Why autism remains hidden in Africa

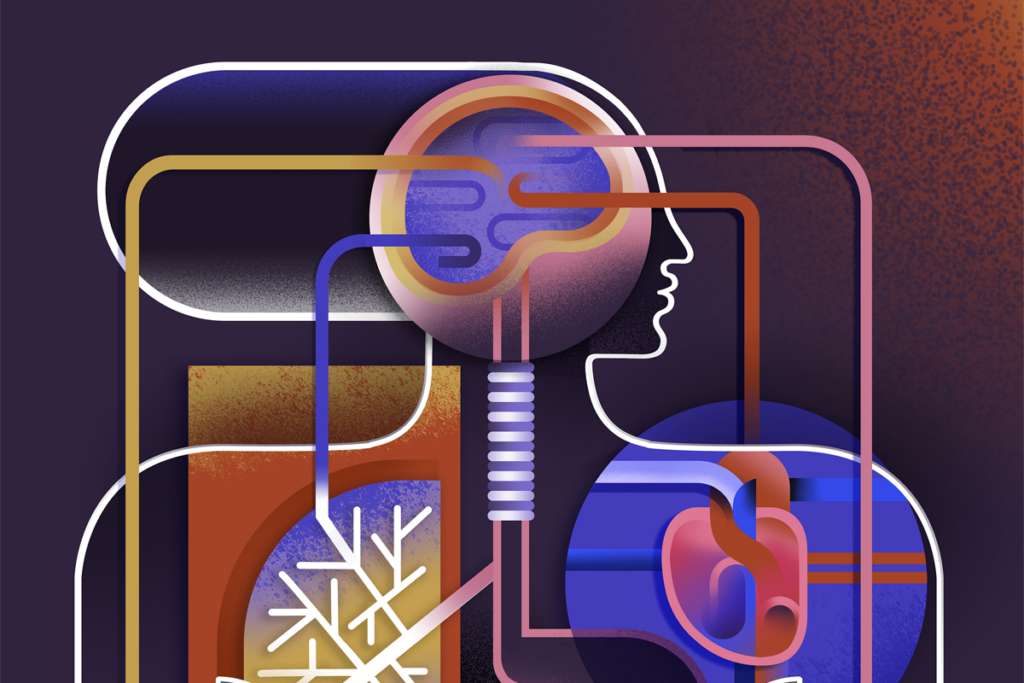

Many African children with autism are hidden away at home — sometimes tied up, almost always undiagnosed. Efforts to bring the condition into the open are only just beginning.

T

he 8-year-old girl’s head drooped like a wilted flower as she sat slumped in a wooden chair in her neighbor’s kitchen. Her wrists were swollen from the dingy white shoelace that bound them behind her back. The girl’s mother, Aberu Demas, wept as she untied her child.Earlier that day, Demas had arrived unannounced at the Joy Center for Autism in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. A single mother living on the outskirts of town, Demas didn’t know what autism was or if her daughter, Fekerte, had it, but she was desperate for help. Fekerte could not speak or feed herself, and Demas had no family or friends to look after the girl when she needed to work or run errands. Afraid that Fekerte would wander off and drown in the river behind the houses, Demas felt she had no choice but to tie her up.

It had taken Demas about an hour to get to the center by bus. And because she didn’t have an appointment, she had to wait about three hours until Zemi Yenus, the center’s founder, could see her. The center was at maximum capacity, so when they finally met, Yenus told Demas she could only put Fekerte on the waiting list. Demas began to cry, and confessed that she had left her daughter tied up and alone.

Yenus did a quick calculation: By the time Demas got home, Fekerte would have been restrained for at least six hours, with no food, water or bathroom breaks. That was the end of the meeting: Yenus immediately drove Demas home to free Fekerte, and reassured the woman that she would make room for the girl at her school. Fekerte wasn’t the first child Yenus had seen in that state — or the last.

In the 10 years since then, Yenus says she has encountered hundreds of children locked away or tied up — although the situation has improved slightly. Like Demas, many parents resort to these extreme measures because they have no other choice. Others hide their children, fearing stigma, which is pervasive in many parts of Africa and casts disabilities as the sign of a curse or possession by a spirit.

Many children with autism across Africa stay out of sight for another reason: Few clinicians have the skills or experience to identify the condition, if they are even aware that it exists. In all of Ethiopia, with its roughly 100 million inhabitants, there are about 60 psychiatrists, and only one who specializes in child psychiatry. Only two public clinics provide child mental health services, and both are located in Addis Ababa, where a small fraction of the population lives (a scant 15 percent of Ethiopians live in cities). In 2015, there were about 50 child and adolescent psychiatrists for the 1 billion or so inhabitants of sub-Saharan Africa.

Yenus, whose adult son was diagnosed with autism in England, is a beautician by training, but she has made informal diagnoses for many children in her care, including Fekerte. She founded the Joy Center, the first of its kind in Ethiopia, in 2002. She and other parents of children with autism have spent the past 20 years or so trying to raise awareness of autism in Africa. With little guidance available to them, they have also resorted to creating their own treatments to help children on the spectrum learn to communicate and master basic skills. None of these homegrown therapies have been validated, but these families simply cannot afford to wait. “I’m not saying we don’t need that, but that’s not what we need right now,” Yenus says. “What I need is to free more children, educate parents and other educators.”

The help these families need has been slow to come, but researchers are beginning to pick up the pace. Some are tailoring diagnostic methods and treatments for African populations and devising ways to reach rural communities faster. In September, the International Society for Autism Research held a meeting in South Africa — the first of its kind on the continent — to highlight research there. Around 300 researchers, therapists and family members from more than 25 countries, mostly African, met for the first time at the three-day event. “My hope is that this will not be a one-off event, but the start of an ongoing process of building networks and connections within Africa,” says conference co-organizer Petrus de Vries, Sue Struengmann Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Cape Town. Even the wealthiest parts of Africa have a long road ahead, however. “What we have here [in Cape Town] may probably be as good as it gets in Africa,” de Vries says. “And yet our services for people with autism are almost nonexistent.”

”“I have not come across any indication that there’s anything different about the presentation [of autism in Africa].” Amina Abubakar

Missing children:

V

ictor Lotter, a researcher at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, published some of the first descriptions of people with autism in Africa in a 1978 paper. He screened more than 1,300 children at institutions for people with intellectual disability in six African countries; he found 9 children who qualified for a diagnosis and 30 others with features of autism. Lotter reported that, as with children he had studied in the United Kingdom, autism in Africa appeared more often in boys than in girls. But compared with their British peers, African children with the condition were less likely to show repetitive and stereotyped behaviors.It was a promising start. But “since then, not much has happened,” de Vries says. This year, he and his colleagues laid out all of the peer-reviewed studies ever published about autism in the 46 countries of sub-Saharan Africa. They found only 53 analyses, from just nine countries. About 80 percent of the studies focused on South Africa and Nigeria, two of the wealthiest countries on the continent.

Their analysis did not support Lotter’s claim: The studies found that autism is fundamentally no different in Africa than it is anywhere else in the world. Researchers in Kenya had reached the same conclusion after a similar review the year before. “Personally, I have not come across any indication that there’s anything different about the presentation [of autism in Africa],” says Amina Abubakar, a research fellow at the Kenya Medical Research Institute in Kilifi, who led the Kenyan analysis.

The biggest differences are who gets diagnosed and when. Children with autism in Africa tend to be diagnosed around age 8, about four years later, on average, than their American counterparts. More than half of African children with autism are also diagnosed with intellectual disability, compared with about one-third of American children on the spectrum. This suggests that only the most severely affected children are being picked up: Those who are diagnosed often speak few or no words and require substantial help with everyday tasks such as eating or going to the bathroom. By contrast, in the United States, the largest diagnostic increases over the past few decades have been on the milder end of the spectrum.

These findings seem to be in line with the belief that autism is more severe in African children than in children elsewhere. However, the studies that offered up this idea were small — the largest included only 75 participants. And they focused predominantly on children brought to neurology or psychiatry clinics. “The children who end up there are almost by definition the more severely affected kids,” de Vries says.

In 2012, de Vries returned to South Africa to set up the continent’s first autism research program and to better understand what the condition looks like there. “My simple thought was, ‘Okay, we’re going to start with a prevalence study, then we’ll know what we’re dealing with.’” But he quickly realized that reliable prevalence estimates would need reliable diagnoses — and those were not easy to come by in Africa, where diagnosis is often based on judgment calls by people with little to no experience or expertise in autism.

So de Vries took a step back to focus on diagnosis first. One strategy is to adapt the ‘gold-standard’ diagnostic tools developed in the U.S. and the U.K. — the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) — for use in Africa. It’s unlikely that either test will be routinely used in Africa any time soon. Both tests are too expensive for that, and de Vries is also the only person in all of Africa who knows how to train others to use either one. He has translated the ADOS into Afrikaans, one of the 11 official languages spoken in South Africa, and is validating it for use. Abubakar and others have translated the ADOS into Kiswahili, one of Kenya’s two official languages. But there are about 2,000 languages spoken across the continent.

Abubakar and de Vries are also part of a large international collaboration developing a free open-source diagnostic tool that could be used in place of the ADOS or ADI-R. They plan to test it in several African countries and hope it will be ready for use within five years. In the meantime, Abubakar’s collaborator, Charles Newton, is using the Kiswahili translation of the ADOS to lead Kenya’s first rigorous estimate of autism prevalence. Newton’s group has screened 11,000 children in Kilifi, aged 6 to 9. They selected the children randomly from a cohort of more than 250,000 people the researchers contact three times a year to track births, deaths and migrations in the general population. The hope is that these children represent the range of autism severity in Africa better than those in the earlier, clinic-based studies.

Their unpublished results suggest that about 1 percent of children in Kenya have the condition, in keeping with rates elsewhere. The results are preliminary, Newton says, but they make it clear that “autism is not rare in Africa.”

Raising awareness:

M

ost Africans are largely unaware of autism, despite its prevalence; to be fair, child mortality and malnutrition are more urgent concerns for most people. In surveys conducted in Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania and Ethiopia, healthcare workers and families frequently attribute its features to a curse (brought on by a taboo act such as cheating on a spouse) or to being possessed by an evil spirit.Yenus experienced this lack of awareness firsthand. In 1996, she returned to her hometown of Addis Ababa from Los Angeles, where she had worked in beauty salons for 14 years. Her 4-year-old son, Jojo, still wasn’t talking, but the doctors she saw in the U.S. told her to be patient. Shortly after she returned home, she opened Ethiopia’s first cosmetology school, the Niana School of Beauty, and noticed that Jojo seemed to regress even further. He started spinning around in circles, crying for unknown reasons and biting his finger. He did not make eye contact or pay attention to others. Yenus wondered if he might have autism, something she had heard about on American television. She read up on the condition and grew increasingly convinced that it explained Jojo’s behavior. She took the boy to numerous doctors in Addis Ababa, but no one knew what she was talking about. “There was no knowledge about autism in Ethiopia,” she says. “The word autism didn’t exist.” So she diagnosed him herself based on what she had read in books that her husband sent her from the U.S.

In 1999, she held a star-studded weeklong exhibition about traditional and modern beauty products and services. She decided to use the media attention that event attracted as an opportunity to talk about her son and his condition. “I made sure everybody understood it’s not a curse,” she says.

Jojo received an official diagnosis about a year later, when he was 8. Yenus had taken him to see a psychiatrist in Oxford, England, where they were visiting family. The diagnosis did little to improve Jojo’s situation back home. School after school expelled him because his teachers could not control him. And as Yenus continued to educate the public about autism through frequent appearances on TV and radio programs, she grew distressed by the experiences of families less fortunate than hers. She heard horrifying accounts of children rejected by their families and cut off from even the most basic care.

In April 2002, Yenus used her savings from the beauty school to rent a small house in Addis Ababa, where she opened the Joy Center for Autism. She started with just four students, including her son. As demand grew, she admitted more children and hired staff. Within a year and a half, the school had outgrown its original location and moved to its current site: a house tucked away behind stone walls, shrubbery and a tall green gate in a quiet residential neighborhood in the southwestern part of the city. As of September, the school has 80 students and 53 staff.

Yenus is a well-known figure in Ethiopia and recognized elsewhere in Africa. She appears regularly on TV and radio. “I think you can credit her with being the main person responsible for raising autism awareness,” says Rosa Hoekstra, lecturer in psychology at Kings College London. “She’s really a very powerful, inspiring figure.” But Yenus remains dissatisfied. In Ethiopia, as in other African countries, there are no laws to guarantee children with autism or other special needs the right to public education. To date, there are only two schools in Addis Ababa that specialize in autism — the Joy Center and the Nehemiah Center, founded by a group of families with children on the spectrum in 2010. Together, the two schools have more than 400 children on waiting lists.

The schools provide some therapies that are loosely derived from evidence-based approaches, such as applied behavioral analysis, but other offerings are not. At the Joy Center, for example, children receive occupational therapy, sensory integration therapy, music therapy and lessons in art, reading, writing and social skills, as well as a speech therapy called “Abugida fonetics,” which Yenus developed for her son. It involves teaching children how to speak by breaking words down into simple syllables and showing them pictures of mouths making each sound. The idea is that the children learn to mimic those movements.

Yenus credits this technique for her son’s ability to say simple phrases. But experts say it’s unclear whether these homemade treatments help. “I think I understand why people are driven to generating their own [treatments] when the system doesn’t provide it,” de Vries says. But at the same time, he says, few people try to use proven therapies or collect the types of data needed to validate their homegrown treatments.

Some African researchers, including Waganesh Zeleke, are hoping to collect those data. Zeleke worked as a staff psychologist at the Joy Center before earning her doctorate in the U.S., and she returns each year. She is trying to evaluate the treatments offered there and at the Nehemiah Center. She has found that most of the staff at these schools lack any knowledge of autism or experience providing autism treatments prior to being hired. “Most of their knowledge comes out of self-learning,” says Zeleke, now assistant professor of clinical mental health counseling at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. “It’s all informal, intuition-based.”

Both centers also lack documentation about what the treatments entail or formal assessments of children’s behaviors before and after receiving the therapies. Zeleke says she thinks the treatments are effective, but without any data it’s impossible to tell for sure. She’s working with staff at both schools to teach them how to assess and measure their methods rigorously.

”“The fact that many African people believe that autism is caused by a curse or spirits, I don’t think that’s culturally any more unusual than some people saying that autism is caused by vaccinations.” Petrus de Vries

Cultural lessons:

A

s the meeting in September made clear, researchers in Africa are primarily focused on long-term scientific goals — but recognize families’ acute need for help. “It’s pointless to do neuroscience if people don’t get access to diagnosis and treatment,” de Vries says. “It’s pointless to do a prevalence study if all it does is to say how big our problem is, and we have no solutions for the problem.”He and others have started to collaborate with local communities to make more immediate gains. Hoekstra and her Ethiopian team, for example, have partnered with the country’s Federal Ministry of Health to educate its nearly 40,000 health extension workers about mental health conditions, including autism. These workers live in rural areas and provide primary health services, but they have historically received no training in mental health or developmental conditions. Her results so far show that the training reduces stigma and misconceptions about autism among the workers.

Other projects sidestep the lack of trained autism experts and focus on helping parents directly — teaching them to provide evidence-based therapies to their children rather than relying on trips to doctors or other experts. For instance, Lauren Franz at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, is adapting a therapy called the Early Start Denver Model for use in South Africa. The therapy uses play routines to help children with autism learn skills such as speaking and socializing. Hoekstra and her colleagues are adapting a parent-training program developed by the World Health Organization. Because literacy in Ethiopia is low, the team has cut much of the text in the training materials for parents and relies primarily on picture-based instructions. “What we are trying to do is to go from a close-to-nonexistent services situation to a situation where we can actually start offering families some handles or supports,” Hoekstra says.

These researchers are incorporating what they are learning about African views and experiences. One major lesson is the importance of working with local beliefs — and that’s true anywhere in the world. “The fact that many African people believe that autism is caused by a curse or spirits, I don’t think that’s culturally any more unusual than some people saying that autism is caused by vaccinations or by particular diets, or by particular heavy metals,” de Vries says. “They’re all cultural beliefs, in a way.”

Yenus says the programs seem to work best when experts solicit the opinions of parents like her — and wishes they would do so more often. “There should be no research about us without us,” she says. “Even though we are not psychiatrists, we are not doctors, we are doing the work. We have the knowledge as well.”

Yenus is using that knowledge to expand her center’s reach. She has begun training teachers in 10 mainstream schools in and around Addis Ababa to help them provide inclusive education for children with autism. And last year, the Ethiopian government gave her a rent-free plot of land to build another school for children with autism, on the outskirts of Addis Ababa. The new school, which Yenus calls her “Joy Center of Excellence,” is set to accommodate roughly 400 registered students. She is still raising money and recruiting staff but helped to lay the building’s cornerstone in March. She says the facility will be equipped with dedicated treatment rooms, as well as long-term living quarters for children in the direst need of help.

Fekerte, now 18, continues to attend the Joy Center for Autism every week. She still does not speak but has figured out other ways to communicate. One afternoon in September, as her mother talked with a visitor, she retrieved a glass from a cupboard and gave it to her mother to signal her thirst. Demas works part-time at the center, along with five other single mothers of children with autism, preparing dried spice blends sold to area hospitals, businesses and individuals. The job provides the women with a small salary and the flexibility to check in on their children during the day. Before she met Yenus, Demas says, she contemplated killing her daughter and herself. “This is a second chance at life,” she says, speaking through an interpreter. “Now I’m a different person.”

For Yenus, there is no greater motivation.

“It’s a big responsibility I have, that is on my shoulders,” Yenus says. “That’s why I keep doing this, because when all those people look at you, hoping that something will be done because of your activities, because of your shouting and talking to whoever, you don’t want to just leave them alone. Even give them a little hope — it means a lot to me.”

Syndication

This article was republished in The Independent.

Recommended reading

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

FDA website no longer warns against bogus autism therapies, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

PIEZO channels are opening the study of mechanosensation in unexpected places

Michael Shadlen explains how theory of mind ushers nonconscious thoughts into consciousness