Long-term project charts methylation patterns in pregnancy

By studying pregnant women who already have a child with autism, researchers hope to understand how epigenetic changes — those that affect gene expression but don’t directly alter DNA — during pregnancy influences risk of the disorder.

By studying pregnant women who already have a child with autism, researchers hope to understand how epigenetic changes — those that affect gene expression but don’t directly alter DNA — during pregnancy influence risk of the disorder.

One group is using a method called CHARM, or comprehensive high-throughput arrays for relative methylation, to assess methylation, the addition of a methyl group to DNA that typically turns off gene expression. The researchers are studying how methylation changes during pregnancy and in young children over time, as well as in response to specific environmental exposures.

A second group is measuring ‘methylation capacity,’ an indirect measure of how well a cell can methylate genes, in pregnant women to determine whether abnormal levels can predict a later autism diagnosis for the child.

Both projects, presented yesterday at the International Meeting for Autism Research in Toronto, are part of the Early Autism Risk Longitudinal Investigation (EARLI), which aims to sort out the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to autism.

EARLI results:

Launched in 2009, EARLI is focused on pregnant women who already have a child with autism and have a higher-than-normal risk of having another. About 10 to 25 percent of siblings of a child with autism will go on to develop the disorder, compared with an average risk of about 1 percent. (One of EARLI’s goals is to get a better handle on that number.)

Researchers at a number of sites across the U.S. are collecting blood and other biological samples from these women and their children as well as data on their diet, medication use, medical conditions, pesticide exposure, vaccine use, occupational history and additional factors. The children get behavioral assessments beginning at 6 months of age and through 36 months, when they can be tested for autism. EARLI ultimately aims to enroll 1,200 mothers.

Because the study is prospective, meaning that data are collected over time, the researchers say they hope it will help clarify how genetic and environmental factors interact to raise autism risk. Epigenetics, which can be influenced by the environment, is one way to examine this interaction. (Retrospective studies rely on participants to recall information about the past and so are more subject to bias.)

One of the two EARLI projects presented yesterday aims to link methylation data from women during and after pregnancy with environmental exposure. Preliminary findings show that methylation appears to be stable throughout pregnancy.

The second looked at metabolic biomarkers in pregnant women. The researchers had previously found that women who have children with autism have an abnormal methylation capacity, defined as the ratio of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) SAM is a critical ingredient of methylation. The methylation process, in turn, produces SAH.

EARLI gave the team the opportunity to determine whether this pattern is present in pregnancy and, if so, whether it predicts the child’s risk of autism.

The researchers found that about 15 percent of the 60 women have low methylation capacity compared with 100 controls. However, they won’t know for about three years, when the children can reliably be diagnosed with autism, whether this is predictive of the disorder.

Still, the 15 percent figure is interesting because it aligns with the risk for siblings of children with autism, notes lead investigator Jill James, director of the Metabolic Genomics Laboratory at Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

For more reports from the 2012 International Meeting for Autism Research, please click here.

Recommended reading

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Profiles of neurodevelopmental conditions; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

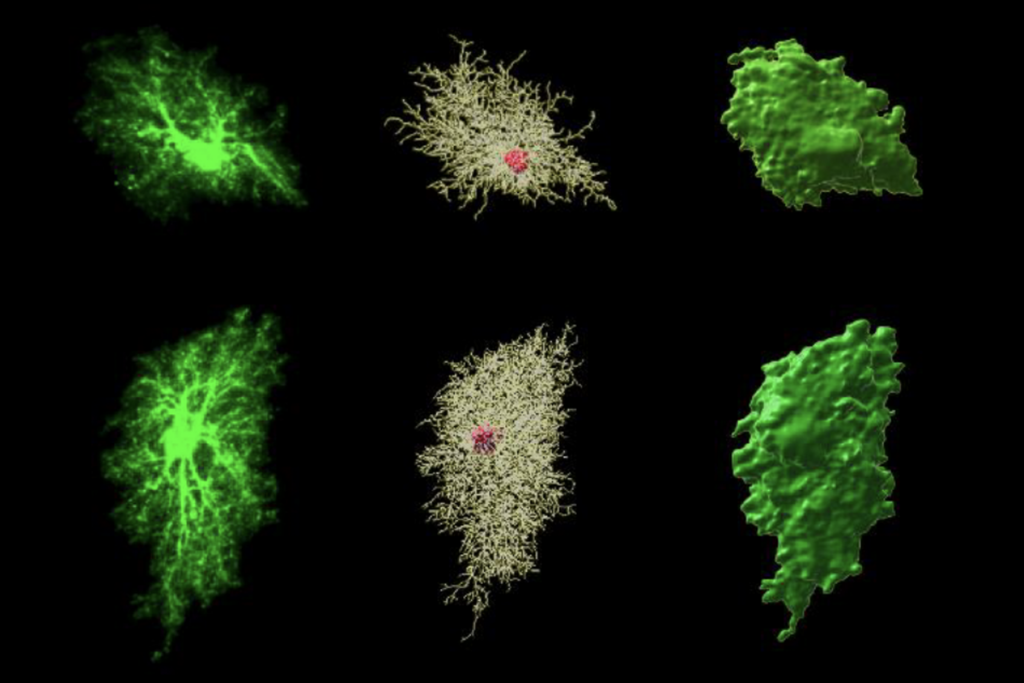

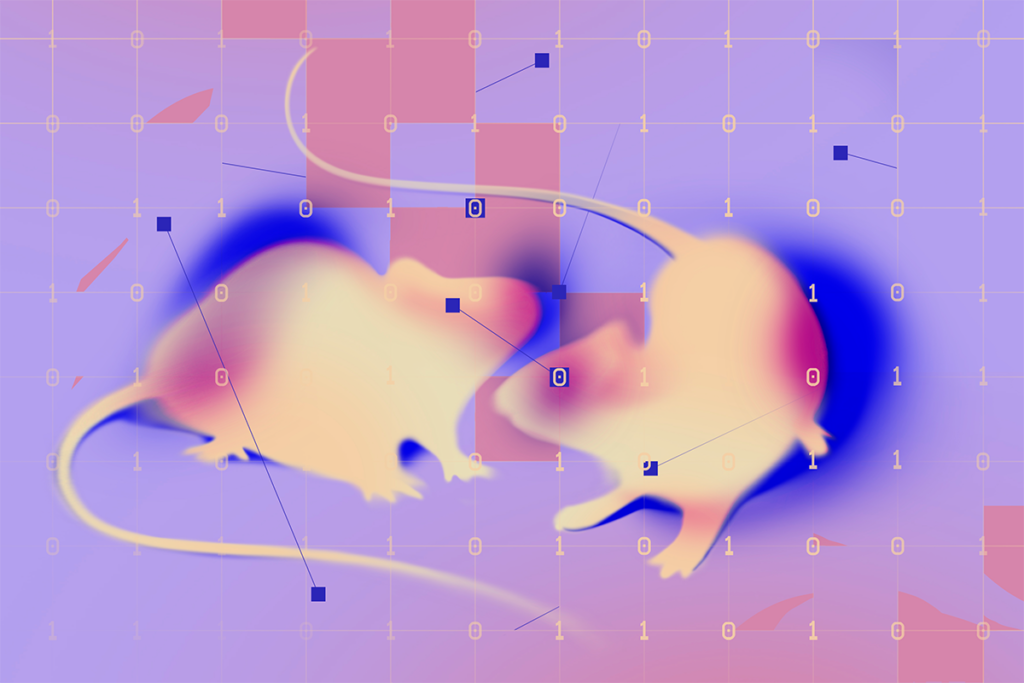

How artificial agents can help us understand social recognition

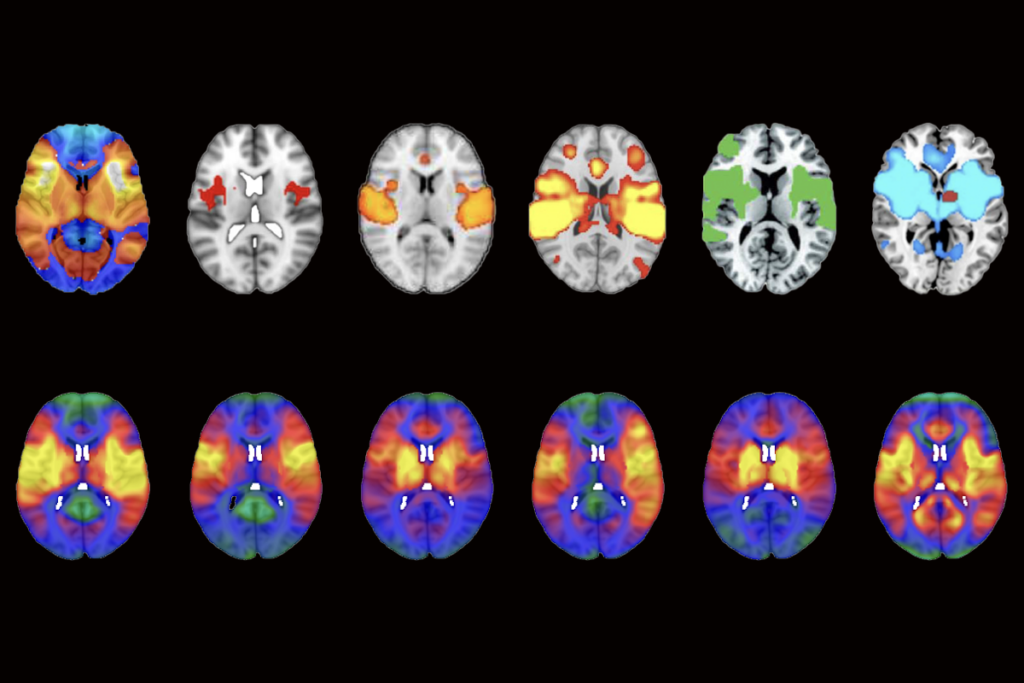

Methodological flaw may upend network mapping tool