Retraction, She Wrote: Dorothy Bishop’s life after research

A renowned researcher’s eye for detail has given her a second career and a new following.

Last year, when Dorothy Bishop wanted to figure out how six suspicious-looking manuscripts had all been accepted for publication in the same psychology journal, she decided to set up a sting operation.

By that time in her career, after five decades as a psychology researcher, Bishop had seen quite a few questionable papers and thought a great deal about the differences between deception, fraud and honest mistakes. These manuscripts in particular carried a whiff of fraud. Sometimes manuscripts are found to contain “tortured phrases” — sets of words created by running someone else’s writing through a synonym finder in the hope of masking plagiarism. Such phrases are often hallmarks of manuscripts generated by paper mills, shadowy organizations that sell these manuscripts to researchers and then place the papers in academic journals.

But these papers had different issues that hinted a paper mill. The authors had supplied email addresses with country domains that did not match their academic addresses, and the findings in the papers were weakly supported. Bishop could not fathom how the papers had passed a rigorous peer review.

The papers were published in the Journal of Community Psychology, and to Bishop that meant the editor-in-chief either had not noticed the poor quality of the papers or he was complicit. Bishop and her colleague Anna Abalkina, who initially flagged these papers for Bishop, wanted to test the journal’s editorial process, so they submitted a manuscript about the six suspicious papers. And then they waited.

The editor rejected their manuscript because of “superficial analysis,” Bishop says, which was “not what I expected at all.” The sting had failed, and she never got her answers. Still, the six articles were later retracted, and for Bishop that had to be satisfaction enough: A scientific wrong had been righted.

The sting shows how far Bishop is willing to go in her fight to keep the science world clean, but she had been investigating questionable research practices for a while by then: In 2015, she helped convene a workshop on reproducibility in research that later grew into the UK Reproducibility Network, and over the years, she has questioned the integrity of numerous papers.

Uncovering fraud and challenging sloppy science might seem exciting, but Bishop understands it is not something that should be taken lightly. Some science sleuths “get a kick out of” this work, she says, but “I definitely don’t. I always feel a bit sorry” for exposing people, for making them clarify, respond or retract.

B

ishop grew up in East London, England, in a “grotty” suburb called Ilford. Her father settled there after returning from World War II in Germany, where he’d met a woman, Annemarie, who already had a child from a previous relationship. He brought them both back to England and received a cool reception. There was anti-German sentiment in the country, so that was part of it, Bishop says. But also, her grandparents likely were “shocked” when their son came back from the war with a woman and small child in tow. The couple married anyway and had two more children: first a boy, and then Dorothy in 1952.

Bishop’s father spent his post-war career in the family furniture shop, but her mother went to night school and taught German to businessmen. Of her two parents, Bishop says, it was her mother who had the academic pedigree. Bishop’s maternal great-grandfather, Rudolph Eucken, won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1908, and her grandfather, Arnold, was a noted chemist. But Bishop’s mother was estranged from her parents, and Arnold died by suicide two years before Bishop was born. Her grandfather had struggled, she was told, with the loss of his son, who had died on the Eastern Front in the war. But Bishop also says she wonders if he was burdened by his involvement in the Nazi Party — her mother had always said he never joined, but the internet suggests otherwise.

The only family member Bishop knew on her German side was her Aunt Margaret, a brilliant chemist who worked in industry because academia “wasn’t the place” for women back then, Bishop says. In her own schooling, Bishop was often bored, but she knew she wanted to go to university and indeed was accepted to the University of Oxford. She began her undergraduate work in 1970 at St. Hugh’s College, one of the five colleges at Oxford that accepted women at the time. Originally, Bishop had planned on degrees in physiology and philosophy, but tutors suggested psychology to her, and she gave it a try. She earned her degree in experimental psychology in 1973 — at the time a brand-new degree at Oxford.

After that, she did a two-year clinical course in psychology at the University of London. These were the earliest days of cognitive behavioral therapy, but Bishop didn’t feel like a “natural” clinician, she says — good, but not great. So she packed up and headed back to Oxford.

There were two reasons for that. First, she felt more research needed to be done before anyone could be truly helped. Second, Patrick Rabbitt was at Oxford. He had taught her during her undergraduate years, but she had seen him around a few times since, and something new was forming. They had “a deep understanding” of each other, she says, “which was there right from the outset.” Bishop started her Ph.D. in 1975 in the lab of neuropsychologist Freda Newcombe, and she married Rabbitt, a cognitive gerontologist, in 1976.

N

ewcombe had risen to prominence after World War II, studying language loss in men who had sustained massive head injuries in battle, and Bishop expected to work in the same area. But a new residential school for children with language and communication disorders, called the Dawn House School, had recently opened, and Newcombe was asked to come take a look.Bishop tagged along on a visit, and once she dipped her toe into the work at the school, she was hooked. The research on communication disorders in children that she started there would come to define her career.

One early goal was to categorize the children into specific “bins” with named communication disorders, but this task proved difficult. The literature at the time, Bishop says, was jumbled, and it felt like a variety of disorders were being lumped together. She developed an assessment test and administered it to the school’s children. When it was put to use, it became clear that, as far as communication disorders go, the group was “completely heterogeneous.” Bishop called this the Test for Reception of Grammar, and it is still in use today.

The prevailing notion at the time was that language difficulties in children were the result of poor parenting. But when Michael Rutter’s landmark 1977 twin study showed a genetic component to autism, Bishop wondered if problems with language development were genetic too.

She started up her own twin study, calling schools to ask about both identical and non-identical twin pairs. Her conclusion was that identical twins with language issues were much more similar to each other than were non-identical twins. There was a genetic component to these communication struggles, she realized. Bishop published a pioneering paper on this in 1995, helping to form a foundation that other researchers would continue to build on.

The connection of speech and language impairment to genetics was “kind of a game changer,” says Courtenay Norbury, one of Bishop’s former doctoral students, now professor of communication disorders at University College London. Bishop “truly was one of the first experimental psychologists who could see the value of behavioral genetics,” Norbury says.

But Bishop never stayed in one place long. Rabbitt moved from job to job, and she often went with him, though sometimes she and Rabbitt lived in different cities as one job ended or another began. She did research at Newcastle University, the University of Manchester, the University of Cambridge and then Oxford again, all the while working to untangle the mechanics of developmental language disorder. She also developed additional assessments, such as the Children’s Communication Checklist-2, that are still in regular use.

If, early in her career, Bishop had thought she might find singular causes for certain communication disorders, she came to understand that this thought was “naive.”

“Language is a vulnerable cognitive function,” she says. “You can have many paths that will lead to a language disorder.” The diagnostic categories and groups people are placed into are “just artificial abstractions humans use to try and make sense of the world,” she says. The reality is “much messier and sloppier,” and the goal should be getting services to those who need them.

I

n 2010, Bishop joined Twitter. When she realized she had more to say about research, life and everything else than she could squeeze into 140 characters, she started the BishopBlog. She was active online (to date she has tweeted more than 84,000 times) and incisive, and she built a loyal following.In early 2015, she received a tip on Twitter about a journal editor and autism researcher named Johnny Matson at Louisiana State University. Matson cited himself quite a bit and also published his own papers in the journals he edited. Bishop found this unseemly and posted an analysis on her blog, diving deep into Matson’s publishing habits. She revealed three other editors along with Matson who may have been getting their own papers published quickly by submitting to journals where they were all editors. She received some scathing anonymous comments on her blog post that questioned her motives, but the posts were picked up by large news outlets, and she was vindicated in 2023 when two dozen of Matson’s papers were retracted.

Matson’s retracted work was not shown to be fraudulent, and most of it was not well cited, so at times Bishop wonders if the results are worth the effort. But her work has a greater mission. When she shone a light on the paper mill that provided the fraudulent manuscripts to researchers for the Journal of Community Psychology, in part she wanted to separate the bad apples from the bushel. These transactions occurred between researchers and paper mills in post-Soviet countries, and Bishop feels “very strongly that if your country is identified as a country full of fraudulent paper mills, it’s really bad for the honest people in that country.” If a few sloppy papers go unnoticed or a few unethical editors are allowed to slide, it has a domino effect on the whole community, she says. That’s what she’s here to fight against.

When Bishop retired last year, her former trainees threw a two-day celebration at the Royal Society in London in her honor. At 70, she felt it was time to go. “I just don’t want to be one of these people that goes on and on,” she says. One reason is that she wants to make way for a new generation. Bishop has always been gracious to trainees, Norbury says. But she also wants to spend more time at the cinema and exploring local history, maybe doing some photography. She still makes rounds at conferences, talking about problems in publishing. She is also serving as another kind of mentor, helping her husband craft his Substack so he can self-publish his memoirs of growing up in colonial India.

And she writes creatively herself. She wrote and self-published a five-part series of mystery novels called “The Fremantle Mysteries.” The protagonist seems a lot like Dorothy Bishop, except she solves murders. In fact, the books read a bit like Agatha Christie novels. She finished that series in 2017, and these days Bishop sometimes strolls the historic streets of Oxford, taking photographs or puzzling through her own “cases” of academic fraud. The recognition for her sleuthing keeps coming. Just last month, she was featured prominently in a report on reproducibility and research integrity for the U.K. Parliament. Earlier this year, you could hear her talking about scientific malpractice on The Economist podcast and BBC Radio.

This is Bishop’s second act — one centered on sleuthing. A hobby she thought she could dabble in during her retirement has expanded to fill most of her days, she says — an unsurprising development to those who know her. Norbury, who describes Bishop as the “quintessential scientist,” says that no matter what issue Bishop tackles, “she just wants to know the truth.”

Correction

Recommended reading

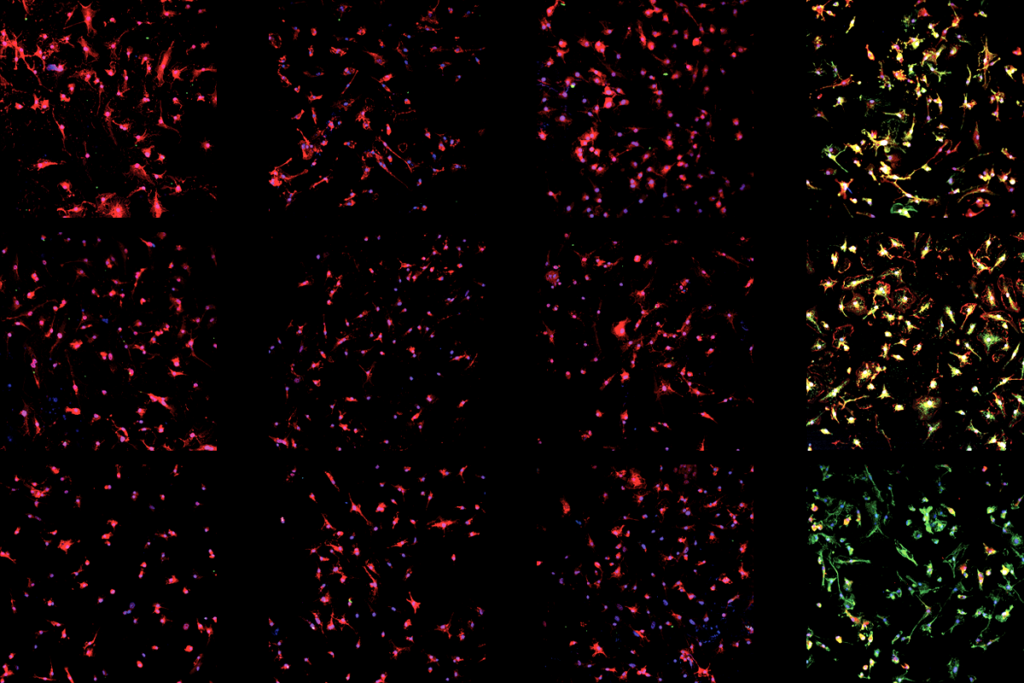

Authors correct image errors in Neuron paper that challenged microglia-to-neuron conversion

Exclusive: Issues with dozens of papers prompt inquiry into prolific stroke researcher

‘Spoonful of plastics in your brain’ paper has duplicated images

Explore more from The Transmitter

Machine learning spots neural progenitors in adult human brains

Xiao-Jing Wang outlines the future of theoretical neuroscience