Eight mental health conditions occur unusually often in autistic people, a new analysis of 96 studies suggests1.

Certain mental health conditions are known to accompany autism, but estimates of their prevalence in autistic people vary widely2.

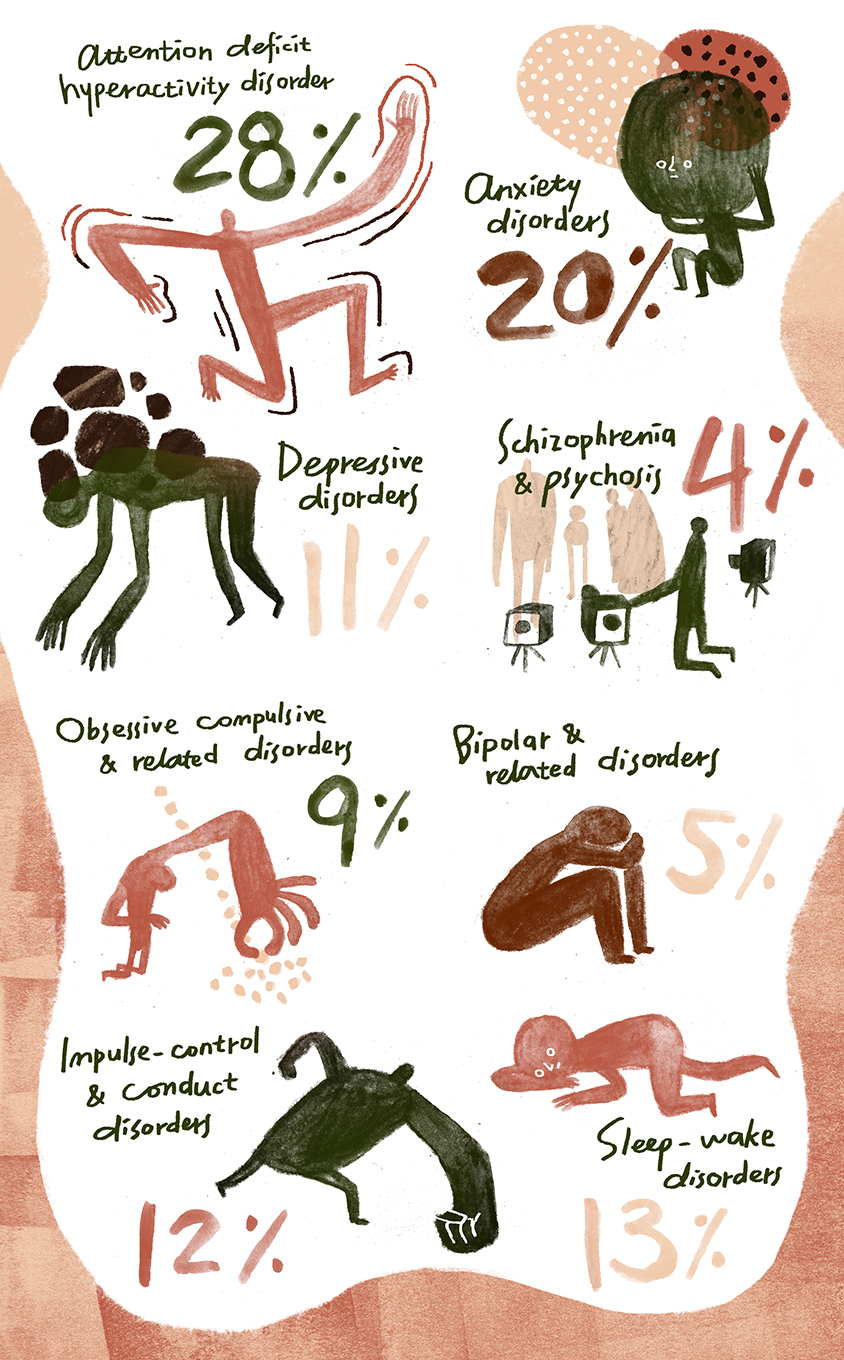

The new study establishes prevalence by pooling data from the studies and conducting a separate statistical analysis for each set of conditions: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, impulse-control and conduct disorders and sleep-wake conditions. The prevalence of these conditions was consistently elevated in autistic people.

“It gives us a more holistic picture of the increased rates across the board in terms of major and common mental health conditions,” says lead investigator Stephanie Ameis, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto in Canada. It also shows that the prevalence of three of the conditions — depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia — increases with age.

Ameis and her colleagues screened nearly 10,000 studies published from January 1993 to February 2019 that included diagnoses of mental health conditions among people with autism. They discarded studies with fewer than 20 autistic people and studies in which diagnoses had not been made using criteria in either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases.

They then culled studies in which researchers asked about mental health conditions over a lifetime, because these lack data on age of diagnosis, which Ameis and her colleagues wanted for their analysis. Results from the final 96 studies appeared in August in Lancet Psychiatry.

ADHD is the most common mental health condition in people with autism, occurring in 28 percent. The next most prevalent is anxiety, which affects 20 percent. However, the analysis does not explain why these conditions occur at high rates in autistic people.

“This study highlights the gaps in our current knowledge of co-occurring conditions in autism,” says Tara Chandrasekhar, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development in Durham, North Carolina, who was not involved in the study.