Wide awake: Why children with autism struggle with sleep

Half of children who have autism have trouble falling or staying asleep, which may make their symptoms worse. Scientists are just beginning to explore what goes wrong in the midnight hour.

B

ramli was giving the stink eye to the grown-ups in her room, shooting resentful glances their way. Around 7:30 p.m. on a warm June evening, daylight was fading outside her home in Morgan Hill, California. A 5-year-old with curly brown hair, Bramli was dressed in pink-and-green pajamas and rigged from head to toe with more than 20 sensors. Crowning her head was a snug black spandex cap studded with electrodes connected to black wires that bunched together and ran down her back.The girl was about to undergo an evaluation that would track her brainwaves, eye movements, heart, muscle activity and breathing as she slept. But Bramli, who has severe autism and is nonverbal, is an energetic, trampoline-loving whirlwind who doesn’t often sit still for long. Just putting all the monitoring equipment on her was no small feat.

Bramli wriggled, whimpered, moaned and sobbed as two Stanford University researchers gently cajoled her through the hook-up process. The girl’s mother, Haley Bennett, went all out to distract her with treats that were normally off limits after dinner: lollipops, soda and play time on the Nintendo and mini iPad.

Eventually, the girl quieted, sulking on her bed as she watched YouTube music videos. “None of us like to have our children be uncomfortable for any reason,” Bennett says. “But at the same time, when you’re looking at a life of never sleeping, day in and day out, it’s worth it in the end.”

It was worth it to Bennett and her husband if it could possibly bring some peace to their evenings. Their brood of four includes Bramli and 7-year-old Ryker, who also has autism. Each night, it takes hours for the two to fall asleep. Bramli, for example, often gets out of bed and climbs about in her closet, and her parents have to tuck her back in six or eight times before she finally goes down sometime between 10:30 p.m. and midnight.

With sleep disturbances afflicting at least half of children with autism, such bedtime horror stories are common in households such as the Bennetts’. “It’s very, very disruptive to the family,” says Ruth O’Hara, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at Stanford University in California.

Bramli’s overnight assessment is part of a study that O’Hara is leading to understand why so many of these children have so much trouble sleeping. Sleep deprivation isn’t merely unpleasant, O’Hara points out: Increasingly, researchers are recognizing that sleep is critical for brain development and health. “Sleep disturbance impacts cognition, it impacts mood, and it impacts behavior,” she says — domains that are also affected by autism. By improving sleep, symptoms in these areas may also improve.

It’s unclear exactly why or how sleep is derailed more often in people with autism than in the general population, but a few theories have begun to emerge. One school of thought blames malfunctions in the body’s 24-hour biological ‘clock’ — called the circadian rhythm — perhaps due to dysregulation of the hormone melatonin, which is involved in controlling the sleep-wake cycle. Poor slumber is known to arise from any number of other causes, too: medication side effects, too much stimulation at bedtime or medical disorders ranging from anxiety and epilepsy to restless legs syndrome and gastrointestinal problems. O’Hara’s work suggests that problems with breathing during sleep could also be the culprit in many cases.

This nascent body of research hasn’t yet coalesced into a coherent picture of why sleep is such a struggle in autism, but some studies are pointing to a few solutions that may help families like the Bennetts rest a little easier.

”“Sleep disturbance impacts cognition, it impacts mood, and it impacts behavior.” Stanford University psychologist Ruth O’Hara.

Wide awake:

S

leep troubles have long taken a back seat in autism studies, not least because doctors and parents have their hands full addressing other pressing priorities. As a result, just about all anyone can say with certainty is that sleep problems are rife among people with autism, and that it’s a complicated biological puzzle to solve.In the 1990s, Australian psychologist Amanda Richdale found that 44 to 83 percent of children on the spectrum have some kind of difficulty with slumber, based on parent reports. Since then, a growing number of studies using increasingly sophisticated objective methods — including video recordings and FitBit-like wristwatches that track movements during sleep — have confirmed the high prevalence of sleep disruptions in this population.

What they’ve found is that children on the spectrum most commonly struggle with insomnia that delays the onset of sleep. They also get less rest overall than do typically developing children, and frequently awaken during the wee hours, roiling the household. “I still remember the mother of a 19-year-old telling me that her daughter would wake for long periods of time at night, just lying in bed singing to herself,” says Richdale, associate professor of psychology at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia.

Also now evident is that sleepless nights can take a toll on autism symptoms. “Children with autism who have compromised sleep are at greater risk for poor daytime behavior,” Richdale says. Poor sleep exacerbates some of the classic difficulties of autism, such as being easily excitable, prone to repetitive behaviors and having trouble with social interactions, communication and attention. Chronic lack of shut-eye can intensify stress and anxiety in fatigued mothers and fathers, too, which may in turn affect their parenting and interactions with their children.

More recently, an intriguing finding that children with autism might have less rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep has added to general concerns that a lack of proper slumber may worsen cognitive functioning in people with the disorder. The REM phase, when most dreaming occurs, is thought to be key for memory and learning. Other scientists have begun exploring factors that might cause individuals on the spectrum to stay awake, ranging from psychological issues such as anxiety to a core neurobiological dysfunction in the circadian rhythm.

For the Bennett household, the cycle of sleeplessness and stress is all too familiar. Bramli “has dark circles under her eyes all the time,” says her weary mother, who herself suffers when her children can’t sleep. Bennett has had pneumonia three times this year, she says. “I get sick a lot more than I used to, just because I’m run-down.”

When Bramli first underwent testing in the Stanford study in October 2014, the researchers found one cause of her troubles: sleep apnea, a condition in which breathing repeatedly stops for seconds at a time throughout the night, triggering unconscious ‘micro-arousals’ as the sleeper briefly gasps awake. The breathing disruptions can result from a physical blockage of the upper airway by soft tissues, such as the tonsils and adenoids, or from a brain glitch. Partial airway closures can also cause shallow breathing, or hypopnea, which also can interrupt sleep.

According to the data, Bramli had 15 hypopnea and apnea episodes and 63 micro-arousals in just one night. Although it’s normal for sleepers to experience some arousals, the girl’s readings raised enough of a red flag for O’Hara to refer her to the Stanford sleep clinic. Bramli later had surgery to remove her tonsils, which made a big difference. The girl has been sleeping more deeply and is able to make it through the days with less crying. She is less manic, with more stable levels of energy, her mother says. But getting her to actually fall asleep is still a challenge, so the research team went back to the family’s home in June to see if any other issues might come to light.

That June night, after plugging all the sensor wires into a small portable computer that would record the data, the researchers left. It wasn’t until nearly three hours later that Bramli finally dropped into solid slumber, sleeping until 7:45 the next morning.

7:16 p.m. Bramli, a nonverbal 5-year-old who has severe autism and chronic insomnia, underwent a sleep assessment at her home as part of a Stanford University study. Around 7 p.m. on a June evening, her mother, Haley Bennett (center), helped researchers patiently coax the child into letting them place more than 20 sensors on her.

7:20 p.m. The noninvasive overnight sleep test, known as polysomnography, monitors the child’s brain and body during sleep. Scalp electrodes embedded in a black cap detect brainwaves, and a gel squirted under each electrode helps conduct the electrical signals.

7:28 p.m. After they moved Bramli to her bed, researcher Isabelle Cotto (right) sneaked two belts around the girl’s torso to monitor her breathing. Throughout the process, Bramli’s mother distracted her with lollipops, sips of soda, Nintendo games and a mini iPad.

7:36 p.m. Bramli watched a music video from “Frozen” as the researchers plugged all the connecting wires from the sensors into a small portable computer device. They would leave the device there overnight.

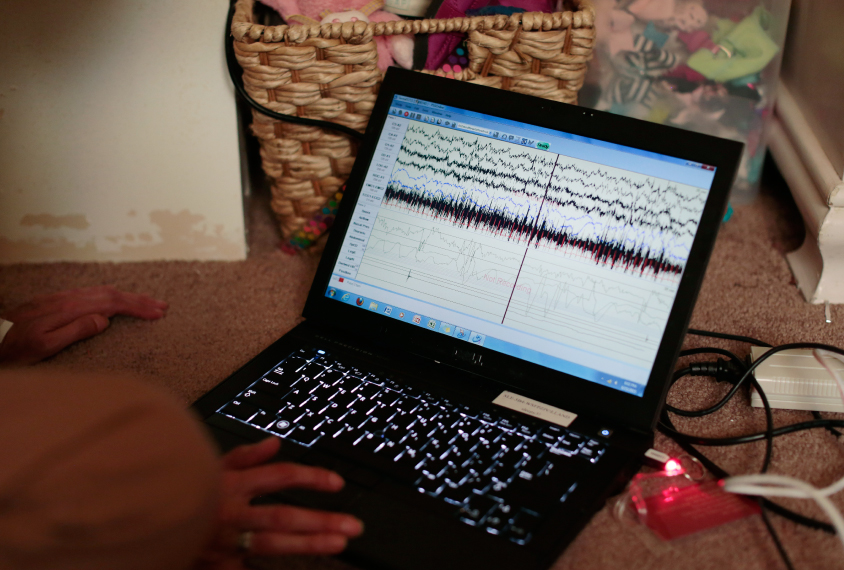

7:56 p.m. The sensors detect activity in the brain, heart, lungs and legs and send the data to a portable device, which records the information and can transmit it to a laptop computer. The researchers checked that the system was working properly, and then left for the night.

8:07 p.m. Initially agitated by the procedure, Bramli eventually quieted down. To keep her from ripping off the sensors, her mother got into bed beside her, took away all the toys, and tickled her arm to help relax her. Bramli finally fell sound asleep around 10:45 p.m. The mother then placed the final two sensors — a nose tube and an oxygen-measuring finger-clip device — on the child.

Home truth:

T

he Stanford researchers used an ambulatory version of the gold-standard objective technique for sleep studies, polysomnography. This is a laboratory procedure that records the brain’s electrical signals as a person cycles through different phases of slumber, such as REM sleep, and it reveals any abnormalities in this pattern, or ‘architecture,’ of sleep.Usually, polysomnography requires the participant to spend the night sleeping in the lab, wired with 21 electrodes stuck onto the scalp, legs and chest. For many children with autism who may be sensitive to unfamiliar people, environments and tactile sensations, that has been a nonstarter.

So O’Hara, working with sleep medicine specialist Michelle Primeau and other colleagues, improvised. The researchers used standard ambulatory equipment to bring the polysomnography method into a child’s bedroom, and devised a ‘systematic desensitization’ protocol to help get youngsters on the spectrum comfortable with the testing process.

They begin with preliminary home visits, bringing used or broken versions of the black spandex cap (with its embedded scalp electrodes), leg electrodes and other sensors so that the child can become familiar with wearing them. “Sometimes the children try the equipment on their dolls,” O’Hara says. Getting used to the gadgetry might take a child multiple visits over a week to two months, but surprisingly, most children are eventually able to tolerate it. Some older participants even enjoy seeing the real-time data recordings on the researchers’ laptop computer.

So far, 80 participants with autism ranging in age from 3 to 25 years have completed the overnight evaluation, which includes collecting breathing data — something rarely done with children who have autism, who may not readily put up with nose tubes or other airflow-monitoring devices. The team also collected home sleep data on 20 children with developmental delay and 44 typically developing children.

Thanks to the study’s creative approach, another important part of the sleep puzzle may be falling into place. The results are not yet published, but O’Hara says the most striking finding is that, like Bramli, 32 of the children with autism, or 40 percent, have apnea, compared with 11 children, or 25 percent, in the typically developing group. The implication is that at certain points during sleep, these children’s vulnerable brains don’t get enough oxygen. “That’s just not ideal for a growing and a developing child,” says O’Hara.

The Stanford investigation is “very well done” and valuable in highlighting the need to look for conditions such as sleep apnea in people with autism, says Beth Malow, a neurologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. But she notes that other studies have found sleep apnea in only about 1 to 6 percent of the general pediatric population — far lower than the 25 percent O’Hara’s group found.

O’Hara says that’s because earlier reports may have massively underestimated the problem. Those were based on surveys rather than on objective polysomnography — her study appears to be among the few to systematically assess breathing problems in autism using this gold-standard sleep-monitoring method — and do not reflect a newer diagnostic definition for pediatric sleep apnea. In any case, Malow agrees that apnea in any child is worrisome. The condition is associated with hyperactivity, she notes: It’s almost as though sleep-deprived youngsters try to fight their fatigue by being overly active.

Sleep patterns:

T

he Stanford home sleep data also revealed abnormalities in sleep architecture. The group with autism took a long time — about 160 minutes — to enter REM sleep and spent only 15.5 percent of the time in that sleep stage, which experts believe is crucial for normal brain development as well as processing of fear and emotions. By contrast, the control group took 100 minutes to reach REM and spent 25 percent of their sleep in that phase. (Bramli’s REM sleep looked relatively normal.)The REM findings echo those from another small polysomnography study, which found that 60 children with severe autism were in the REM sleep stage only 14.5 percent of the time, compared with 22.6 percent of the time among their typical peers. In that study, those with autism also got more slow-wave sleep, which is important for memory retention too.

O’Hara is analyzing whether the REM abnormalities she observed correlate with cognitive function or social responsiveness in the participants. She and her colleagues are also conducting another round of home polysomnography exams. To explore the origins of the REM differences, they are testing the children’s melatonin levels to examine whether a delayed circadian clock prevents them from getting sleepy during typical bedtime hours — keeping them from entering the first cycle of REM sleep and thereby reducing total REM time.

The research is still at an early stage, and in general, some of the most promising explanations for why sleep is elusive in autism have not yet provided any clear answers. About a decade ago, there were high hopes that differences in melatonin would explain the conundrum. Some groups had found that people with autism have low levels of the hormone, and other reports suggested that melatonin supplements can be helpful for many insomniacs on the spectrum.

But studies seeking to pin sleep disturbances on genetic mutations that cause shortages in melatonin have generated mixed and seemingly contradictory results, says Malow. These studies did not account for other factors that may interfere with sleep. “You have to look at the total picture,” Malow says. Some people with autism might have terrible ‘sleep hygiene’ — bad bedtime habits — or apnea. Others might have gene variations that disrupt other regulators of the circadian rhythm or that change how the body metabolizes melatonin.

Malow and her colleagues have been trying to clarify the picture by screening their study participants for sleep-disrupting medications and medical conditions, taking a comprehensive sleep history and educating parents on good sleep habits. Her group recently confirmed that some children with autism and delayed sleep onset do have mutations that lower their production of melatonin. But these children can also carry mutations that slow down the hormone’s breakdown in the liver, so that their overall melatonin levels are close to normal, Malow says.

Nailing down the relationship between sleep disturbances and melatonin is going to require large, well-controlled studies that carefully sort participants into subsets based on their sleep issues, melatonin levels and genes influencing melatonin production and metabolism. For now, she says, “we’re kind of in that middle zone where we haven’t come up with the solid answers yet.”

Combination therapy:

A

lthough the various reasons for sleep problems in autism are still being explored, there is good news for exhausted families: Sleep disorders are often treatable. “You can actually do something about it in a lot of cases,” O’Hara says.The first step is for a doctor to suss out what’s contributing to a child’s sleeplessness, whether that is apnea, epilepsy, low melatonin levels or something as simple as a bedroom that’s too warm. O’Hara says a full polysomnography assessment should be part of that evaluation, and because conditions such as apnea or periodic leg cramps may not be obvious, she advocates including the overnight sleep-monitoring procedure in the standard clinical workup for all children with autism. Doing this testing at home rather than in a lab is potentially cheaper and easier, and O’Hara notes that home polysomnography results generally correlate well with data recorded in the clinic.

With a comprehensive sleep evaluation in hand, a clinician can tailor the best combination of behavioral therapies, medications or other treatments to each individual with autism. For instance, in cases in which bad sleep habits are involved, children can benefit when parents establish better routines — from minimizing caffeine intake to restricting video games before bed.

When sleep apnea is part of the problem, addressing the condition can sometimes lead to dramatic improvements, as Malow and her colleagues saw in the case of a 5-year-old Tennessee girl on the spectrum. After the child had surgery to remove her tonsils and adenoids, she became more alert, affectionate and interactive, and her habit of spinning in circles resolved. Although it didn’t fully alleviate her autism symptoms, sleeping better probably eased the girl’s hyperactivity and generally “set the tone” for her to become more sociable, Malow says.

Finding the right combination of solutions can be a journey, as Haley Bennett and her husband have learned. The family always had well-structured bedtime routines, and melatonin therapy didn’t make much difference for Bramli. Although the girl definitely turned a corner after the tonsil surgery, Bennett suspects both Bramli and her brother Ryker have out-of-whack circadian clocks. Although the kids tend not to be very social during the day, once it’s time to go to bed, Bennett says, “all of a sudden, they’re more social; they’re happier; they want to play with a toy that they never want to play with.”

The family moved to North Dakota in August, but Bramli’s parents hope to bring her back for further research at Stanford. Bennett says their participation has taught her a lot about sleep already, and she plans to give melatonin or other recommended sleep strategies another try, in the hopes that they will help at some point when the children are older.

Meanwhile, she says, the family members cope as best they can in the nightly struggle to get enough shut-eye. “I try to have a sense of humor about it and keep perspective that there are worse problems to have.”

Recommended reading

Building an autism research registry: Q&A with Tony Charman

CNTNAP2 variants; trait trajectories; sensory reactivity

Brain organoid size matches intensity of social problems in autistic people

Explore more from The Transmitter

Cerebellar circuit may convert expected pain relief into real thing