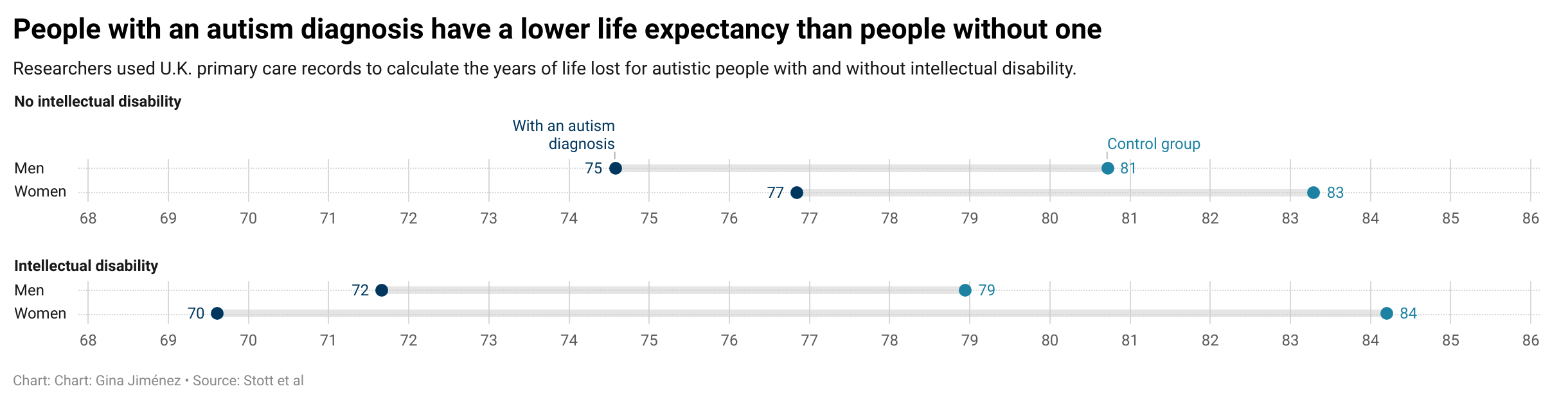

Autistic people without intellectual disability live about six years less, on average, than non-autistic people do, according to a study in the United Kingdom.

The findings confirm past research linking autism to early death but suggest that the life expectancy gap may be smaller than previously thought.

“The reason we wanted to look at life expectancy was that there is a widely quoted statistic that autistic people live 16 years less on average, which was quite frightening,” says lead investigator Joshua Stott, professor of aging and clinical psychology at University College London.

That statistic comes from a 2018 Swedish study that compared the average age at death for more than 27,000 autistic people and 2.6 million gender- and age-matched non-autistic people, using data from the country’s National Patient Register and Cause of Death Register. But that approach may have underestimated autistic people’s lifespan, because many elderly adults are undiagnosed, Stott says.

Instead, he and his colleagues used electronic primary care health records from January 1989 to January 2019 to identify 17,130 thousand autistic adults without intellectual disability and 6,450 autistic adults with intellectual disability. They matched each autistic person with 10 non-autistic people of the same age and sex, and with comparable intellectual abilities, from the same primary care practice. They then estimated overall life expectancy at age 18, based on mortality rates they calculated for both biological sexes across every single year of age.