Postmortem brain study hints at cell types involved in autism

An unprecedented look at gene expression in tens of thousands of brain cells from autistic people suggests important roles in the condition for a neuronal subtype and for microglia.

An unprecedented look at gene expression in tens of thousands of brain cells from autistic people suggests important roles in the condition for a subtype of neuron and for microglia.

Researchers presented the findings yesterday at the 2018 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, California.

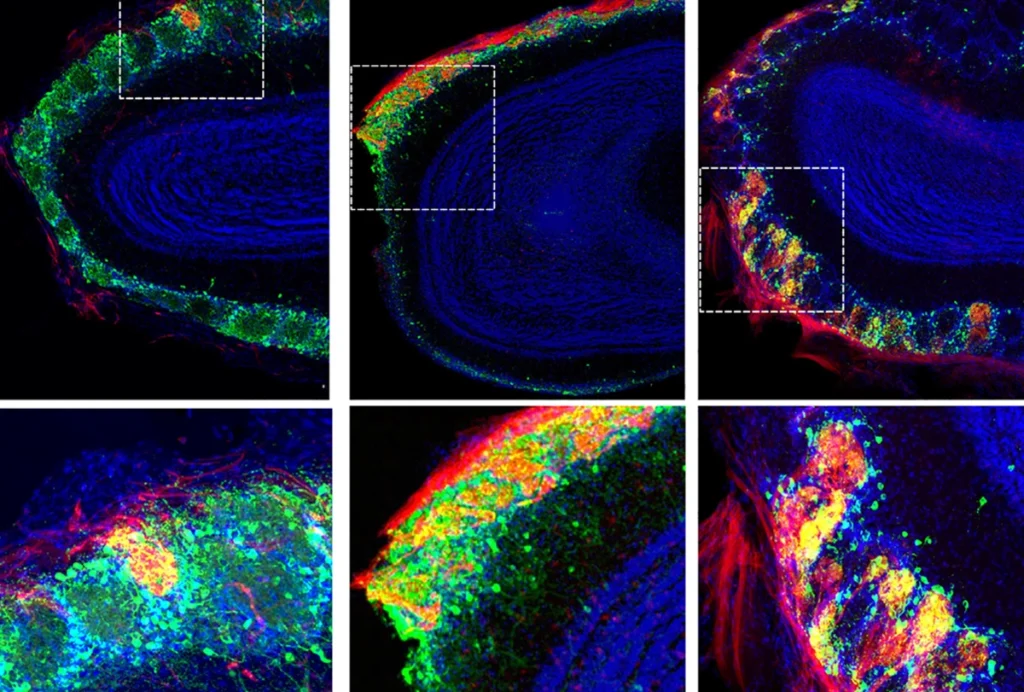

The researchers mapped the gene expression patterns of more than 100,000 individual cells from the brains of 15 people who had autism and 16 controls. They looked specifically at two brain regions, the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, both of which have been implicated in autism.

In postmortem brain studies of gene expression, researchers typically grind chunks of brain tissue, lumping together different types of cells. The new study uses advanced technology that enables researchers to isolate the nuclei of individual cells. The researchers then sequence the RNA, the genetic message that codes for protein, from each nucleus.

This approach makes it possible to tease apart the multitude of cell types in the brain and assess which are most important in autism, says Dmitry Velmeshev, a postdoctoral associate in Arnold Kriegstein’s lab at the University of California, San Francisco, who presented the findings yesterday.

“The idea was to look at the cell-type-specific gene expression changes in autism,” Velmeshev says. “This is something we couldn’t do before single-cell sequencing became available.”

Brain effects:

Overall, the researchers found 458 genes expressed differently in neurons from the autism brains, and 234 expressed differently in other brain cells, compared with controls. This list includes several top autism genes, including ARID1B, NRXN1 and PTEN.

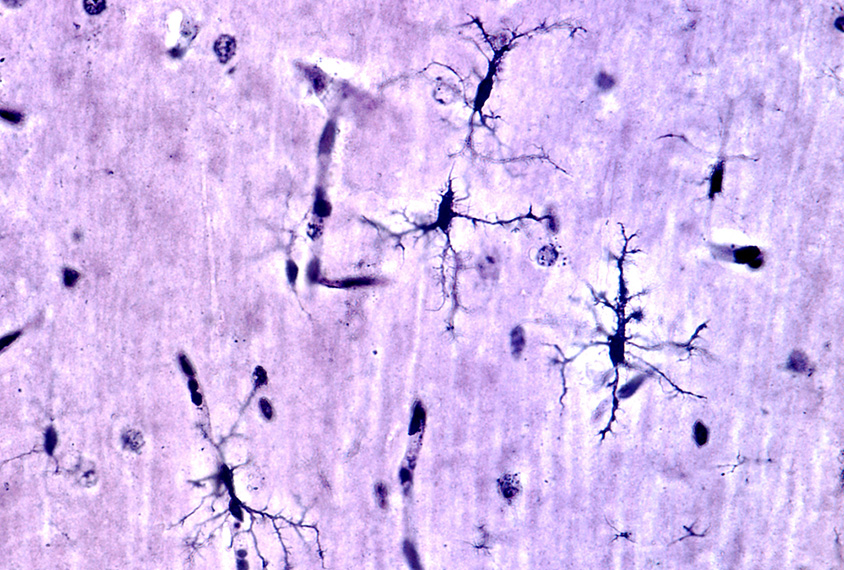

Genes in a subset of neurons in layer 2/3 that excite brain activity and project to other neurons in the cortex tend to show diminished gene expression; genes in microglia show enhanced expression. These two cell types, as well as layer 4 excitatory neurons, show the strongest changes in gene expression.

The researchers then looked at an autism severity score for each of the autistic individuals who had donated their brains; this score is based on the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, a diagnostic test for the condition.

The individuals with higher severity scores also show the most changes in gene expression in layer 2/3 neurons, microglia and somatostatin interneurons, which regulate brain activity.

The researchers repeated their analysis in an additional eight brains from people who had epilepsy but no autism traits, and seven controls. Only roughly 10 percent of the genes altered in this analysis show an overlap with the autism results. This hints at a gene expression signature that is distinct from that of epilepsy, Velmeshev says.

For more reports from the 2018 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’