Infant gaze signals autism risk, study suggests

At 6 months of age, siblings of children with autism are less likely to gaze spontaneously at their caregivers while focused on learning a new task, though they learn the task just as quickly as do low-risk infants, according to a study in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

Object lessons: Infant siblings of children with autism tend to ignore their mothers when mastering a new skill.

At 6 months of age, siblings of children with autism are less likely to spontaneously gaze at their caregivers while focused on learning a new task, though they learn the task just as quickly as do low-risk infants, according to a study published this month in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry1.

Younger siblings of children with autism are up to 20 times as likely to develop the disorder as children without a family history2.

Previous studies have shown that, at 12 to 14 months of age, siblings of children with autism make fewer attempts to spontaneously engage the attention of their caregivers3. The new study shows that these high-risk siblings may already lag behind their peers at the half-year mark, potentially providing an early behavioral marker of autism risk.

“These findings are very exciting, especially as they have gotten results as early as 6 months of age,” says Tricia Striano, research clinician at the Hunter College Autism Center in New York City, who was not involved in the research.

In the study, 25 infants with no family history of autism and 25 infants with older siblings diagnosed with autism sat in a specially designed chair for ten minutes, with a musical toy to their right and their primary caregiver — usually their mother — to the left. Each chair is equipped with a joystick that controls a music and light display on the toy.

The researchers tracked the number of times the babies directed their gaze to caregivers, both when caregivers were passive observers and when they actively attempted to engage their child’s attention.

When involved in an interesting new task, healthy infants typically look toward their caregivers as if inviting them to share in the fun — even when that person is not actively engaged with them.

Siblings of children with autism learn to operate the toy just as readily as the healthy infants. “What they didn’t do was initiate looks at their moms,” says lead researcher Rebecca Landa, director of the Center for Autism and Related Disorders at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore.

Instead, their gaze remains fixed on the toy until their mothers start to speak to them. At that point, they respond just as readily as the controls, Landa says.

The subtlety of this distinction may have caused other researchers to miss it in studies of younger infants, she says. “We developed this challenging task that gave them the opportunity to initiate engagement as well as respond to it.”

Tough task:

Impairments in joint attention — sharing one’s experience of an object or event by gazing or pointing — are one of the earliest signs of autism.

Striano says it is difficult to measure joint attention in babies younger than 1 year old. Most researchers previously assumed that joint attention begins to develop at around 9 months of age — but that may just be because babies at that age typically develop a wider repertoire of actions and gestures to capture attention.

“Six-month-old babies can’t talk, walk or gesture yet so they don’t have many means of initiating social engagement,” Landa says. The task developed by her lab shows the underpinnings of joint attention and the seeming vulnerability of the infant siblings of children with autism in this area.

Landa plans to conduct follow-up studies with children at 14, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months.

She cautions that the task is not in itself a definitive marker for autism. “Some babies will look fine on this measure but go on to [develop] autism while others won’t do well but may be fine,” she says. “In one month, infants this age make a lot of strides.”

Sally Ozonoff, professor-in-residence in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, applauds both the results and Landa’s prudence.

“I have a very positive impression of the excellent work that this lab is doing. I just urge caution about identifying this as an early marker until after we know which children develop autism spectrum disorders,” Ozonoff says.

In a commentary accompanying the article in the journal4, Ozonoff points to her own experience as a reason for exercising caution.

In a 2007 paper, she and her colleagues reported that 6-month-old infants who have older siblings with autism focus almost exclusively on their mothers’ mouths. In contrast, healthy infants tend to direct their gaze to their mothers’ eyes5.

Based on these observations, Ozonoff says, she and colleagues were sure they had found an early marker for autism. They were dismayed when they later found that none of the 11 children who focused on their mothers’ mouths developed autism, but 3 other infants, who followed the typical pattern of looking at the mother’s eyes, did6.

“It was an important reminder that not every hypothesis with intuitive appeal and face validity is actually right,” Ozonoff says.

References:

-

Bhat A.N. et al. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 51, 989-997 (2010) PubMed

-

Zwaigenbaum L. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 466-480 (2006) PubMed

-

Rogers S.J. Autism Res. 2, 125-137 (2009) Abstract

-

Ozonoff S. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 51, 965-966 (2010) PubMed

-

Merin N. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 108-121 (2007) PubMed

-

Young G.S. Dev. Sci. 12, 798-814 (2009) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

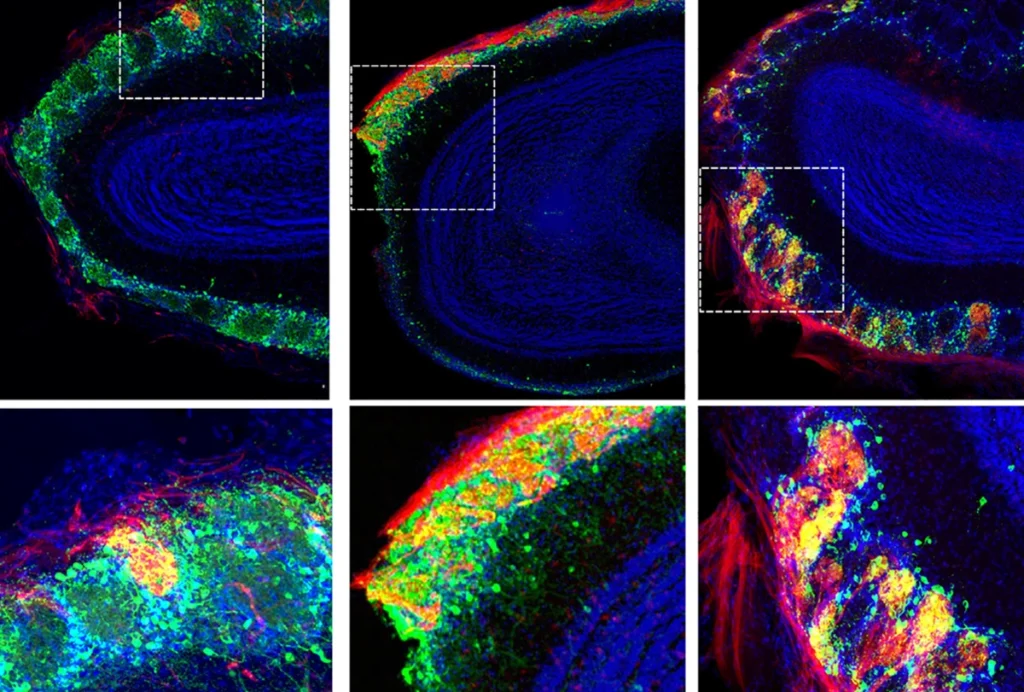

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’