Spotted: Rebranding oxytocin; marsupial madness

The ‘love hormone’ oxytocin needs a scientific makeover, and left-handed kangaroos don’t have autism.

- Some people call it the ‘love molecule’; others prefer ‘cuddle hormone.’ There’s no shortage of warm, fuzzy nicknames for oxytocin, but what autism researchers really want is hard science.

An article published this week in Nature suggests the old hormone needs a new shtick — a rebranding of sorts. “It doesn’t induce love; it doesn’t induce massive amounts of trust,” Adam Guastella, clinical psychologist at the University of Sydney, told Nature. “The sorts of biology we’re studying here are incredibly complex.”

Trials testing the hormone’s effects in people with autism have been inconclusive. That’s why researchers are taking a step back trying to truly understand oxytocin’s effects in the brain. For more about the molecule’s lingering promise, check out our Q&A with oxytocin pioneer Larry Young, director of the Silvio O. Conte Center for Oxytocin and Social Cognition at Emory University in Atlanta.

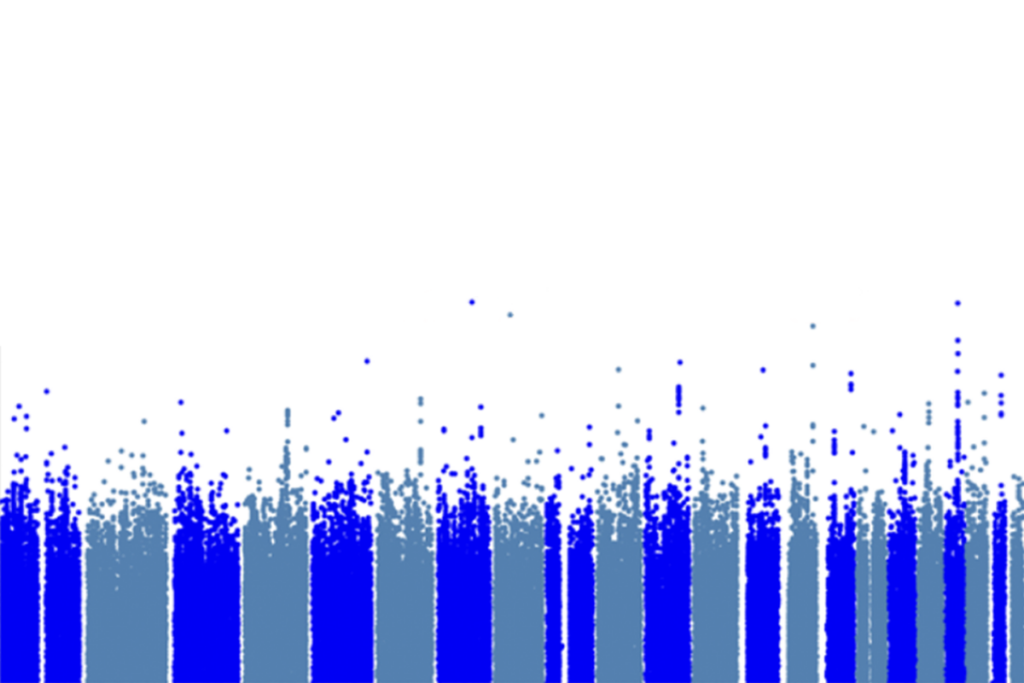

- Stanford University has received a $9 million grant from the Hartwell Foundation to establish the world’s largest autism database. Dubbed iHART, for the Hartwell Autism Research and Technology Initiative, the database will house genetic, brain imaging and behavioral information about 5,000 individuals with autism. Best of all, it’s open-access, meaning users are free to tap the data for their own research needs.

- Retractions are getting more attention than they used to. Whether they stem from honest mistakes or full-on fraud, they must damage a researcher’s credibility, right?

An article published this week in Science looks at the extent of that damage. Citing a May report by theNational Bureau of Economic Research, the article says bigwig biomedical scientists see a 10 percent dip in citations of past papers after an ‘honest mistake’ retraction. This dip swells to 20 percent after misconduct.

The citation hit is a penalty, “but it’s not a death sentence,” John Walsh, professor of public policy at the Georgia Institute of Technology, told Science. “One way to think about it is you can survive a scandal.”

- Speaking of fraud, an article published this week in Poynter looks at the growing role of rumor websites in uncovering scientific misconduct. One such site, PoliSciRumors.com, documented rumblings of foul play on the infamous gay marriage study almost six months before the high-profile retraction by Science, according to the article.

- An op-ed by Emily Willingham that Forbes published this week highlights the hazards of press releases — the short blurbs journals and institutions send out to summarize important studies. In theory, they give journalists a rundown of the study’s implications. But they can be misleading.

Case in point: A press release issued last week by Current Biology suggested that studying left-handed kangaroos may shed light on autism. Autism is never mentioned in the study, but several news sites that covered the study highlighted the connection. One article even stated that “autism is widespread among kangaroos.”

“I have seen autism attributed to animals from mice to horses to cats, but kangaroos? That’s a first,” Willingham wrote, stressing that autism is, by definition, a human disorder.

The mistake serves as a valuable reminder of the importance of clear, correct communication between scientists and the public.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects