On 22 September, Richard Frye was in Saudi Arabia when he says he woke up to an email from Mehmet Oz, head of the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, inviting him to the White House that afternoon.

Although Frye was unable to attend, he soon learned that Oz’s boss, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., was making an announcement that day about leucovorin, a folinic acid supplement that Frye has studied and prescribed for the treatment of autism for nearly 20 years.

Frye is a child neurologist and researcher at the Rossignol Medical Center, a functional medicine clinic in Phoenix, Arizona. He led one of the five published small, placebo-controlled studies of leucovorin in autistic people. He also recently completed a multicenter trial funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), whose results have not yet been published.

In addition to his clinical work, Frye is the author of the self-published book “The Folate Fix” and a consultant for Neuroneeds, a Connecticut-based company that markets a high-folate supplement called Spectrum Needs.

That afternoon at the White House, Kennedy described leucovorin as “an exciting therapy that may benefit large numbers of children who suffer from autism.” The public rollout, however, differs from the steps the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has actually taken, which is to approve the expansion of GSK’s leucovorin label to include its use in treating cerebral folate deficiency, a rare disorder that can resemble autism.

“The problem is that this is going to be touted as a cure for autism,” says David Amaral, director of the University of California, Davis MIND Institute. “It clearly hasn’t been demonstrated in a standard clinical trial.”

Frye’s own research record traces the gulf between promise and proof. His first leucovorin trial was suspended by regulators for reasons including “lack of PI oversight,” according to documents Frye shared with The Transmitter. The NIH-funded trial has been mired in delays amid his 2022 departure from Phoenix Children’s Hospital. Even Frye himself is ambivalent about the federal government’s decision to hype the drug for autism without further study. “For the administration to come through and say there is a treatment for autism is a major turning point,” he says. “Could they have given some more nuance to it? Sure.”

O

ver his nearly three decades as a doctor, Frye has built a reputation in the autism research community for testing unconventional treatments, ranging from nutritional supplements to hyperbaric therapy.“He seems to cover a remarkably wide range of things that cause autism or cure autism,” says Dorothy Bishop, emeritus professor of developmental neuropsychology at the University of Oxford. “The evidence never looks very strong to me.”

Frye says some colleagues have called him a “quack,” and one accused him—falsely, he adds—of giving a patient hypervitaminosis. He considers himself an evidence-based physician, but he rejects elements of the genetic consensus on autism and says he chases only alternative therapies he finds biologically plausible.

His interest in leucovorin is tied to the unproven theory that mitochondrial disorders underlie autism in many cases and that vaccines may aggravate them by producing oxidative stress during an immune reaction.

“Several times a year when I used to do the hospital thing, I’d have a child come in that was injured by a vaccine,” Frye says.

In 2006, he co-authored a case report in the Journal of Child Neurology about a 6-year-old girl he saw during his fellowship at Boston Children’s Hospital who had been diagnosed with autism and mitochondrial dysfunction following a series of five vaccines.

It later emerged that the subject of the article was the daughter of the first author, Jon Poling, then a neurology resident at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Poling had also filed a claim under the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, a division of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which would ultimately award an estimated $20 million in lifetime compensation.

The journal’s editor at the time, Roger Brumback, subsequently called the researchers’ failure to disclose that conflict of interest “an appallingly troubling issue.” Frye and his co-authors published formal apologies, but the study—and the court’s one-off ruling—would be widely embraced by vaccine skeptics as evidence for a mechanism by which vaccines could lead to autism.

Several of Frye’s patients came to him after filing claims for compensation from the government in the vaccine court, and Frye himself has offered expert testimony that vaccines “can induce or exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction in individuals with mitochondrial disorders by increasing oxidative stress,” as one judge concluded in a 2014 ruling.

Government experts disputed aspects of Frye’s theory and diagnoses.

Gerald Raymond, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins University, told the court that Frye’s theory was “not sound” and argued that it required “some degree of obfuscation.” In fact, the body’s response to a respiratory infection, he testified, would be a “more suitable trigger” than a vaccine.

After the parents of one autistic boy—referred to as L.V. in the court’s decision—filed a claim in July 2008, they sought treatment from Frye, who diagnosed the boy with a “definite” mitochondrial disease, according to court records. Frye said L.V. scored 9 out of 12 points on the often-used Morava criteria, even though most laboratory tests had come back negative.

Bruce Cohen, a neurologist and director of the Mitochondrial Center at Akron Children’s Hospital, reviewed L.V.’s records for the court and gave him a zero, and noted that the Morava criteria were losing favor relative to genetic testing.

Two years later, Frye diagnosed another claimant, A.P.M., with cerebral folate deficiency, citing folate receptor antibodies “in the high range” in his blood, even though his cerebrospinal fluid folate levels were still at the low end of the normal range, according to court records.

Although Frye has advocated for removing aluminum-based adjuvants from vaccines in the past, he says he believes that vaccine injuries are relatively rare.

“If we spend the next 20 years just concentrating on vaccines, we are going to get nowhere,” he says.

F

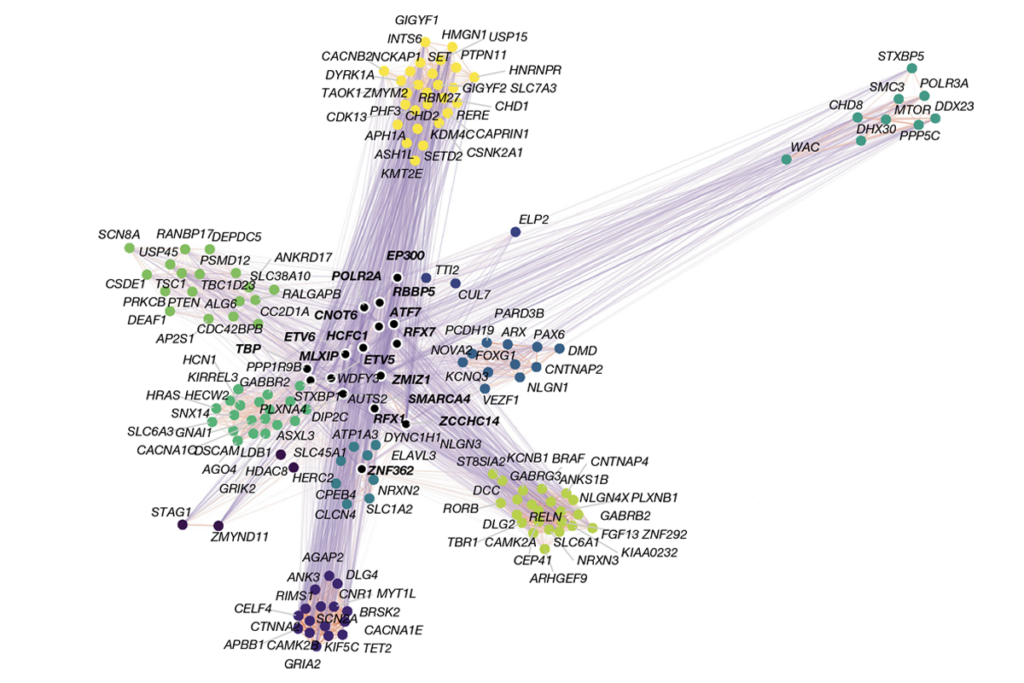

rye, instead, has focused his career on possible treatments.In 2012, he was the lead author of an influential paper in Molecular Psychiatry that reported that 70 of 93 autistic people he and his co-authors tested in his clinic had antibodies that prevented folate from crossing the blood-brain barrier to varying degrees, which could impair mitochondrial function.

The study was not a randomized trial, but the fact that one-third of those participants appeared to show improvements in language, attention and stereotypical behaviors after taking oral leucovorin encouraged other doctors to consider the drug.

David Beversdorf, a neurologist at the University of Missouri, says that he has prescribed leucovorin to patients who test positive for antibodies, in accordance with Frye’s protocol, and found that some do show a slight benefit. “There are a lot of medications like that,” he says. “It’s not a panacea. Not a cure. Not remotely.”

Other researchers agree that some people with autism seem to have a mild form of folate deficiency that has not been fully characterized. Chronic folate deficiency is diagnosed with a spinal tap, an invasive procedure, but Frye says a blood antibody test is sufficient to prescribe leucovorin.

“I’m not convinced we can do a simple blood test to determine that,” says Lawrence Scahill, a pediatrician at Emory University’s Marcus Autism Center.

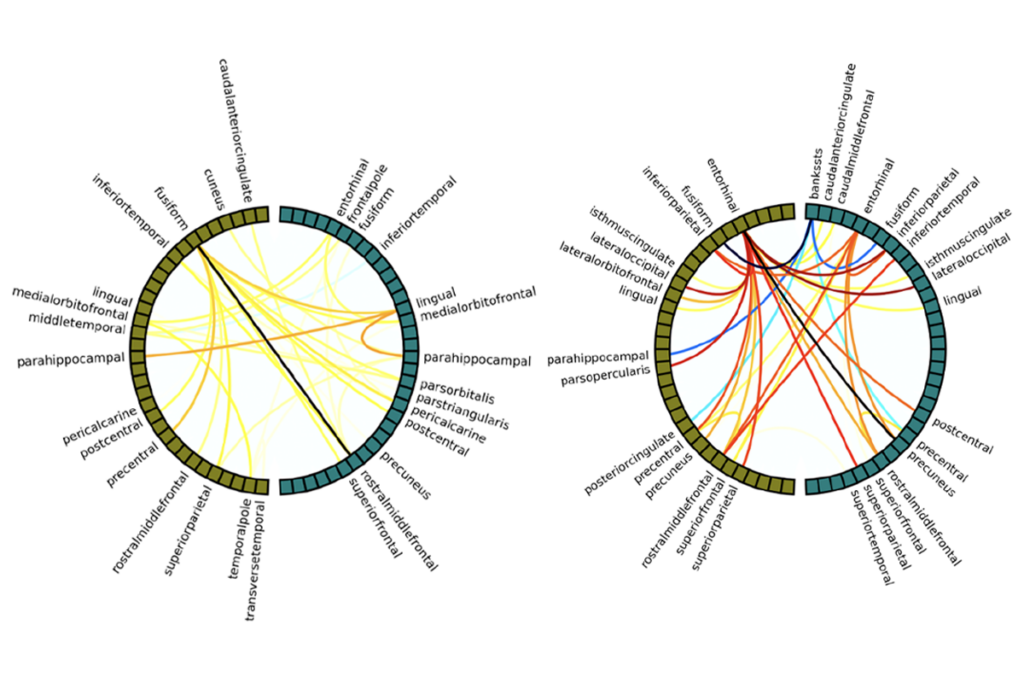

In 2018, Frye’s view continued to gain traction after he reported positive results from a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of leucovorin in 48 children ranging from 3 to 13 years old at the Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock. The study reported a 7-point improvement—a large effect—in verbal language skills measured with standardized assessments.

But Scahill says it is difficult to draw conclusions because, with such a wide age range of participants, Frye combined scores from three different age-specific assessment instruments.

The study, which was originally slated to include additional trial sites in Arkansas, New York and Texas, had more fundamental problems, according to emails and other records that Frye shared with The Transmitter.

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, which oversaw the study, found it “very difficult to monitor because of the numerous changes to the protocol and consent,” according to an email to Frye from the university’s Office of Research Regulatory Affairs.

In June 2015, the FDA placed the study on hold for compliance violations that posed “unreasonable and significant risk of illness or injury to human subjects,” and the university terminated the trial five months later.

Frye says the university’s monitors were biased against him. “They didn’t like our study,” he says.

The university’s vice chancellor for communications and marketing, Leslie Taylor, says she cannot comment on “specific personnel issues” but noted that the university’s “research oversight process is governed by well-established procedures designed to protect study participants and ensure scientific integrity.”

Two years later, Frye took a position at Phoenix Children’s Hospital and soon launched a new multicenter trial with the support of the NIH.

At Frye’s request, Scahill agreed to serve as the trial’s sponsor with the FDA, and he tried to revise Frye’s protocol, including the verbal language assessment.

But one problem after another set the study back.

The trial was getting off the ground during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Frye insisted on using a compounding pharmacy because he didn’t trust the generic pills that contained dyes and additives, Scahill says.

After starting the trial, however, they had to shift to a liquid version of the drug because the raw ingredients for the pills were no longer available.

Next, Scahill resigned as the sponsor when Frye refused to accept his take on the language assessment. “I respect Dr. Scahill for his important work, but we just didn’t see eye to eye on this one,” Frye says.

Finally, in 2022, Phoenix Children’s Hospital fired Frye without warning. It cut off his email and advised his collaborators “that they should not share data with him,” according to an ongoing lawsuit he filed last year against the hospital in the Arizona Superior Court.

Frye says he was terminated without cause. The hospital has not disclosed the reason and did not respond to a request for comment.

“It was a mess,” says Harris Huberman, a pediatrician at Downstate Health Sciences University, who is collaborating on that study. “We’ve since moved ahead.”

The NIH declined to move Frye’s grant to his new institution, the Rossignol Medical Center, which is run by his longtime collaborator, Dan Rossignol.

The Rossignol clinic, which has offices in Arizona, California and Florida, emphasizes a gluten-free diet and antioxidant supplements in the treatment of autism.

Frye says he has since obtained his data and will be sharing the results in the future.

The largest double-blind clinical trial on leucovorin to date, published last year by India-based researchers in the European Journal of Pediatrics, reported modest improvements in scores on the Childhood Autism Rating Scale among 40 participants with folate receptor antibodies who received leucovorin.

Several commenters on PubPeer, including Thomas Challman and Scott Myers of the Giesinger College of Health Sciences, have pointed out “significant errors” in results tables and other “statistical inconsistencies” that call into question the trial’s major findings.

The corresponding author, Indar Sharawat of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, did not respond to a request for comment, but his response on PubPeer states that their conclusions hold following a reanalysis.

As for Frye, he says his organization, the Autism Discovery & Treatment Foundation, has pitched Kennedy’s team on supporting the testing of his additive-free formulation, but the group was not chosen as part of the NIH’s $50 million autism research initiative. His work was also not on the list of 23 studies, shared with The Transmitter, that the FDA took into account in its leucovorin decision.

“It is rich that the NIH and Big Pharma want to take over leucovorin when they and the universities have fought my research for 20 years,” Frye says.