Some autism risk may arise from sex-specific traits

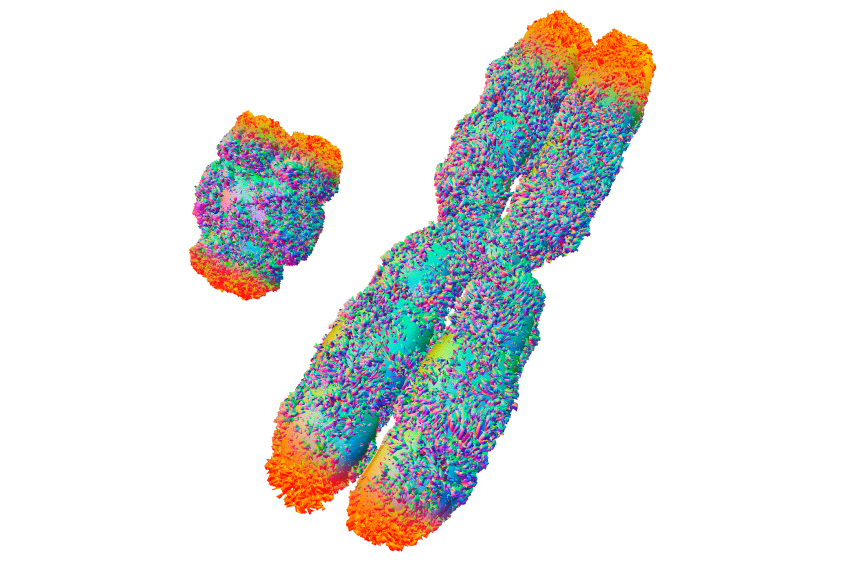

Genetic variants that shape physical features that vary with sex, such as waist-to-hip ratio, may alter autism risk.

Editor’s Note

After this story ran, we discovered that the writer, Ann Griswold, has a personal conflict of interest with the STAR Center at the University of California, San Francisco. Lauren Weiss, who is quoted in the story, is affiliated with the center. We do not believe this alters the content or tone of the story. Nevertheless, we apologize for this oversight.

Genetic variants that shape physical features that vary with sex, such as waist-to-hip ratio, may also affect autism risk, according to a new study.

Many of the genes involved in these features are not linked to autism or even the brain. Instead, they help establish basic physical differences between the sexes, says lead investigator Lauren Weiss, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

“Whatever general biological sex differences cause a [variant] to have a different effect on things like height in males and females, those same mechanisms seem to be contributing to autism risk,” she says. The work appeared in November in PLOS Genetics.

The results bolster the notion that mutations in some genes contribute to autism’s skewed sex ratio: The condition is diagnosed in about five boys for every girl. That may be because girls require a bigger genetic hit to show features of the condition, because sex hormones in the womb boost the risk in boys or because autism is easier to detect in boys than in girls.

The new study is the first to look at sex differences in common genetic variants called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). It shows that the sexes differ in which autism-linked SNPs they have, but not in the overall number of such SNPs.

Separate sets:

Weiss and her team analyzed published genetic data from four databases and unpublished data from five others. Altogether, they reviewed information from 8,646 individuals with autism, including 1,468 girls and women. They also analyzed data from 15,028 controls, some of whom are related to people in the autism group.

The researchers first identified SNPs that differ between males with autism and their unaffected family members and unrelated controls. They then repeated the procedure for girls and women with autism.

These two analyses revealed distinct sets of SNPs associated with autism: a set of five SNPs in boys and men and a separate set of three SNPs in girls and women. None of the variants have previously been associated with autism.

The researchers then compared males who have autism with females who have the condition. They found similar levels of genetic variation in the two groups, with equal numbers of autism risk genes affected. This result suggests that common variants do not contribute to a stronger genetic hit in girls with autism.

Body of data:

When the researchers compared people who have autism with controls, they did not find any differences in SNPs in genes that respond to sex hormones.

The team then looked at 11 SNPs known to influence height, weight, body mass index, hip and waist measurements in women, and 15 variants that influence these physical traits in men. They found more of these sex-specific SNPs in people with autism than in controls. None of these SNPs have previously been associated with autism.

The findings suggest that different SNPs contribute to autism risk in boys and girls.

The fact that some of these SNPs also shape physical traits in a sex-specific way is particularly interesting, says Meng-Chuan Lai, assistant professor in psychiatry at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the study. Scientists should examine whether sex differences in brain structure in people with autism track with the sex-specific SNPs, he says.

Weiss says she hopes the findings will spur researchers to pay more attention to the influences of sex when sifting through genomic data. Outfitting genetic repositories with the option to sort data by sex would be the next step for that approach.

References:

- Mitra I. et al. PLOS Genet. 12, e1006425 (2016) PubMed

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature