Takeaways from SfN 2014

Scientists reflect on the current state of autism research as the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C. comes to a close.

Going into the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, I’ll admit, I felt unprepared. It just seemed too soon. Really, it’s been one year already?

Yet 2014 is truly rounding the final bend, as corroborated by the 20-degree Fahrenheit wind that greeted attendees here in Washington, D.C. on the meeting’s final morning. And neuroscientists made notable progress this year, as evidenced by the number of newsworthy results presented here.

First, let’s make one thing clear: SfN is a beast. This year, 31,000-plus attendees packed more than 15,000 presentations into five hectic days. With fields ranging from autism to Alzheimer’s, and techniques from optogenetics to imaging, trying to find common threads felt a little bit like pulling at a Coogi sweater.

Still, a handful of overarching takeaways emerged, especially in terms of implications for autism and related disorders. Nothing can get you more up to speed on these findings than the 50 breaking news items the SFARI.org news team rapidly produced throughout the conference. Find those articles here.

I’ll focus my wrap-up on the various takeaways I gleaned running around the giant three-chamber maze that is the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, talking to attendees and organizing online interactions among researchers.

A second life:

Many provocative discussions at the annual conference happen in between sessions, over lunch or, increasingly, online on Twitter or Facebook.

While roaming this year’s poster halls, Dwayne Godwin, professor of neurobiology and anatomy at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, asked what others thought about a study hinting at fundamental problems with diffusion tensor imaging, a popular brain imaging technique. This led to an extended discussion on Twitter among scientists at the meeting and elsewhere about the study’s implications for research.

On the penultimate day of the conference, scientists and journalists huddled over mobile devices and cold flatbread to ponder key questions in autism research via our live Twitter conversation.

(You can find an edited Storify version of the conversation here. A full transcript of the chat is here.)

Singular focus:

At a pre-conference satellite symposium, researchers presented a trove of new work on SHANK3, a leading autism candidate gene. One team of researchers showed how different variants of the gene have diverse effects in mice. Another group presented results of a preliminary clinical trial of a drug that improves symptoms in people who have a SHANK3 mutation.

“A considerable amount of heavy lifting has been done in mouse studies of SHANK3,” Matt Mosconi told me. “But translating findings on possible targets for therapeutics in the clinic will take significant resources and a greater emphasis on identifying appropriate biomarkers and quantitative endpoints.”

Some researchers believe that mutations in single, rare genes provide the least complicated targets for potential therapies — and that, in the long term, they may also provide mechanistic insight into more complex forms of autism with similar symptoms. As Partha Mitra said during our Twitter chat, “We still need to understand ‘final common pathways’ causing the common phenotype.”

In one standing-room-only symposium, researchers revealed a number of unpublished mouse studies suggesting ways in which the immune system contributes to neuropsychiatric disorders.

“The interest in neuroimmunology was remarkable,” Melissa Bauman told me. “It’s becoming clear that interactions between the immune and nervous systems influence behaviors that are altered in neurodevelopmental disorders.”

Jonathan Kipnis, who led some of this work, is an unabashed cheerleader for this field. “Microglia is the next (or the current) big thing in neuroscience,” he tweeted.

Another advantage of the diversity of topics at the conference is that it gives attendees a good opportunity to copy pages out of one another’s lab books. For instance, autism researchers can see what’s working for scientists studying schizophrenia, brain tumors or Parkinson’s disease.

Valerie Hu, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., says she hopes such commingling will lead to more creative approaches in autism.

“I was pleased to see that autism researchers are increasingly embracing a systems approach, both at the level of integrative systems biology as well as at the level of systemic physiology,” she told me. “This integrates the interactions of brain-gut-immune systems as contributors to autism.”

Like us on Facebook » | Follow us on Twitter @SFARIorg » | Join our newsletter »

For more reports from the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Explore more from The Transmitter

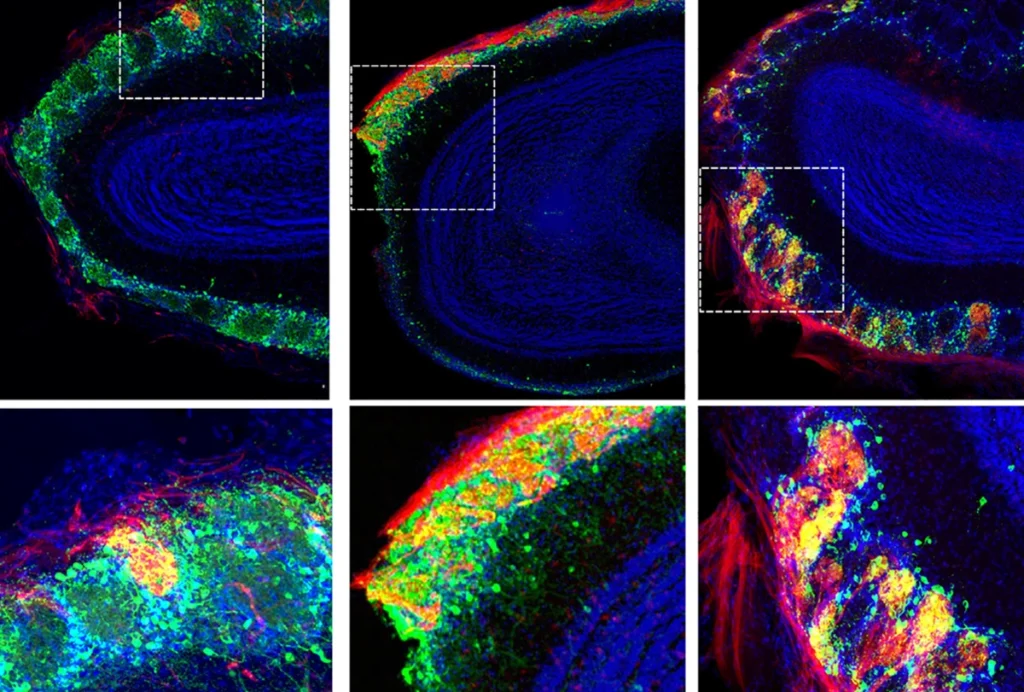

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’