Behavioral treatment for autism may normalize brain activity

Early intensive therapy may normalize the brain’s response to faces in young children with autism, according to a study published in the November issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The results are part of a randomized, controlled trial of a treatment called the Early Start Denver Model.

Early intensive therapy may normalize the brain’s response to faces in young children with autism, according to a study published in the November issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry1.

After two years of behavioral therapy for about 20 hours each week, the brains of young children with autism respond to faces like those of typically developing controls do, the study found.

The results are part of a randomized, controlled trial of the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM), in which clinicians spend many hours each week working one-on-one with children in play-based therapy.

“Many people think about behavioral interventions as kind of a simple Band-Aid operation,” says Sally Rogers, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Davis, who helped develop ESDM and was involved in the new study. “Early intervention can make a difference at levels of learning much deeper than the surface level of behavior change.”

Rogers and her colleagues do not have enough data to compare brain activity before and after treatment, but children with autism are known to have an abnormal response to faces.

The study is based on electroencephalography (EEG), an indirect measure of the brain’s electrical activity, and is among the first to look at how behavioral therapy influences brain activity.

“There are a fair number of behavioral studies showing the beneficial effects of an intervention, but until this study none really focused on what changes were also occurring in the brain,” says Charles Nelson, professor of pediatrics and neuroscience at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the work.

Rogers and her colleagues reported in 2010 that children who receive the therapy develop better language and daily living skills, and increase their intelligence quotients (IQs) more than do those who receive other autism treatments2.

The new study found that one measure of the brain’s response to faces looks normal in children who have received ESDM or otherbehavioral therapies for autism. But twoother measures are normal only in the ESDM group.

The study reflects a broader trend to seek objective measures, or biomarkers, to help evaluate the effects of autism treatment. “It really represents where our field is moving,” says Shafali Spurling Jeste, assistant professor of psychiatry and neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study.

Brain waves:

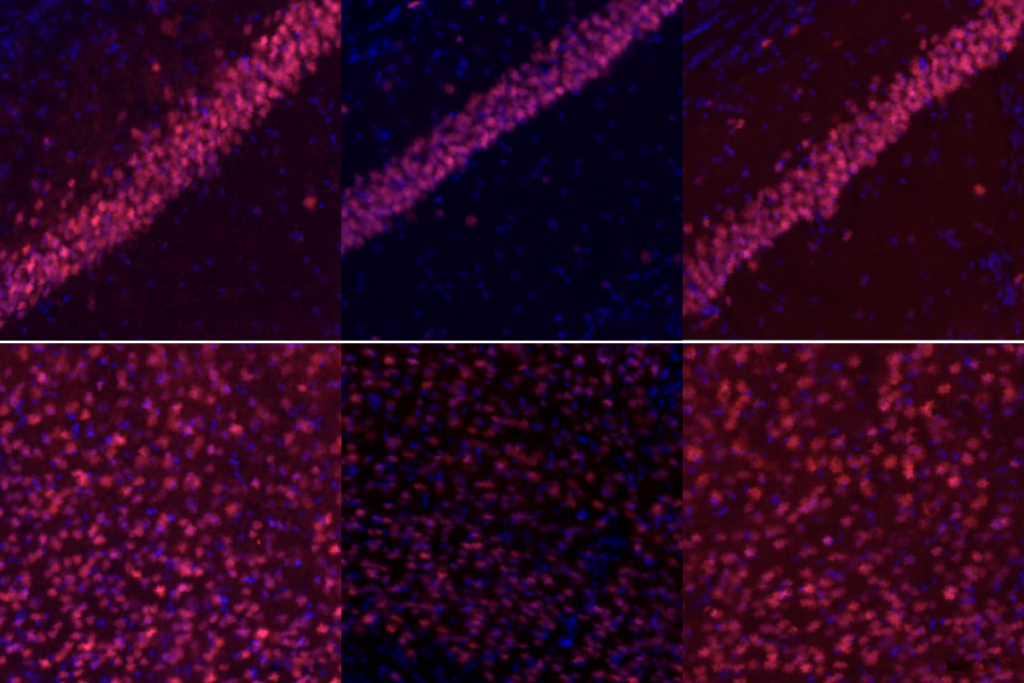

The researchers used EEG to measure the brain activity of children aged 4 to 6.5 years while they viewed images of unfamiliar faces and toys on a screen. They were able to do this with only a subset of the children from the 2010 study.

The EEG participants included 15 children with autism who had completed a two-year program of ESDM, 14 who had received other behavioral therapies available in the community and 17 typically developing controls.

Previous research has shown that children with autism have an atypical N170, an EEG measure that reflects the brain’s early response as it recognizes that a face is a face.

In the new study, the researchers found that children with autism who received ESDM and those who received community interventions all have N170 patterns similar to those of the controls.

“That would suggest to us that both groups had benefited,” says Sara Webb, research associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington, who directed the EEG part of the study.

Webb notes that the community intervention group also had access to at least 15 to 20 hours of therapy each week. “So I think one conclusion [we] can make is that getting early intervention is critically important.”

The ESDM may have additional benefits compared with the other interventions, however. The researchers also measured alpha and theta brain waves in the children, as well as an EEG feature called the negative component.

These analyses “reflect the degree to which your attention is captured by a stimulus, and also your active involvement in processing that stimulus,” says lead investigator Geraldine Dawson, chief science officer of the autism science and advocacy organization Autism Speaks and co-developer of the ESDM.

On average, children with autism who received ESDM and controls have more and faster neural activation in response to images of faces compared with images of toys. In contrast, children who received other therapies respond more to the toy images.

Taken together, the results suggest that although both types of therapy help children with autism process faces, ESDM makes them more attentive to faces.

“Really it makes sense in terms of the fact that the ESDM has a very strong focus on drawing the child’s attention to people, but also making those interactions with people very rewarding,” Dawson says.

The researchers also found that the children who received ESDM have fewer autism symptoms at the end of the study than those treated with other therapies.

Some researchers caution that because the analysis relies only on post-treatment EEG data, it provides a snapshot of brain activity. “The ideal way to look at change is to look at these kids over time,” says Jeste. “We don’t know what these kids looked like before.”

Webb acknowledges this limitation, but notes that the researchers have limited EEG data from before the study began and at the one-year time point showing that children with autism differed from controls3.

The children in the two treatment groups were so similar behaviorally at the beginning of the study, it’s unlikely that their brain function differed significantly, she adds.

Other researchers are also beginning to look at neural measures of treatment effects. For example, a magnetic resonance imaging study of two children with autism published in October found that pivotal response training, an intervention that, like ESDM, teaches skills through play, increases activation in social areas of the brain4.

As researchers develop EEG-based biomarkers that indicate treatment response, they will also need to find ways to reliably collect EEG and other imaging data from children.

“I think the beauty here is that this gets us beneath the skin, beyond the level of description,” Nelson says. “These brain changes may serve as an index as to what is driving the changes in behavior.”

References:

1: Dawson G. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 51, 1150-1159 (2012) PubMed

2: Dawson G. et al. Pediatrics 125, e17-e23 (2010) PubMed

3: Webb S.J. et al. Child Dev. 82, 1868-1886 (2011) PubMed

4: Voos A.C. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

Post-infection immune conflict alters fetal development in some male mice

In-vivo base editing in a mouse model of autism, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: Spying on the secret sensory world of ticks

Lack of reviewers threatens robustness of neuroscience literature