As neuroscientists, Florian Engert and Bence Ölveczky are always looking for ways to tackle new challenges. Later this month, the pair — who have been friends for two decades — are booked to bring that same ambition to the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race. On 15 November, they plan to join a crew of other amateur sailors on board a 70-foot yacht, racing from Cape Town, South Africa, to Freemantle, Australia. That leg of the race, one of eight in total, passes through some of the world’s most dangerous waters, a stretch of the Southern Ocean known for its 30-foot swells and steady gale-force winds.

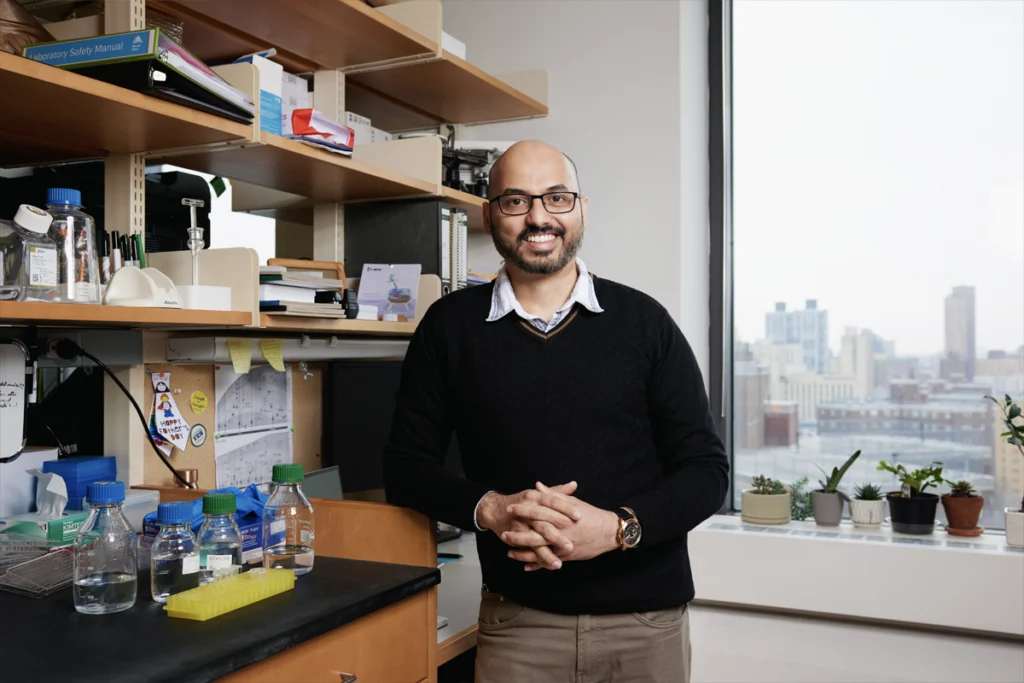

Engert, professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, explores how changes in neuronal activity reflect variations in behavior in zebrafish and other organisms. A mechanical engineer by training, Ölveczky is now professor of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard, where he studies how rats learn and execute motor skills.

The sailor-scientists completed organized training for the race over the summer and sat down with The Transmitter in October to discuss sleeping and cooking on the high seas, as well as their annual lab retreats and volleyball rivalry. Check out the crew diaries to follow Engert and Ölveczky’s progress as part of team “Washington, D.C.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Spectrum: Why this race?

Bence Ölveczky: I’ve sailed for much of my life. My father was a national champion in a variety of different sail groups and was a professional sailor trainer for the Tokyo Olympics. So I’ve been in a boat since I was 2 years old. I just love it.

The leg we’re going on in November holds a particular fascination for me — it is the white whale for sailors. It’s the one that must be conquered. It’s the ocean that fewest people have crossed. And that’s for good reason, you know? And so I decided, we have to do this. And I got this guy on board.

Florian Engert: I would never have done this without Bencie. I think what got me was when he told me this is the track where you get the biggest waves and the strongest winds on the planet. And I found that very appealing.