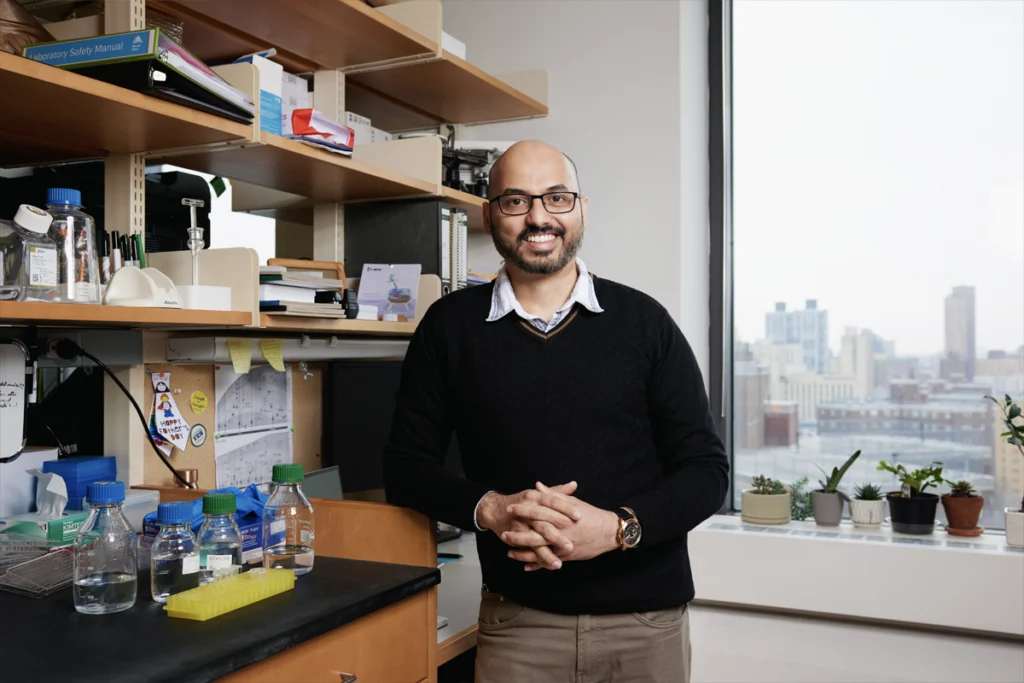

Susan Masino loves forests — so much so that she has said she would love a second career as a naturalist. For now, though, she juggles her increasing environmental public policy efforts and advocacy for green spaces with her decades-long scientific career at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. There, as Vernon D. Roosa Professor of Applied Science, she teaches neuroscience and psychology to undergraduate students and researches links between metabolism, brain activity and behavior, as well as the mechanisms that underlie the ketogenic diet’s anti-seizure effects.

In recent years, Masino has found ways to blend her work in the woods, lab and classroom; last May, she helped to get Trinity’s 100-acre campus designated as an arboretum. She also regularly lectures on the potential benefits to brain health from spending time in nature.

The Transmitter caught up with Masino in November at the 2023 annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in Washington, D.C., where she received the Louise Hanson Marshall Special Recognition Award, which “honors individuals who have significantly promoted the professional development of women in neuroscience through teaching, organizational leadership, public advocacy, or other efforts.” She talked about learning to be a scientist, balancing her multidisciplinary interests, and the smell of dirt in the woods.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: Did you always know you wanted to be a scientist?

Susan Masino: I’m actually a first-generation college student. I did want to be a scientist, but I had no idea how to do it. I had to kind of figure that out as I went along. And I didn’t realize that you could get paid to go to graduate school in science.

TT: Was there anyone who was a particularly important mentor?

SM: One of my professors said, “At this stage of your career, the most important thing is the mentorship you receive and not necessarily the topic you’ll be working on.” So I spent a few years after my undergraduate degree working in a cell biology lab. And that lab gave me the freedom to design my own experiments and really be a full-fledged member.

TT: How do you balance your interests in both neuroscience and nature?

SM: I have to shift my focus to one versus the other when needed, and put one on the backburner. I’m fortunate to be able to have some of my teaching related to my nature and brain health interests. We just designated the campus as an arboretum, and integrating that into my classes and into my student research will be an ongoing opportunity to talk about ecology and health.