Welcome back to Spectrum’s Community Newsletter, our first in 2023. Researchers kept the conversation on Twitter motoring along over the holidays and this week we’re highlighting three threads tied to movement.

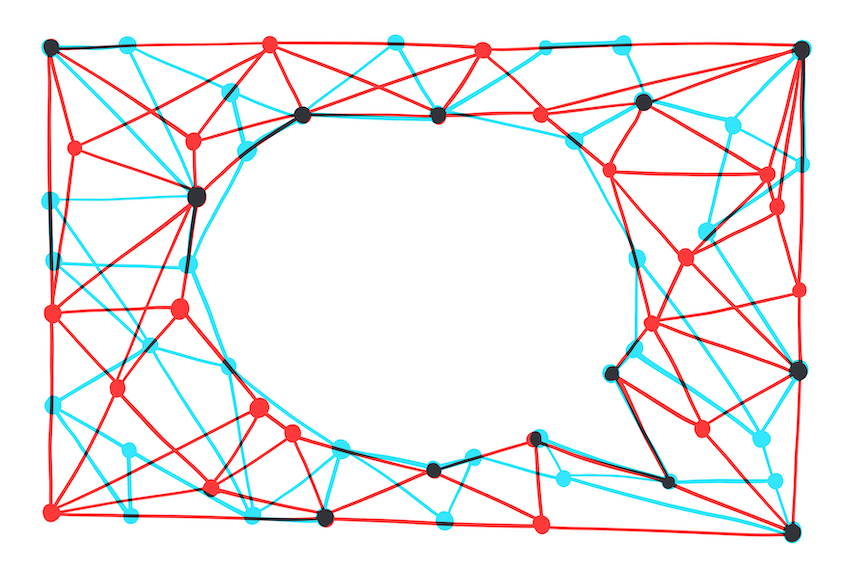

A new method dubbed SHAMAN — for Split Half Analysis of Motion Associated Networks —can help researchers who have conducted certain brain-imaging experiments determine if their observed “brain-behavior correlation was affected by head motion,” tweeted study investigator Benjamin Kay, assistant professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Ever wondered if your interesting brain-behavior correlation was affected by head motion, but were afraid to ask? We’ve created a motion impact score for detecting spurious brain-behavior associations. Excited to share my 1st preprint on Science Twitter! https://t.co/3gDH7zSb8K pic.twitter.com/lkcpiSvKbr

— Benjamin Kay (@ScienceBenKay) December 22, 2022

The approach, described in a bioRxiv preprint in December, reveals whether “trait-functional connectivity (FC) correlations are biased by residual motion artifact in order to avoid reporting false positive results,” Kay and his colleagues wrote.

In a reply, Vince Calhoun, founding director of Translational Research in Neuroimaging and Data Science in Atlanta, Georgia, wondered if the method might incorrectly flag certain effects because it assumes “that the repertoire of behaviorally relevant (and irrelevant) FC is unchanged (& evenly sampled) in different subsets of data.”

You’ve articulated a key assumption underpinning motion impact score, and a potential obstacle to using this for fMRI involving a motor task. However, for resting-state, we think it’s safe to assume second-to-second variation in FD is unrelated to a behavioral trait’s FC.

— Benjamin Kay (@ScienceBenKay) December 26, 2022

“You’ve articulated a key assumption underpinning motion impact score,” replied Kay, who agreed that it represents a potential obstacle to using SHAMAN for functional MRI studies involving a motor task, but not for resting-state scans.

Matthew Heindel, a graduate student at University of Southern California in Los Angeles, tweeted that the tasks he often uses in his research “are particularly prone to motion artifact that’s correlated with the task, and extensively evaluating this relationship is essential.”

In the neuroimaging literature of msk pathologies, our task-based paradigms often include muscular activation tasks. These are particularly prone to motion artifact that’s correlated with the task, and extensively evaluating this relationship is essential. Thanks, Benjamin! https://t.co/xLTjRWu2kZ

— Matt Heindel, PT, DPT, OCS (@heindelm) December 23, 2022

Switching gears to another movement-related study, researchers also recently investigated “the effects of spontaneous movements on cognitive processing in the macaque cortex,” tweeted Camille Testard, a graduate student in Michael Platt’s lab at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

**STOKED** to see our work with @seb_trem & co out in @NatureNeuro today!

We investigate the effects of spontaneous movements on cognitive processing in the macaque cortex.https://t.co/6cbJyOpeEn

Detailed tweeprint below ???? https://t.co/AcwjcogpBW

— Camille Testard (@CamilleTestard) December 19, 2022

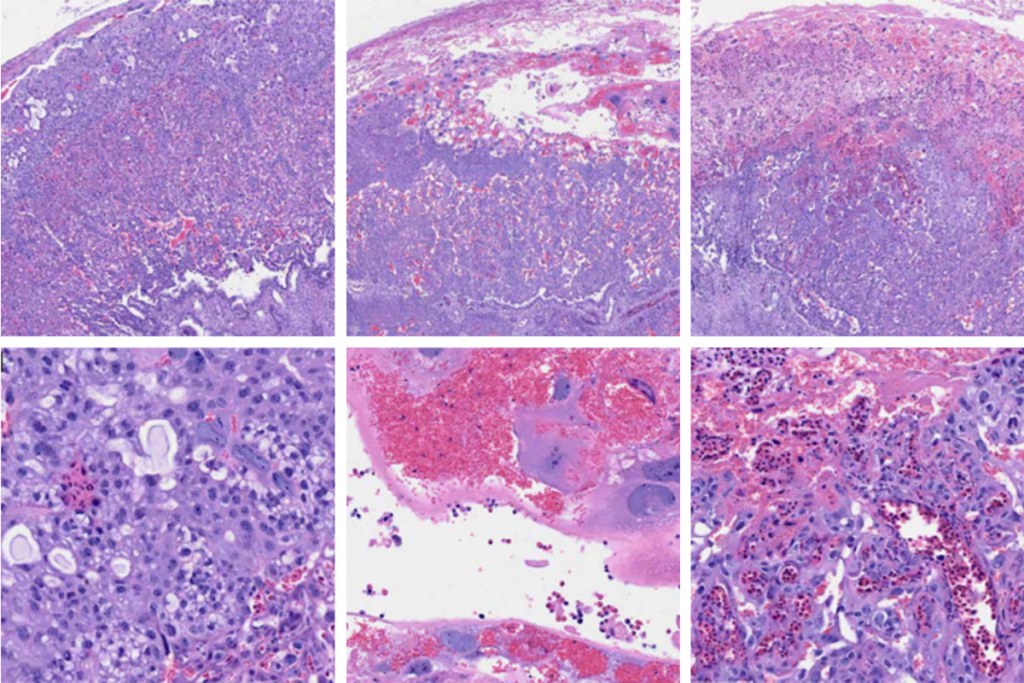

Testard and her colleagues recorded brain activity and body movements in unrestrained monkeys performing cognitive tasks and found that the two measures were closely tied: “neural variance is in large part explained by movement, and movements largely align with task variables,” Testard wrote. This correlation suggests that movement, as well as restricting it, can potentially confound neurophysiological studies of cognition, she concluded. Instead of restraining animals during brain imaging, their movements “should be monitored to disentangle cognitive signals from movement signals in monkeys!”

To conclude: decision signals in the PFC are robust to movement, opening the door to studying cognition under naturalistic conditions. BUT movements, including uninstructed ones, should be monitored to disentangle cognitive signals from movement signals in monkeys! 9/11 pic.twitter.com/RCcCm578zV

— Camille Testard (@CamilleTestard) September 7, 2022

This result “adds to the debate launched by @anne_churchland et al in mice,” wrote Platt in response to a tweet from Testard that shared a link to the preprint in September 2022.

Important new work from current PlattLabbers @seb_trem and @CamilleTestard showing that spontaneous movements account for a lot of “cognitive” signals in primate PFC but task info can still be decoded. Adds to the debate launched by @anne_churchland et al in mice https://t.co/wfShfQ87t3

— Michael Platt (@MichaelLouisPl1) September 7, 2022

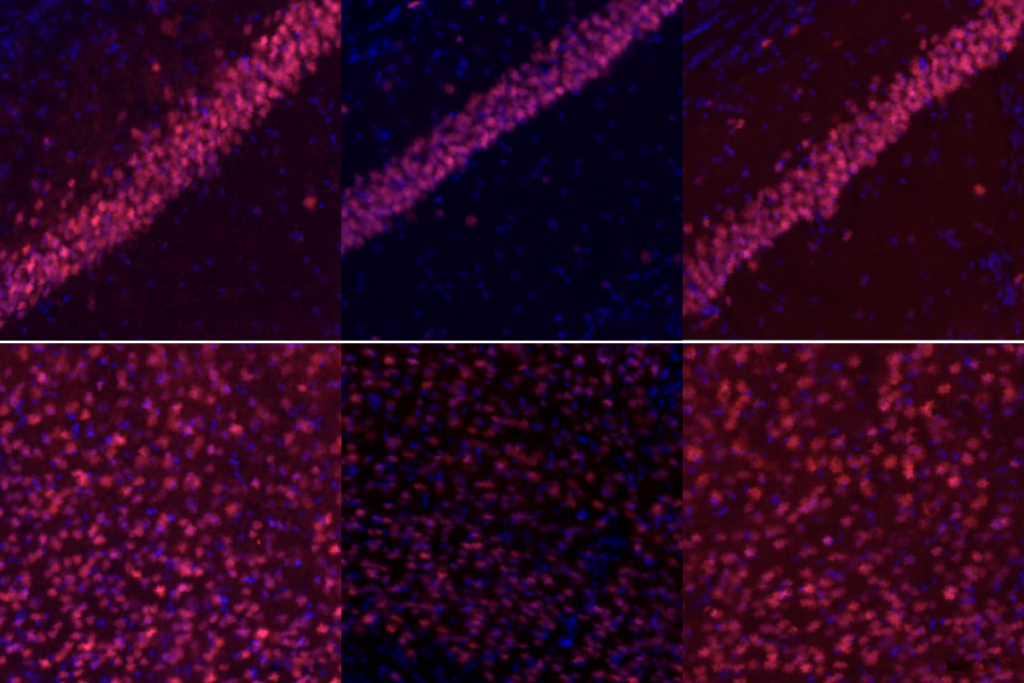

Yet another study highlighted on Twitter over the holidays implicated motor areas in the brain in autistic children’s “reduced phonological working memory as measured by nonword repetition,” tweeted Zhenghan Qi, assistant professor of communication sciences and disorders and psychology at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts.

Autistic children often show reduced phonological working memory as measured by nonword repetition. Our work, led by @Amanda_M_OBrien, investigates which brain networks (speech perception, working memory, or speech production) underlie such difficulties. https://t.co/GGXL96yvOk

— Zhenghan Qi (@qzhever) December 28, 2022

“We found reduced & atypical speech-motor system activation related to phonological working memory difficulties for autistic children,” tweeted study investigator Amanda O’Brien, a graduate student at Harvard University.

I had the pleasure of learning from @qzhever, @NeuroTyler, @gabrieli_john, & @HelenTager while working on this project. We found reduced & atypical speech-motor system activation related to phonological working memory difficulties for autistic children. See @zqhever’s thread! https://t.co/yTRsSY7ZaF

— Amanda Marie O’Brien (@Amanda_M_OBrien) December 28, 2022

“Fascinating study highlighting why we need more research focused on motor speech in autism!” tweeted Camille Wynn, assistant professor of communication sciences and disorders at the University of Houston in Texas.

Fascinating study highlighting why we need more research focused on motor speech in autism! https://t.co/hTcO1XNl6N

— Camille Wynn (@CamilleJWynn) January 2, 2023

That’s it for this week’s Community Newsletter! If you have any suggestions for interesting social posts you saw in the autism research sphere, feel free to send an email to [email protected].

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter (@Spectrum), Instagram and LinkedIn.

Subscribe to get the best of Spectrum straight to your inbox.