For teens with autism, behavioral issues boost risk of police run-ins

Young people with autism who have psychiatric problems may stand a ninefold greater chance of having an encounter with the police than do others on the spectrum.

Young people with autism who have serious psychiatric problems stand a ninefold greater chance of having an encounter with the police than do others on the spectrum, according to a new study1.

Having behavioral problems that lead to disciplinary action in school also ups the chances of an encounter with police.

“These are pretty common events that are affecting kids with autism,” says David Mandell, professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, who co-led the study. “We need to be concerned about the [problems] and how to stop them,” he says.

The study is among the first to look at the links between behavioral problems, hospital visits for psychiatric problems and police emergencies among people with autism.

It’s important to study these interactions rather than looking at each factor in isolation, says Yona Lunsky, professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto in Canada, who was not involved in the study. “Is there one underlying thing that’s leading to all of this? Or are they all separate things?” Either way, she says, “it’s important for us to think holistically.”

Shared experiences:

Mandell and his colleagues analyzed 2,525 responses to a survey called the Pennsylvania Autism Needs Assessment, which asks questions about service use and problems that people with autism often face. The researchers included answers from parents or caregivers of young people with autism who were 6 to 21 years old.

One survey question asks whether a child has been given a detention or been suspended or expelled from school in the past year. The survey also covers psychiatric treatment — asking parents, for instance, whether a child has been hospitalized or visited an emergency room for a psychiatric issue. It also addresses encounters with the criminal justice system, such as the police being called because of the child’s actions, or time spent in a juvenile detention center.

The team found that 378 children, or 15 percent, have had disciplinary problems at school. Nearly 200, or 8 percent, have had contact with police, and about 8 percent have received psychiatric treatment in a hospital. The results appeared 21 November in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Not surprisingly, teenagers have more contact with the police than do younger children. About 14 percent of children aged 13 to 17 have encountered the police, compared with 4 percent of children aged 6 to 12. In a study published last February, researchers reported that 14 percent of people with autism have been stopped and questioned by police at least once by age 192.

The results suggest that intervening in early adolescence could lower the chances of an individual on the spectrum interacting with the criminal justice system.

“This is mostly happening during their early teenage years while they’re still in school, and this is where we should most likely target interventions and support systems,” says Julianna Rava, a lead investigator in the February study and a health science policy analyst for the National Institute of Mental Health’s Office of Autism Research Coordination.

Red flag:

Children whose parents or caregivers earn between $40,000 and $79,000 a year are twice as likely to have had police contact as children from higher-income families. The researchers didn’t find a relationship between race and disciplinary issues and police contact.

The survey responses did not include information about when the children had behavioral problems relative to psychiatric issues or police contact. But disruptive behavior at school may often be the initial event, and could land a child in the hospital or in police custody.

“This is not a failure of the kid; it’s a failure of the system to provide appropriate supports,” Mandell says. “We would put a lot of money on the idea that school disciplinary action is first, and so we ought to be thinking about that as a big red flag.”

The researchers did not look at children with autism who have behavioral problems that do not result in punishment at school — a shortcoming of the study, notes Matthew Siegel, director of the Developmental Disorders Program at Spring Harbor Hospital in Maine, who was not involved in the work. Most children who visit the psychiatric units where Siegel works are never suspended or expelled from school, he says.

“Those discipline things aren’t applied to them because they have autism,” he says. Researchers should measure psychiatric hospitalization and police contact alongside behavioral problems that don’t necessary lead to school discipline, he says.

Mandell’s team aims to gather details about the interactions that young people with autism have with the police. They plan to analyze results from a second version of the survey that allows participants to submit online links to their police and court records.

References:

Recommended reading

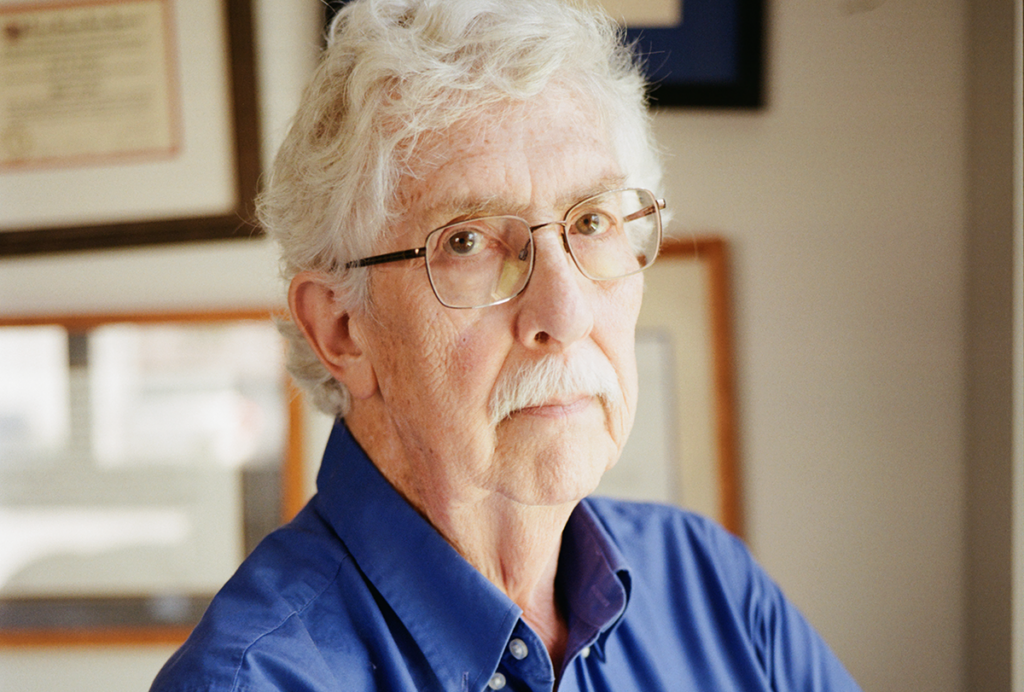

How pragmatism and passion drive Fred Volkmar—even after retirement

Explore more from The Transmitter

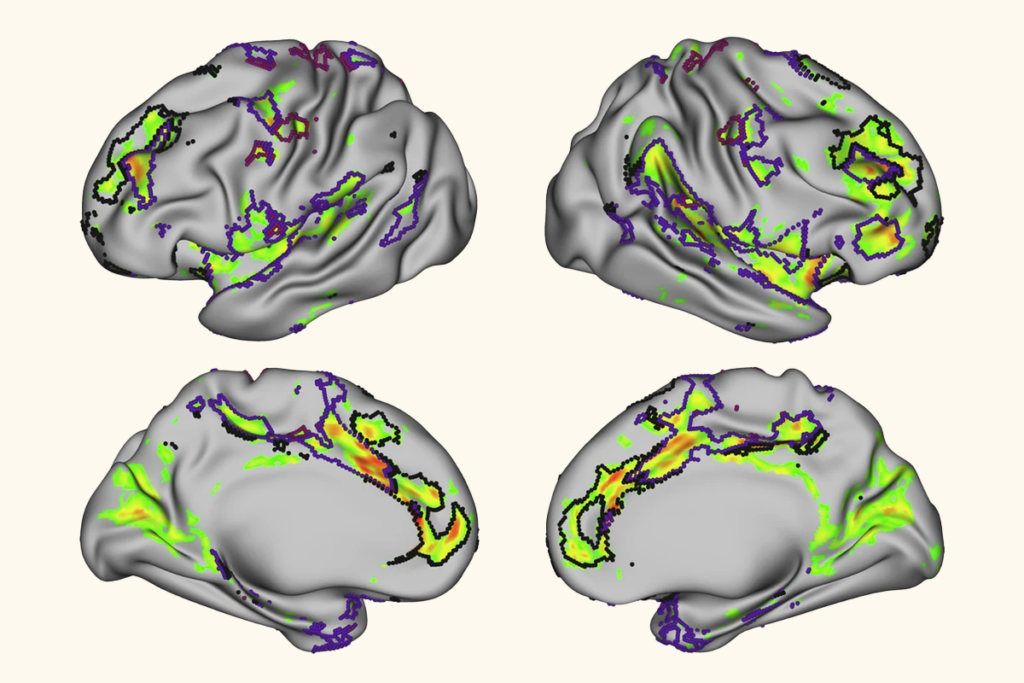

‘Ancient’ brainstem structure evolved beyond basic motor control

NIDA shutters diversity fellowship program, axes active awards