What matters for protein linked to autism? Location, location, location

One form of the protein implicated in Angelman syndrome and autism clusters in the nucleus, and it’s this form that may be critical to brain development.

One form of the protein implicated in Angelman syndrome clusters in the nucleus of the cell, and it’s this form that is critical to brain development, a new mouse study suggests1. The results point to a new path forward for studying the syndrome, which shares its roots with some types of autism.

Angelman syndrome results from either loss of or mutations in the maternal copy of the gene UBE3A, which encodes an enzyme that tags proteins for degradation. But it’s unclear how the mutations lead to the condition’s hallmark traits, which include developmental delays, problems with speech and movement and, often, autism.

The new study suggests researchers might look to the nucleus to find out.

“We only recently found that there are a lot of UBE3A proteins in the nucleus,” says Ype Elgersma, professor of molecular neuroscience at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, who co-led the study.

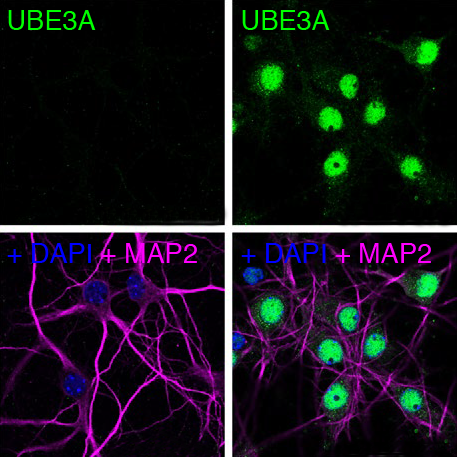

UBE3A makes two forms of the same protein — a short form found in the nucleus and a longer one in the cytoplasm. Elgersma and his colleagues showed that most of the protein in neurons is the nuclear form.

The team made two different sets of mice: one with UBE3A only in the nucleus and another with it only in the cytoplasm. Mice with the protein only in the cytoplasm spent more time floating in water as opposed to swimming, used fewer materials when building a nest and buried fewer marbles than either the mice with only nuclear protein or controls — behaviors similar to those seen in mouse models of Angelman syndrome.

“When the first behavioral results came in, I was completely shocked. Nobody could have predicted it, not even me,” Elgersma says. “We are the first ones to show that the nuclear location is very important.”

Seeing the invisible:

The sheer abundance of UBE3A in the nucleus also came as a surprise to the team.

The researchers looked at the distribution of the protein’s two types in the mouse hippocampus, human stem cells and postmortem tissue from the human prefrontal cortex. In all three, the short form in the nucleus accounted for 70 to 80 percent of total protein.

They also confirmed that UBE3A’s absence in the nucleus disrupts the balance between excitatory brain signals and inhibitory ones — similar to the imbalance seen in mouse models of Angelman syndrome. The results were published in June in Nature Neuroscience.

“I am excited about their results. I do like to think that nuclear form is probably the most relevant to social behavior,” says Janine LaSalle, professor of medical microbiology and immunology at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the study.

The focus on UBE3A’s location in the cell opens new avenues for research, others say.

“I think it’s an interesting hypothesis and it’s a great experiment. It gives new perspective, and maybe we should be thinking about those things that are in the nucleus,” says Seth Margolis, associate professor of biological chemistry at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

Because the nucleus contains most of the UBE3A protein, he says, it’s still unclear whether the mice’s behavioral traits arise from a lack of nuclear UBE3A or just less protein overall.

References:

- Trezza R.A. et al. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1235-1247 (2019) PubMed

Recommended reading

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

AI-assisted coding: 10 simple rules to maintain scientific rigor

Frameshift: Shari Wiseman reflects on her pivot from science to publishing