is important and well conducted,” says Elise Robinson, assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard University, who was not involved in the study. “There’s been this clinical link between autism and sensory issues for a very long time, but a genetic link hasn’t been clearly established between those two things.”

Family factors:

Taylor and his colleagues analyzed data on autism traits and sensory sensitivities in 3,586 pairs of identical twins and 8,833 pairs of fraternal twins. The data came from the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden, which follows the development of all twins born in Sweden since 1992.

When the children were 9 or 12 years old, their parents completed a 96-item questionnaire, including 17 items about autism traits and 5 about sensory hypersensitivity. The questions are based on the diagnostic criteria for autism and other conditions.

An analysis of the responses revealed that when one twin in a pair has autism features, the other often has sensory sensitivities; this link is stronger among identical twins than fraternal ones. Because identical twins share all of their genetic material and fraternal twins only about half, the finding suggests that traits related to autism and sensory sensitivity share a genetic basis. The results hold up when the researchers control for the children’s sex and age.

By comparing the difference between the scores of identical and fraternal twin pairs, the researchers estimate that genetic factors account for 84 percent of the overlap in traits in girls, and 89 percent in boys. The findings were published 5 December in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Crude measure:

However, several experts caution against overinterpreting the results.

The researchers performed “a pretty reasonable appraisal of autistic traits,” says John Constantino, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study. Still, the assessment of sensory sensitivities is rather crude and limited, he says: The questions probe only sensory hypersensitivity, and not under-reactivity or sensory-seeking behaviors.

Other researchers — including those involved in the study — agree with this criticism.

“It’s five questions about whether or not the person responds to or perceives different sensations differently than other people,” says Anne Kirby, assistant professor of occupational and recreational therapies at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, who was not involved in the study. “In behavioral studies, we use measures that have many more questions, and separate out different types of sensory responses.”

However, sensory behaviors are difficult to assess in depth with a large group of participants, says Grace Baranek, associate dean and chair of occupational science and occupational therapy at the University of Southern California, who was not involved in the study. The latest work should spur more researchers to study sensory issues in autism, “an area that has been so understudied,” she says. “A lot of people are really paying more attention to it now.”

In the meantime, Taylor and his colleagues are exploring whether sensory sensitivities share genetic factors with other conditions that commonly occur in people with autism, such as anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

- Taylor M. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2018) Abstract

This article has been modified from the original. Grace Baranek is at the University of Southern California, not the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as previously stated.

Explore more from The Transmitter

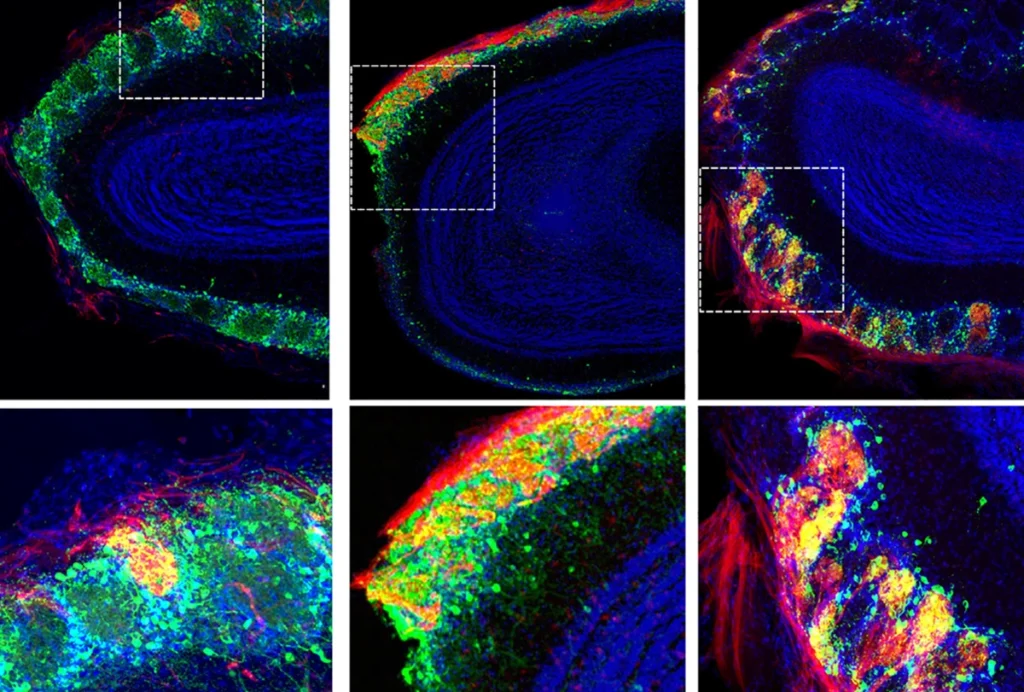

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’