People with autism who are diagnosed earlier as opposed to later in life have distinct genetic profiles, according to a study published last month in Nature.

Many factors may influence when someone receives their diagnosis, and several theories explain how genetics contributes. By one line of thinking, people who have subtle autism-related traits during early childhood have fewer of the genetic variants linked to the condition. These people may only receive a diagnosis later in life, for example when social demands increase and their autism-related characteristics become easier to recognize.

But the new work pushes back against those assumptions. “What we’re showing is that that’s not entirely true,” says study investigator Varun Warrier, associate professor of neurodevelopmental research at the University of Cambridge.

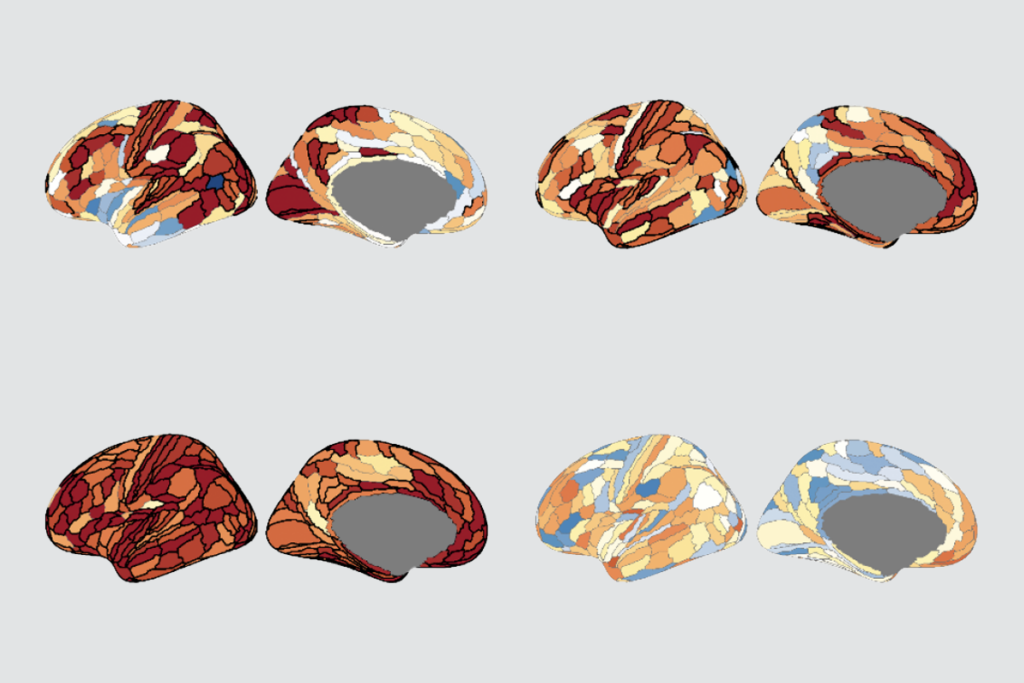

Instead, he and his colleagues found evidence that autism diagnosed early in life and autism diagnosed later have different genetic underpinnings. More specifically, they identified two distinct trajectories tied to behavior and age of diagnosis, and that, separately, age of diagnosis corresponds to distinct genetic profiles that only modestly overlap with one another.

People diagnosed later in life also tended to experience higher rates of mental health conditions, such as ADHD and anxiety, Warrier adds. Taken together, the findings suggest that autism diagnosed early and late in life might constitute two distinct autism subtypes, he says.

“I think there are lots of questions about whether they can replicate these findings” in other cohorts, says Catherine Lord, distinguished professor of psychiatry and education at University of California, Los Angeles. It’s difficult to fully tease apart potential environmental and developmental factors that might have contributed to the between-group differences in the study, Lord says. Still, “it’s a great start,” she adds.

I

n a multi-part investigation, Warrier and his colleagues first used longitudinal behavioral data from three birth cohorts, ranging in size from 89 to 188 people, that tracked socioemotional and behavioral development. Different behavioral trajectories were linked to age at autism diagnosis, this analysis confirmed. In the group more likely to receive an early diagnosis, social and communication challenges arose in early childhood, around age 6, and remained stable or declined slightly in adolescence. In the other group, more likely to receive a later diagnosis, children showed fewer early difficulties, but these increased with age.To assess how genetic variation differed with age at diagnosis, the investigators used genomic data from two large studies: the SPARK project and the iPYSCH cohort, which provided genetic data for 18,965 and 28,165 people with autism, respectively. (SPARK is funded by the Simons Foundation, The Transmitter’s parent organization.) The researchers pinpointed two distinct genetic signatures associated with an earlier autism diagnosis, meaning ages 3 to 6 on average, or later, after about age 10.

In total, differences in single-nucleotide polymorphisms accounted for 11 percent of the variance in age at which people were diagnosed. No link was found between rare de novo variants and age at diagnosis.

The specific variants associated with autism, and their effects on likelihood, differed with the age at diagnosis, the investigators found through genome-wide association studies. A correlation analysis revealed two broad, slightly overlapping genetic factors—or groups of common variants—associated with early and late autism diagnoses.

The groups of variants associated with an early versus late autism diagnosis were only moderately correlated with each other. This finding again points to two largely distinct sets of common variants linked with age at diagnosis, Warrier says.

Finally, the group of variants associated with a later diagnosis correlated more strongly with mental health conditions, such as ADHD, depression and anxiety, than did the group of variants tied to an earlier diagnosis, the study showed. But whether these comorbidities have genetic underpinnings or reflect environmental influences is unclear, Warrier says. “Some of the things we want to look at are: What are the environmental factors that mediate the link between a genetic predisposition to mental health outcomes?”

I

ndeed, clinical and socioeconomic factors, such as a family’s economic resources and access to care, can influence the timing of diagnosis and merit further investigation, he says. Still, less than 15 percent of the variance in age of diagnosis can be explained by such factors, Warrier and his colleagues calculated in a supplemental analysis, using data from past research. But other unmeasured socioeconomic and environmental factors may also contribute to age of diagnosis, Warrier says.“This is a really exciting paper,” says Natalie Sauerwald, associate research scientist at the Flatiron Institute, who was not involved in the work. (The Flatiron Institute is funded by the Simons Foundation, The Transmitter’s parent organization.) “Being able to pull apart these different presentations of autism is going to allow us to better understand the genetic heterogeneity and underpinnings of autism.”

The findings align with the idea that rather than being a continuous spectrum, autism has genetically distinct, clinically meaningful subtypes, a notion that Sauerwald and her colleagues also explored in research published earlier this year. “Our work also supported this idea that there’s a difference between late autism diagnosis and early diagnosis,” Sauerwald says. But she stresses that the findings need to be replicated, particularly in diverse populations.

A better understanding of the genetic underpinnings of autism subtypes could also lead to more tailored diagnoses, Warrier says.