Micro-molecules may loom large in autism

The brains of people with autism contain unusual amounts of short regulatory RNAs.

The brains of people with autism contain unusual amounts of short regulatory RNAs, according to the largest-yet study of this kind1. Many of these so-called microRNAs control genes linked to autism.

The findings suggest that tipping the balance among some of the brain’s hundreds of microRNAs may trigger gene expression changes associated with autism.

“There are very widespread changes [in the brain] at multiple levels,” says lead investigator Daniel Geschwind, distinguished professor of neurology, psychiatry and human genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles. The new study represents a comprehensive approach to understanding the molecular changes in the brains of people with autism, Geschwind says. The study appeared 29 August in Nature Neuroscience.

MicroRNAs dampen gene expression by destabilizing messenger RNA, the template for a protein created from a gene. Each microRNA is roughly 20 nucleotides in length, but it can tamp down hundreds of genes.

Geschwind’s team sequenced small RNAs in samples of postmortem brain tissue from 55 people with autism and 42 controls. Previous studies of microRNAs in autism have used fewer samples or focused on a subset of microRNAs, says Peng Jin, professor of human genetics at Emory University in Atlanta, who was not involved in the study.

The data Geschwind’s team collected likely also include information about several other types of small regulatory RNAs that warrant exploration, Jin says. The new work “really provides a very good resource for people studying autism.”

Distinct differences:

Geschwind and his team focused on small RNAs in samples of the cerebral cortex and cerebellum. They identified 699 microRNAs in the samples, 147 of which had not been seen before. They then homed in on 58 microRNAs whose expression is altered in the cerebral cortex of people with autism. Of these, 17 are scarce in autism brains and 41 are abundant.

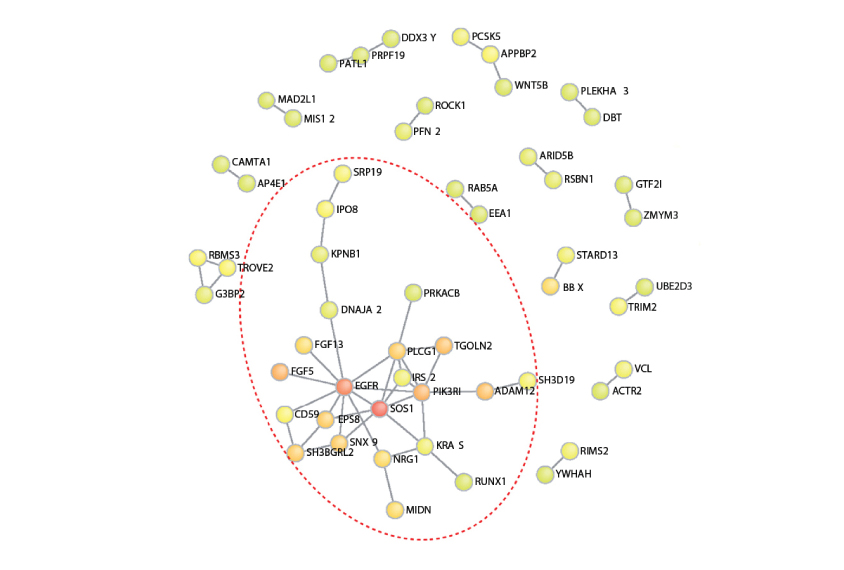

The researchers identified 11 groups, or ‘modules,’ of microRNA that have similar expression patterns across the brains. The microRNAs in two of these modules are relatively abundant in people with autism, and those in two other modules are unusually scarce.

Using an algorithm, the researchers found a large proportion of microRNAs expected to control autism genes in three of the four autism-linked modules.

Gene expression analysis also revealed that the autism brains have depressed levels of genes important for the function of neurons and their connection points, called synapses. Genes involved in the immune system, by contrast, tend to be particularly active in autism brains. These findings are in line with results from a 2011 study by the same team.

Micro modules:

When the researchers explored the relationship between microRNA and gene expression levels, they found that the increase in microRNAs in autism brains tracks with a decrease in the expression of genes specific to neuron function. This result suggests that the elevated microRNAs dampen the expression of these genes.

Similarly, the researchers associated a decline in certain microRNAs in autism brains with an increase in expression of immune genes.

The researchers saw similar changes in gene expression when they increased or decreased the levels of individual autism-linked microRNAs in cultured immature neurons. For example, increasing the levels of miR-21-3p, which is among the most abundant microRNAs in autism brains, dampens genes that are overactive in autism brains. It also lowers the expression of top autism genes, including DYRK1A and PHF2.

These findings solidify the role of miR-21-3p in autism, says Nikolaos Mellios, assistant professor of neurosciences at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, who was not involved in the study. “This microRNA could be a central regulator of many autism genes,” he says.

MicroRNAs are known to also block protein production. Researchers should address whether the autism-linked microRNAs also perturb protein levels, Jin says.

References:

- Wu Y.E. et al. Nat. Neurosci. Epub ahead of print (2016) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025