On a snowy day in December 2022, Coraline Vazquez spent the morning playing with her parents, Dani and Gabe. In pajamas and sweatpants, the trio snuggled together on the floor in Coraline’s cozy bedroom in the family home in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, a town of about 4,000 people an hour and a half northwest of Philadelphia. On a small table, a cellphone was propped up, its camera aimed at Coraline as the 2-year-old turned her attention to a pile of large plastic blocks spilled across the rug. One by one, she picked them up and placed them next to each other in a line.

“You don’t want to stack them?” Dani, 22, asked.

Gabe, 24, demonstrated by picking up a block and putting it on top of another. When he held a block out to her, Coraline added it to the tower they were building. Then she took another one from him.

“Thank you,” Coraline said.

“Thank you,” Dani echoed.

For about half an hour, they vroomed toy cars across a play mat and played tickle monster and catch.

Kaitlin McHenry’s voice came through the phone. “Do you have bubbles?” she asked.

Dani produced a green plastic jar.

“One, two … blow!” cried Gabe, blowing a string of pearly bubbles into the air.

A bubble floated toward the window, and Coraline raced after it. “Bubbles!” she yelled.

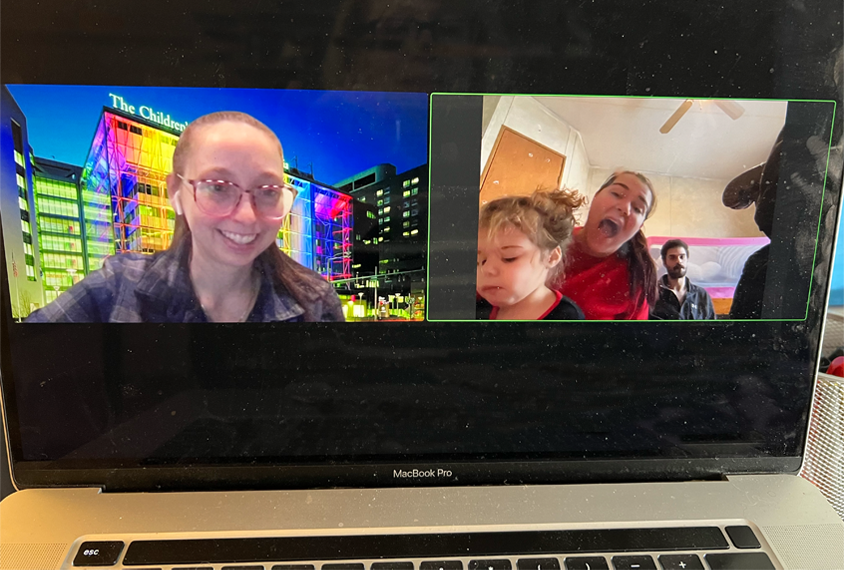

In many ways, it was typical family hangout time. But not entirely. McHenry is a nurse practitioner at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), and she was trying to determine if Coraline has autism, something the Vazquezes had been worried about for months. To help with this, Dani occasionally picked up the phone and followed Coraline as the little girl darted into the corner to look for a toy or climbed into the pile of pillows on her bed — whatever angle might help McHenry, who had asked to see Coraline’s face and eyes as much as possible, even when Dani and Gabe were answering questions about Coraline’s medical and developmental history.

At one point, McHenry heard a happy little scream and asked about it. She also asked about behavior and language skills, eye contact, gestures, play habits and interactions with other children.

“You said following directions is hard,” she said. “If you said, ‘Coraline, go get your shoes,’ would she do it?”

“No.”

“What if you pointed?”

“Not really.”

When Gabe and Coraline were stacking blocks, McHenry asked Gabe to delay handing over a block so that Coraline would have to ask for it. Block in hand, he pretended to look the other way. Instead of asking, Coraline grabbed his hand and pulled it toward her. And when Gabe started blowing bubbles, McHenry wanted to see if Coraline would ask her father to blow more. Coraline did ask, sort of — “I love you! Bubbles!” she cried. But first, she tried touching her father’s hand.

Picking up a parent’s hand and moving it to a car, a block, or the wand from the bubble jar is not typical of children her age. “We call it using the hand as a tool,” McHenry says.