Why autism research needs more input from autistic people

Too many scientists fail to acknowledge autistic people’s potential contributions to the field. This shortsightedness damages scientists’ ability to help people.

I am a student and researcher studying evolutionary genetics, and I am autistic. I often come across papers on autism research, but unfortunately, reading them is rarely a positive experience.

Too much autism research fails to acknowledge autistics as people who can read and make valuable contributions to the field. Instead, it casts them as little more than passive study participants or recipients of treatment. This shortsightedness damages research and scientists’ ability to help autistic people.

Reading autism research as an autistic person can feel like being treated as an alien. For example, consider a 2019 paper that stated: “This finding reinforces other work which shows that autistic people can have, maintain, and value close romantic relationships and friendships.” Imagine how bizarre it would be to read that about yourself.

I do not mean to pick on that paper in particular, but on a research culture in which anyone would think that sort of statement needs to be made.

This sort of culture results in seeing top researchers throw around blatantly wrong and offensive ideas about my community. For an old but powerful example, British researcher Simon Baron-Cohen endorsed a quote that suggested autistic individuals experience people at dinner parties as “noisy skin bags” that are “draped over chairs.” In my view, the appropriate response to that is, “No, that is absolutely not how we experience anything. What the hell?” Of course, that would not be an appropriate academic reply.

I understand that even seemingly obvious things need to be examined and tested in science, but if someone were to suggest that the moon is made of cheese, I doubt researchers would insist on disproving it with a study. Yet somehow autistic people must be so strange and unknowable to researchers that they cannot dismiss equally implausible characterizations of us.

In fact, many autistic people are available to answer questions about how we see things. Many of us speak up and share our stories proactively. It can seem to us as if scientists are not listening.

Then there are papers that suggest society would rather fewer people like me existed — and not because they care about my suffering. Or those that survey the prospects of preventing autism, pointing out that these are “high priorities for researchers, parents, advocates, clinicians, and educators.” Why is there is no mention of autistic people on that list?

Integration barriers:

The opportunities for someone like me to correct the culture in autism research are limited.

Often when I see these things in the course of my work, I just sigh and ignore them. If I’m discussing a paper with my scientific peers, I do not want to bring up issues with the paper’s treatment of autism and be seen as an ideologue, research subject or object of pity rather than as a respected colleague.

Other people’s responses can also thwart meaningful exchange. Last summer, I ‘came out’ as autistic while in conversation with an autism researcher and several of her colleagues. The people in the group responded with something along the lines of, “Oh, well, you’re not like other autistic people, so those points do not apply to them.”

If a person’s ability to converse with you makes you assume she is not like ‘real autistics,’ then your idea of autism is automatically going to be ‘people who can’t talk to me.’ You will have a flawed understanding of autism and may not be able to see autistic people as potential colleagues. This risks researchers perceiving autistic people purely as research subjects who do not talk back, have opinions or contribute to the process.

Autistic people are treasure troves of information on their own lives. By including more autistic voices in research, we as scientists could improve our ability to gather knowledge about the condition.

Given the flaws in prevailing theories of autistic psychology, I believe we should encourage more qualitative, open-ended research that seeks input from autistic people and establishes a firmer basis for future studies. We could also seek their help in prioritizing treatment targets. Likewise, if biomedical researchers are going to get funding for studying autism, they must make more of an effort to engage with the autistic community and their wishes.

Things are getting better, and many researchers are doing good work. But listening to autistic people could help them make faster progress. Autistic people are not aliens with whom scientists cannot communicate. We are right here. We are reading what you have to say, and that communication can go both ways.

Elle Loughran is a Laidlaw scholar studying genetics at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland.

Recommended reading

How pragmatism and passion drive Fred Volkmar—even after retirement

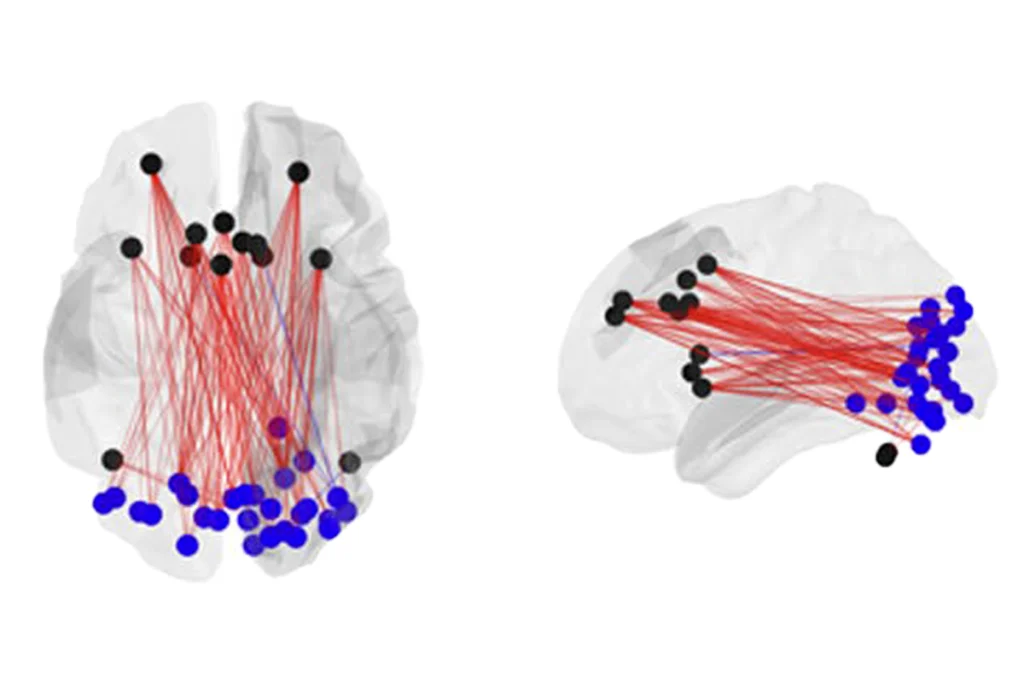

Altered translation in SYNGAP1-deficient mice; and more

CDC autism prevalence numbers warrant attention—but not in the way RFK Jr. proposes

Explore more from The Transmitter