Clinical research: Mainstreaming helps children with autism

Early interventions for preschoolers who have autism are effective when included alongside standard curricula in mainstream settings, according to two studies published in April.

Early interventions for preschool-aged children who have autism are effective when included alongside standard curricula in mainstream settings, according to two studies published in April.

Studies in the past few years have shown that early behavioral intervention is a promising treatment for children with autism, but can be expensive and difficult to implement on a large scale. Parents also don’t always enroll their children in these programs, even when the interventions are freely available.

The new studies describe preschool programs that teach children with autism alongside their typically developing peers. Both programs include children as young as 2 years, the age at which doctors can first reliably diagnose the disorder.

In the first study, published 7 April in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, researchers looked at 31 children with autism, aged 2 to 6 years, enrolled in a new preschool inclusion program in Oslo, Norway1.

There are other intervention programs in Oslo at mainstream schools, but those require additional staff and cost for each child with the disorder. The new program instead trained and supervised existing faculty to implement the program.

After two years, six of the children improved by more than 27 points on a measure of their intelligence quotient (IQ). Another two improved significantly — by more than 21 points — in social behavior, as measured by a composite score on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales.

None of the 12 controls, who were enrolled in the other mainstream programs, improved significantly on either of the measures.

In the second study, published 12 April in Autism, researchers followed 102 children enrolled in a community toddler program starting at age 2 for up to a year2. Classes included eight typically developing toddlers, joined by four toddlers with autism in the mornings and another four in the afternoons.

The program entailed three hours each day of intensive training, including structured teaching and pivotal response training, which incorporates applied behavioral analysis, the standard treatment for autism, into a natural setting. Teachers are also trained to encourage typically developing toddlers and those with autism to play together by interacting with them at the same time. Parents also agreed to give the toddlers with autism ten hours each week of additional interventions at home.

At the end of the program, the developmental level of the children with autism changed significantly, as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development and the Mullen Scales of Early Learning. These measures test motor, visual and language skills.

Based on these measures, the number of children with autism who were in the typical range of development rose from 6 to 31 percent by the end of the program. More than half of the children who were in the severely impaired range of functioning moved into the mildly delayed or the typical range.

This study did not include a control group. However, the researchers had predicted the expected level of development based on the children’s developmental trajectory when they entered the program. The children were, on average, at a 16 percent higher developmental level than expected.

References:

-

Eldevik S. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

-

Stahmer A.C. et al. Autism Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

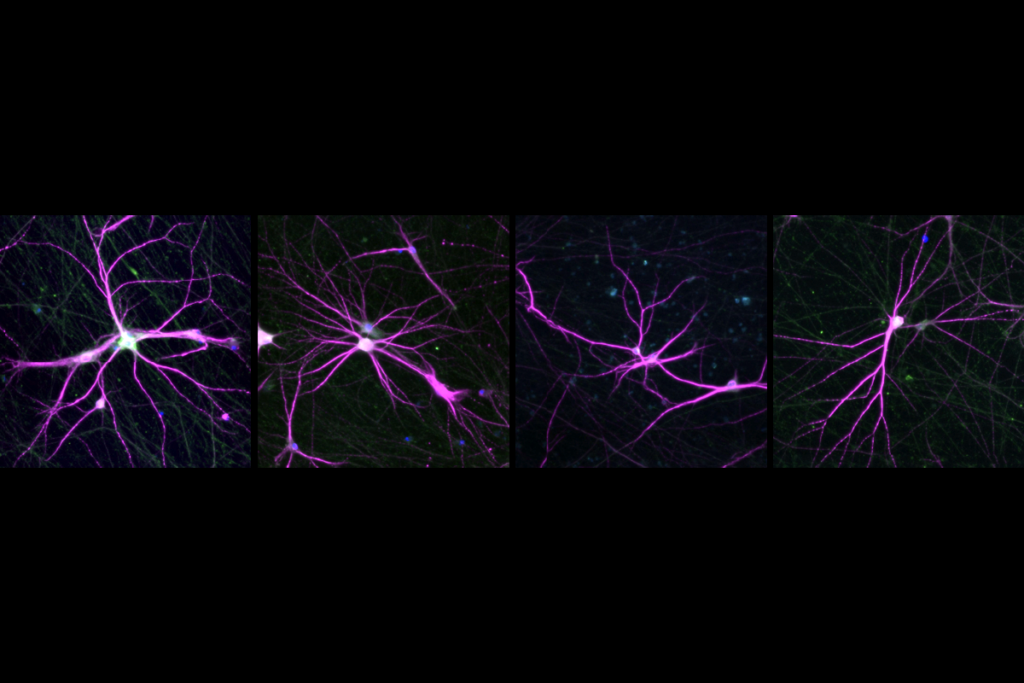

Cortical structures in infants linked to future language skills; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter