Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Certain gene variants may have greater weight in determining autism likelihood for some populations, a new study shows.

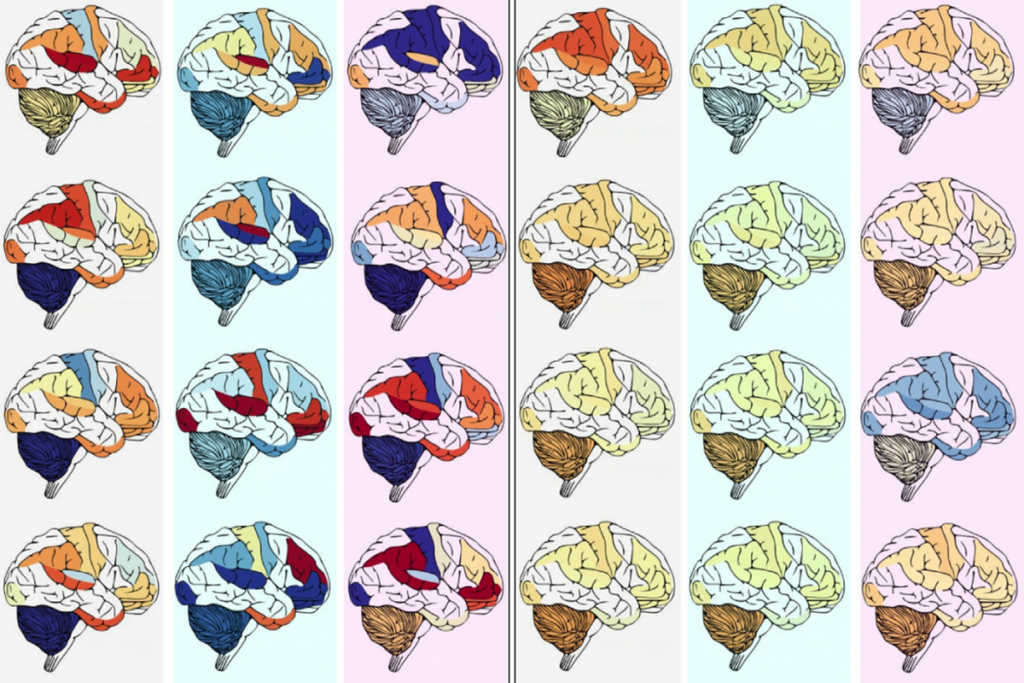

The balance of common and rare genetic variation linked to autism is different in people of African descent than in those of European descent, according to the first analysis of a large cohort of autistic African Americans and their families. Polygenic scores for autism that are derived largely from people of European ancestry have limited applicability for African Americans, and distinct rare variants may contribute to autism in this population, the study shows.

The findings appear in a preprint posted on medRxiv in November.

The work underscores that including people of different ancestries in autism research is important for both research and public health, says principal investigator Daniel Geschwind, professor of human genetics, neurology and psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“If we don’t have representative populations in our studies, then we’re not going to understand genetic risk across all of our populations in an equitable way,” he says.

That diversity has largely been untapped in autism genetics research, Geschwind says, which motivated him and his colleagues to create the Genetics of Neurodevelopment in African Americans (GENAA) Consortium in 2008 to add more people of African descent to autism genetics studies. So far, the consortium has recruited 1,912 autistic people who identify as Black or African American and their family members in the Bronx, Atlanta, St. Louis and Los Angeles.

The new study “is an important effort to level the playing field in the genetics of autism across diverse ancestral groups,” wrote Daniel Weinberger in an email to The Transmitter. Weinberger directs the Lieber Institute for Brain Development at Johns Hopkins University and was not involved in the work.

The paper adds details to the understanding of autism genetics, including how frequently different types of variants occur in autism-linked genes in African Americans, says Maria Chahrour, associate professor of neuroscience at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the work.

“We need to know all this information,” she says.

G

Autistic people of European ancestry inherited polygenic risk at higher rates than their non-autistic siblings. But the same was not true for African-American autistic people, the team found, indicating that the tool is not fully transferable to people of varied ancestries.

This is the first time researchers have compared autism polygenic scores in people with different ancestries, an important step, Chahrour says.

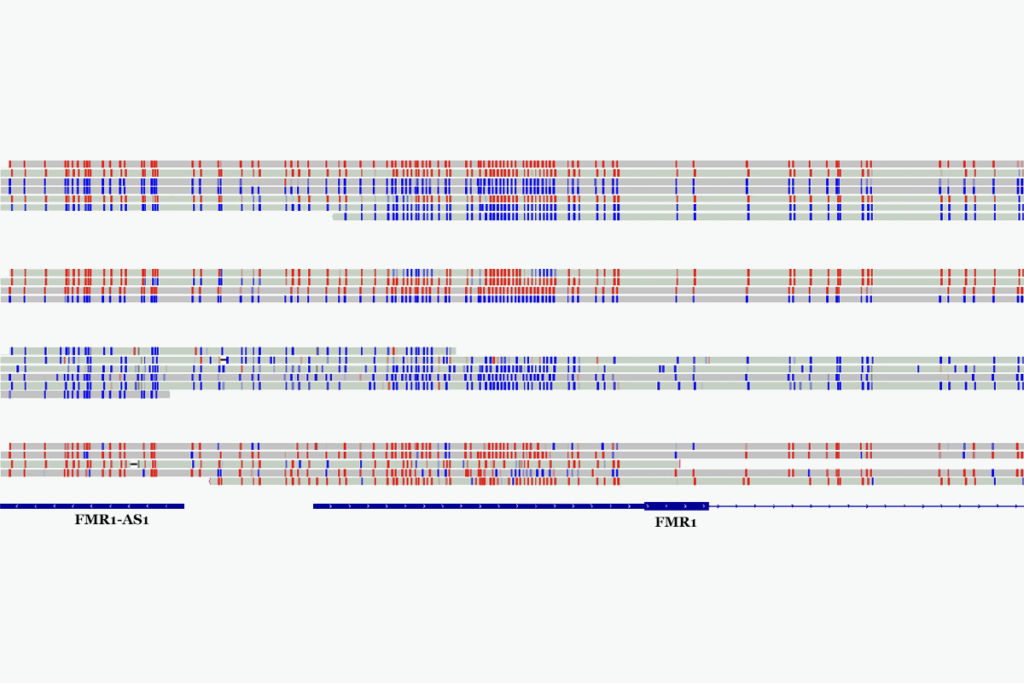

In an analysis of whole-exome data, some rare variants were strongly linked to autism regardless of ancestry. Autistic people of African descent in GENAA, though, didn’t show the preponderance of spontaneous de-novo mutations observed in people of European ancestry. Instead, they have more inherited variants that are currently classified as rare, the study found.

That can be explained by the vast genetic diversity in Africa, Geschwind says: If there’s more variation in the genome as a whole, more variation will be passed down.

Some of the identified variants occur in genes that have not been previously linked to autism, the researchers found. Those genes’ links to autism did not meet a stringent threshold for statistical significance, but that’s likely because of small sample size and could change with larger cohorts, Geschwind says. “We’re just at the limit of our power to begin to identify those things.”

S

“You can see if these alleles show up and at what frequency do they show up in a purely African background, since they do that for a purely European,” she says. “That’s a very big missing analysis.”

It would also be helpful to know the specific countries in Africa from which people in the GENAA cohort are descended, Chahrour says. The researchers should also examine whether genetic results for African-American people in SPARK, a large genetic study of autistic people in the United States, change with the addition of the new GENAA dataset. (SPARK is funded by the Simons Foundation, The Transmitter’s parent organization.)

Comparisons with other datasets would be interesting, as would looking into ancestral origin in greater detail, Geschwind says. The current study is “primarily a discovery analysis,” he says.

He says he expects that adding GENAA data would help SPARK clinicians identify likely genetic causes of autism in more African Americans. He and his team are working to sequence the whole genomes of an expanded GENAA cohort.

The consortium hopes to double its sample size in the next few years, Geschwind says.

Recommended reading

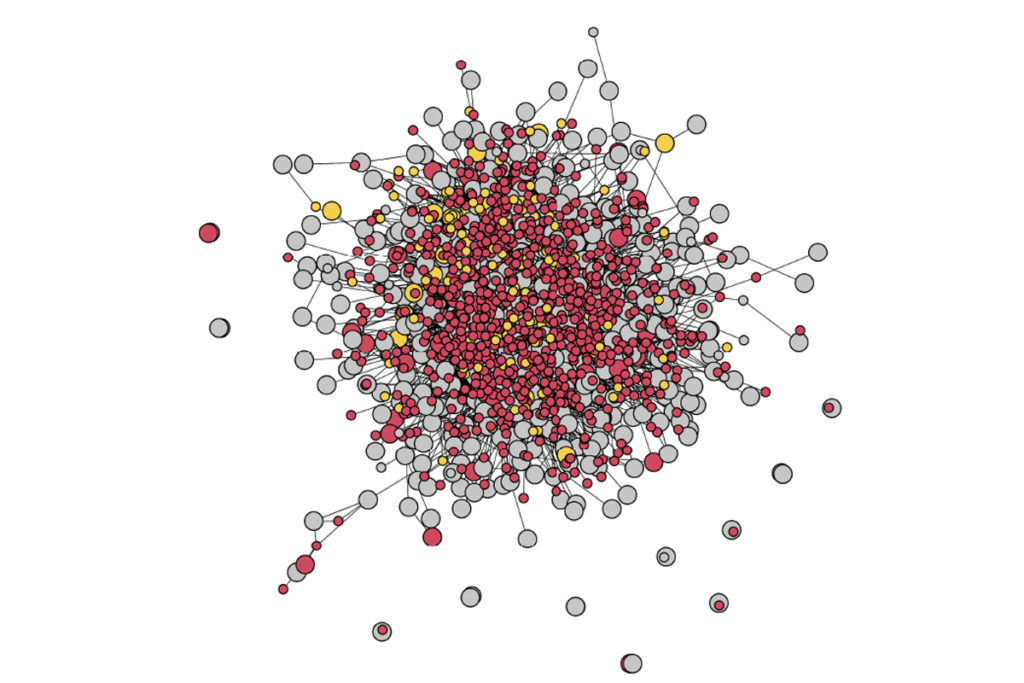

Sequencing study spotlights tight web of genes tied to autism

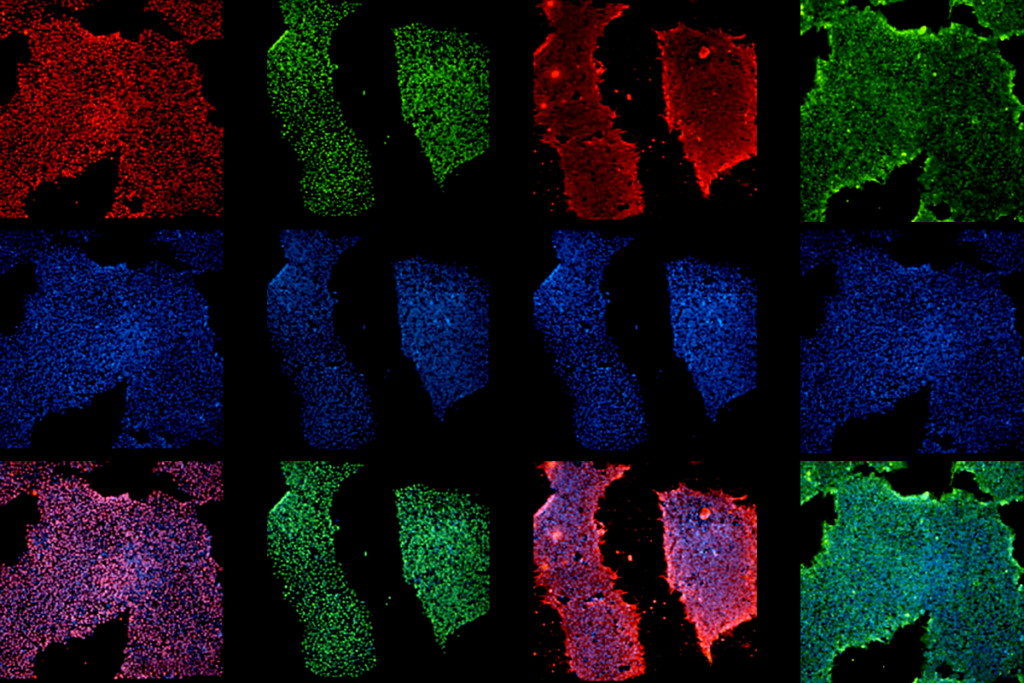

Bringing African ancestry into cellular neuroscience

X marks the spot in search for autism variants

Explore more from The Transmitter

Genetic profiles separate early, late autism diagnoses

Long-read sequencing unearths overlooked autism-linked variants