Researchers advance models of maternal antibody link to autism

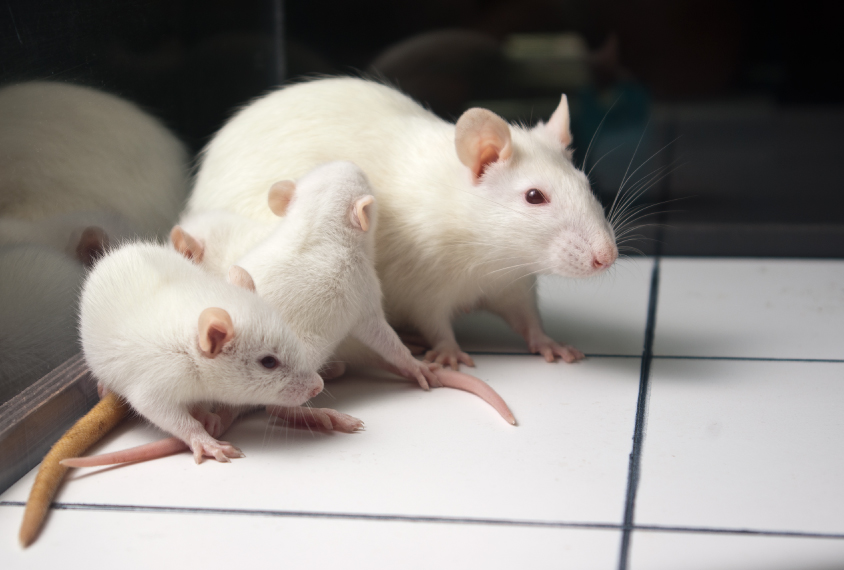

Sophisticated animal models — including a new rat model — are revealing how maternal antibodies contribute to autism risk.

The antibodies in a pregnant woman’s body alter her child’s developing brain: That’s one popular theory for how autism might originate. But exactly how these antibodies change the fetal brain is something of a mystery.

In several posters presented over the past two days at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C., researchers debuted sophisticated animal models — including a new rat model — to study this risk and its interaction with sex.

There is mounting evidence linking a mother’s auto-antibodies — immune proteins that attack the body’s own tissues — to her child’s risk of autism. Mothers of children with autism are more likely to have these antibodies than are mothers of typical children. And some combinations of the molecules may confer a high risk of autism.

Among the new research presented at the conference is one study that explores why boys are more vulnerable to autism than girls are.

In that work, researchers injected pregnant mice with an antibody that targets a brain protein called CASPR2. Mutations in CNTNAP2, the gene that encodes CASPR2, are linked to autism.

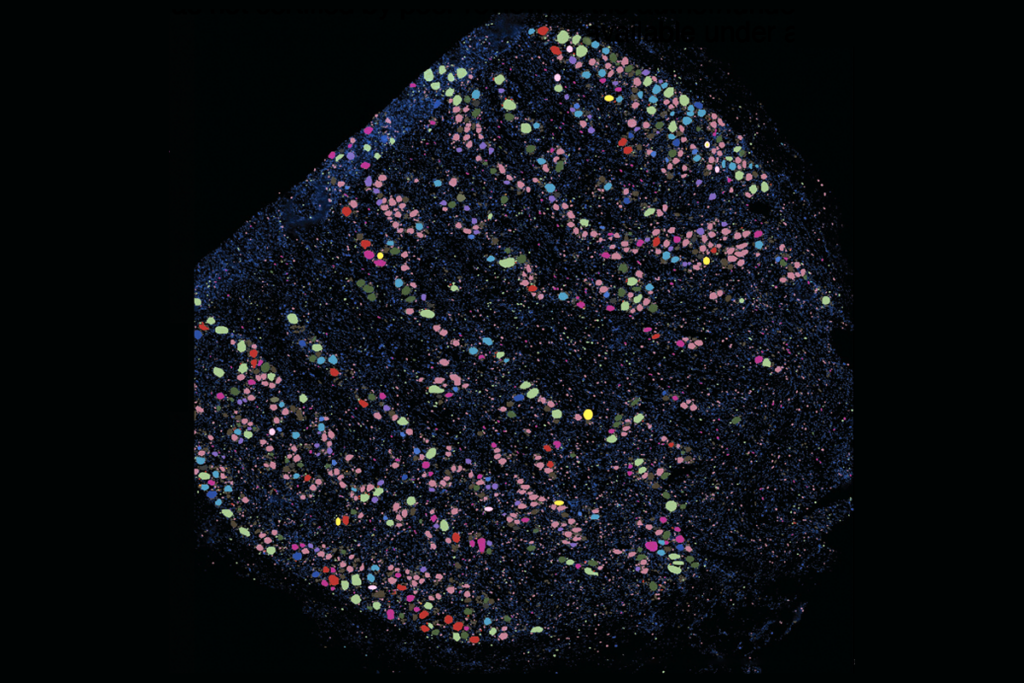

Prenatal exposure to the CASPR2 antibody affects brain development, leading to a thinner cortical plate — a layer of cells involved in the development of the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer rind. It also makes mice less sociable. But these effects occur only in males.

Altered cargo:

To understand this sex bias, the researchers mated female mice with male mice that have an altered SRY gene. This gene governs testosterone production and testes development. In these males, the gene is not on the Y chromosome, its usual home, but on another chromosome.

This meant that the females that became pregnant then carried an unusual litter: normal male and female pups, but also pups with male chromosomes and female hormones, and ones with female chromosomes and male hormones.

“Keeping these genotypes straight is like, whew,” says Adriana Gata-Garcia, a graduate student in Betty Diamond’s lab at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York. Gata-Garcia presented the unpublished findings yesterday.

Fetal mice with male chromosomes and hormones, those with male chromosomes and female hormones and those with female chromosomes and male hormones all have a thinner cortical plate after exposure to the CASPR2 antibody.

This suggests that either male chromosomes or male hormones can make mice susceptible to antibodies’ effects on brain development.

However, only mice with both male chromosomes and male hormones have social impairments after exposure to the antibody. “You need both to be susceptible to the social effects,” says Gata-Garcia.

Cross reaction:

New work is clarifying how auto-antibodies might exert their effects. In findings presented Monday, one group showed that when injected into a pregnant mouse, the antibodies from mothers of children with autism cross the placenta and reach the fetal brain.

“By late gestation, it’s actually sequestering in the fetal compartment,” says Karen Jones, a postdoctoral researcher in Judy Van de Water’s lab at the University of California, Davis, who presented the work. The antibodies remain detectable in the pups after birth.

A fetus would naturally be exposed to these maternal auto-antibodies throughout gestation, however, not just from an injection at a single time point. So researchers are developing animal models in which females produce the antibodies on their own.

Male pups born to mice that produce the CASPR2 antibody show brain abnormalities, including a thinner cortical plate and decreased proliferation of neurons during fetal development, Diamond’s team reported yesterday. The researchers are testing the mice’s social behavior.

Van de Water’s lab, meanwhile, has found that pups of female mice that produce a mix of auto-antibodies are less interested in interacting with other mice than controls are. These pups groom themselves excessively, a trait reminiscent of repetitive behaviors, a feature of autism.

Van de Water’s team has also created a rat model of this effect and shown that the rat pups have the same social deficits and repetitive behaviors. “It’s really exciting that we’re able to replicate this in a cross-species model,” Jones says.

The rodent models may also help researchers explore how to mitigate the harmful effects of the antibodies. Diamond’s group has created a mutated version of CASPR2 that cannot cross the placenta, in order to sop up the harmful antibodies.

“We want to find a way to capture antibodies in the mom so that it doesn’t get to the fetus,” says Lior Brimberg, assistant professor in the Center for Autoimmune and Musculoskeletal Disorders at the Feinstein Institute.

The researchers plan to test whether giving pregnant mice the mutant CASPR2 can prevent harmful effects in their pups.

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models