Studies send mixed messages on antidepressants’ link to autism

Four large studies published since May arrive at various conclusions about whether exposure to antidepressants in the womb ups autism risk.

Antidepressants slightly boost the risk of autism and other brain conditions. Or they don’t, and it’s really factors related to the mother’s mental health that pose the risk1,2,3,4.

That’s the confusing upshot from four large studies published since May, all looking at the effects of exposure to antidepressants in the womb.

“The challenge for all studies in this area is that regardless of various statistical analyses and study designs, we struggle to fully understand what effect the underlying maternal mental disorder has on the outcome,” says Trine Munk-Olsen, an epidemiologist at the National Centre for Register-Based Research at Aarhus University in Denmark who led one of the studies.

The studies represent increasingly sophisticated efforts to separate the effect of antidepressants from that of depression itself. All are based on data from Sweden and Denmark, countries that have universal healthcare systems and databases of birth and medical records.

“These are certainly adding to our understanding” of the relationship between antidepressants and autism risk, says Brian D’Onofrio, professor of psychological and brain sciences at Indiana University in Bloomington. D’Onofrio led an earlier study on the topic but was not involved with any of the new work. “Unfortunately, we’re just not getting a perfectly clear message.”

What is clear, the experts say, is that even if maternal antidepressant use does raise the chances of autism in a child, the risk is extremely small.

Careful controls:

Some studies have compared women who took antidepressants during pregnancy with women who did not — but many, if not most, women in the latter category were not depressed. This design leaves open the possibility that some other factor related to maternal depression influences autism risk.

To bypass this problem, one of the new studies has a control group of women with conditions such as depression or anxiety — but who did not take antidepressants during pregnancy.

The comparison revealed that antidepressant use during pregnancy may result in a small but real increased risk of autism, especially autism without intellectual disability1.

Among the 254,610 children living near Stockholm, Sweden, included in the analysis, the rate of autism is 2.9 percent for children whose mothers have a psychiatric condition but did not use antidepressants during pregnancy. By contrast, it is 4.1 percent for those exposed to antidepressants in the womb. (The rate is 2.1 percent for children born to women with no history of mental illness.)

When the researchers homed in on sibling pairs in which one child has autism, they found a slightly increased incidence of antidepressant use by the mothers when they were pregnant with the affected child.

Subtle signs:

A second study, led by Munk-Olsen, yielded similar findings2. It is the first large study to examine associations between maternal antidepressant use and a range of psychiatric conditions in the child. These include autism as well as mood disorders.

The researchers assembled data on more than 900,000 children born in Denmark between 1998 and 2012, including 32,400 who received a psychiatric diagnosis. They found that 8 percent of children whose mothers never took antidepressants have a psychiatric condition. That rate jumps to 11.5 percent if the mother stopped taking antidepressants during pregnancy, and to 13.6 percent if the mother took the drugs throughout pregnancy. It is highest, at 14.5 percent, among children whose mothers started taking the meds during pregnancy.

The results suggest that prenatal exposure to these medications boosts the risk of psychiatric conditions.

“These [study] designs are helping us to do a better job” of isolating the effects of depression from those of its treatment, D’Onofrio says, but they have their own limitations and confounds. For example, taking antidepressants while pregnant may be a marker for severe depression, which may raise the child’s risk of certain conditions.

Children whose fathers took antidepressants around the time of the mother’s pregnancy are also at elevated risk of a mental health condition, the researchers found. But this effect is less than that from the mother. The Stockholm study, by contrast, found no increased risk of autism from a father’s antidepressant use.

Vanishing link:

The two other studies took a different approach: They compared pregnant women who took antidepressants with those who didn’t, and then used statistics to account for possible effects on autism risk from a broad range of mental health conditions — instead of simply looking at whether the mother has a psychiatric history overall.

“We applied a very detailed adjustment for psychiatric history of the parents,” says Sven Sandin, a statistician and epidemiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, who led both studies.

Sandin and his colleagues examined data from 179,007 children born in Sweden in 2006 and 2007 and followed them until they were 7 or 8 years old. Of these children, 3,982 were exposed to antidepressants in the womb, and 1,641 are diagnosed with autism.

The researchers found an association between maternal antidepressant use and autism risk, but it disappears once they account for parents’ psychiatric history. When they restricted the pool of mothers to those with a history of depression or anxiety, they again did not find a significant effect of antidepressants on autism risk3.

The team then reanalyzed the data, this time looking at the link between maternal antidepressant use and intellectual disability4. They found an increase in risk of intellectual disability associated with antidepressant use, but the association is not statistically significant after adjusting for the mother’s mental health, among other factors.

The results are broadly consistent with those from a trio of studies published earlier this year. In those studies, the autism risk associated with maternal antidepressant use disappeared once scientists accounted for confounding factors such as the mother’s mental health, age and education. (Those studies did not look at intellectual disability.)

Ultimately, getting a definitive answer from large epidemiological studies is difficult, experts say. Small studies that meticulously track parents’ psychiatric histories and antidepressant use, as well as animal studies, could fill in the picture.

References:

Recommended reading

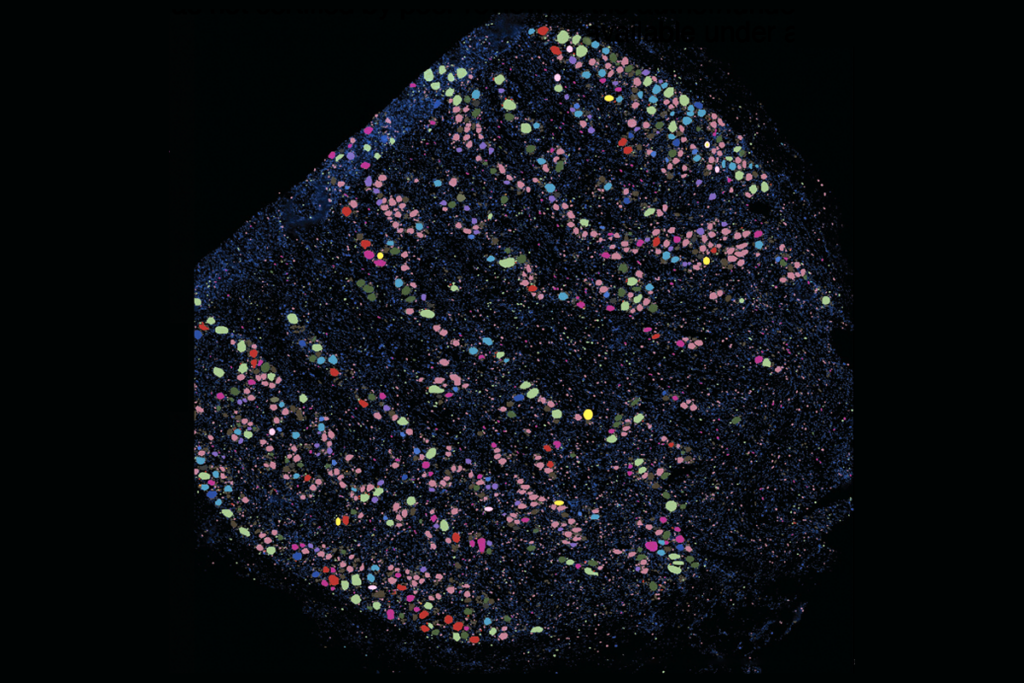

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models