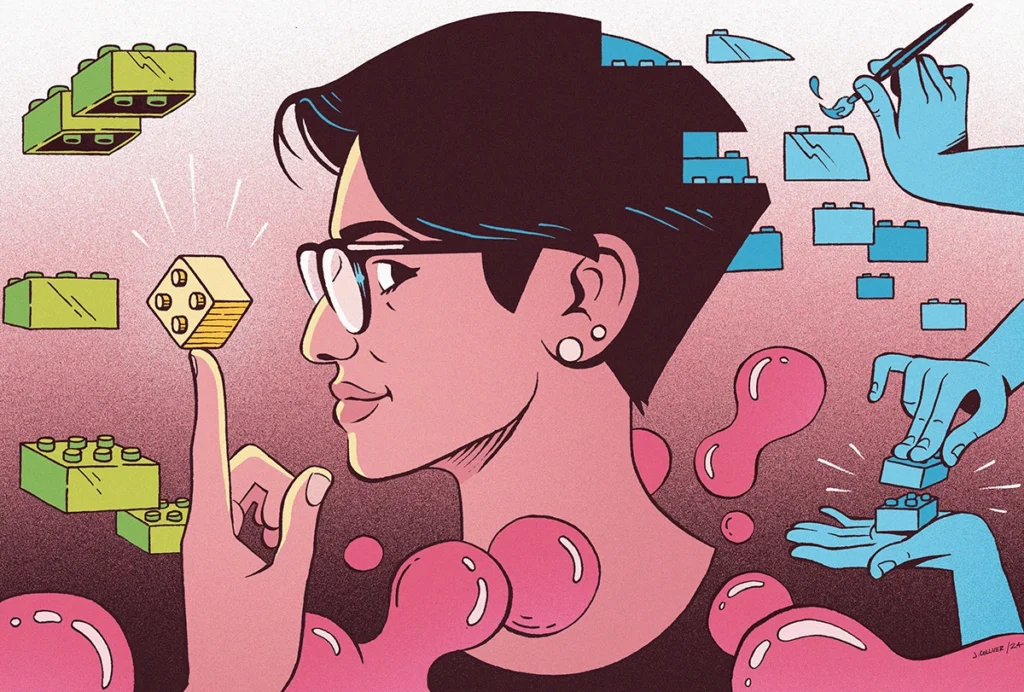

Tessa Montague’s first attempt at studying cuttlefish camouflage is forever etched into her memory — and her clothes.

She was about to start her postdoctoral fellowship in Richard Axel’s lab at Columbia University. She had just built her first tank, an opaque plastic tub with a glass window on the bottom. She planned to place various patterns under the glass to explore how dwarf cuttlefish, Sepia bandensis, can mirror those designs on their mottled skin.

But as soon as one of the credit-card-sized cephalopods swam over the glass, it shot out of the tank — possibly alarmed by its reflection, Montague says — spraying her head to toe with its jet-black ink before it plopped onto the floor.

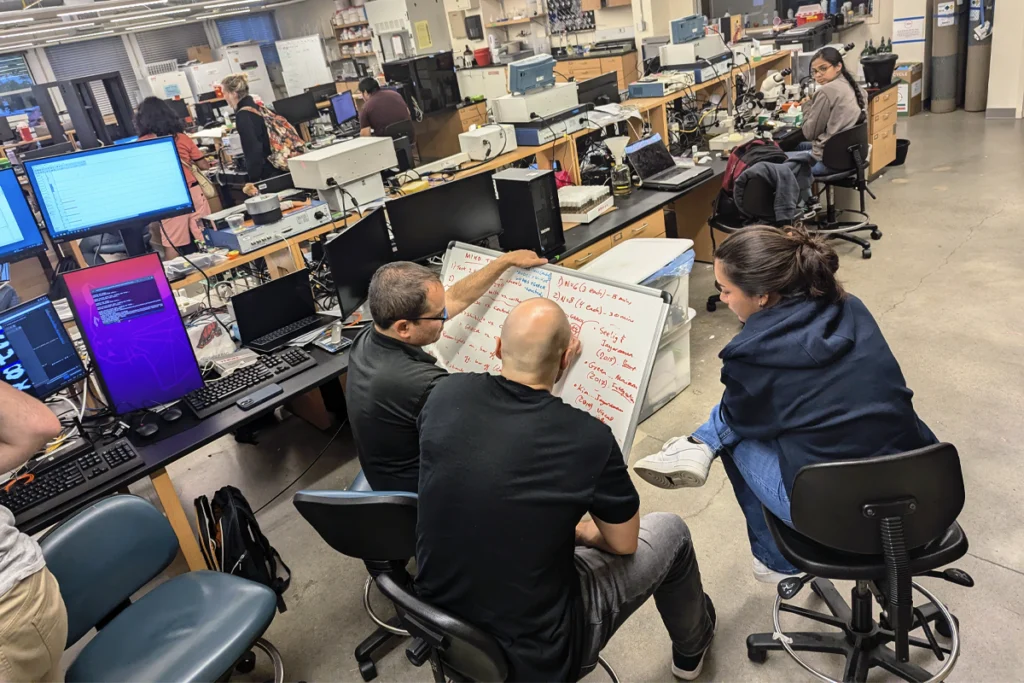

Montague’s subsequent experiments have been decidedly less murky. Since that inaugural inking incident, she and her colleagues have established a cuttlefish breeding program, sequenced the organism’s genome and transcriptome, described its stages of embryonic development and created 3D maps of its brain and internal organs. They have developed a digital tank to test camouflage in a form of virtual reality and are engineering transgenic lines and adapting existing miniature microscopes for use underwater to explore how cuttlefish conjure up their deft disguises.

Outside her own laboratory confines, Montague helps to facilitate other transformations: She teaches undergraduate neuroscience courses at local correctional facilities, runs biology workshops for high-school students in Ghana, and mentored a student in the United Arab Emirates who launched a DNA experiment into space.

“I’m a big believer in the power of education, and that people should have second chances,” Montague says.

The Transmitter spoke with Montague about her work to decipher cuttlefish camouflage, her various educational efforts, and how she contemplated a career as a CIA agent.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: What “big question” drives your research?

Tessa Montague: I’m interested in how the brain creates an internal representation of the visual world. Cephalopods recreate their surroundings on their skin during camouflaging, by changing the color, pattern and texture of their skin. Their skin display is controlled by motor neurons projecting from their brain. So their skin creates a manifestation of the neural activity in their brain, and it shows us the animal’s visual perception of the external world. We’re using this camouflaging behavior to tease apart how the physical world is represented in the brain.

The most exciting part of the project is that it requires the intersection of so many disciplines. Our team includes an artist, an aquatics expert, a computer scientist, an imaging specialist, a neuroscientist and me, a molecular biologist. We need all this expertise to understand cuttlefish at the ecological, neurological, behavioral and molecular level. I love this melting pot.