The link between epilepsy and autism, explained

Autism and epileptic seizures often go hand in hand. What explains the overlap, and what does it reveal about autism’s origins?

Autism frequently co-occurs with any of a long list of other conditions. But none may be more closely linked than epilepsy. Nearly half of all autistic people have epilepsy, according to some reports, suggesting that the two conditions share underlying biology. For example, both conditions are characterized by overly excitable brains.

It’s not yet clear whether epilepsy contributes to autism or is a consequence of the condition, however.

What is the evidence that autism and epilepsy often co-occur?

One large study published in 2013 looked at nearly 6,000 autistic children and found that 12.5 percent have epilepsy1. The proportion rose to 26 percent among children older than 13 years. A 2019 study of nearly 7,000 autistic children also found that about 10 percent have epilepsy2. The number from other studies is highly variable, ranging from 2 percent up to 46 percent3.

However, these estimates all exceed epilepsy’s prevalence in the general population: 1.2 percent in the United States.

People with epilepsy are also more likely than others to have autism: A Swedish study of more than 85,000 people with epilepsy found that autism is 10 times more common in those individuals than in the general population.

Is autism associated with a certain type of epilepsy?

Apparently not. Autistic people have been known to have most types of seizures, including generalized seizures, those that originate in a specific part of the brain, and severe spasms in infancy. Some studies have suggested that certain seizure types tend to be common among autistic individuals, but the findings may be skewed because the researchers recruited participants with only some forms of autism.

Epilepsy onset appears to occur at two peaks in autistic children: early childhood and adolescence. But as many as 20 percent of autistic people with epilepsy have their first seizure in adulthood4.

Are certain forms of autism more closely associated with epilepsy than others?

Perhaps. Several studies suggest that children who have both autism and intellectual disability are more likely to have epilepsy than other autistic children1.

Autistic women are more likely to have epilepsy than are autistic men, according to some studies3; roughly three boys are diagnosed with autism for every girl, but the ratio is less than 2-to-1 among those who have both epilepsy and autism.

Motor problems, language difficulties and regression are all associated with epilepsy in an autistic person2.

Do autism and epilepsy share genetic risk factors?

Yes. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that autism and epilepsy stem from a common genetic origin. A 2013 study found significant overlap between genes linked to epilepsy and those tied to autism5. And a 2016 study found that children who have an autistic older sibling are 70 percent more likely to have epilepsy than controls, even if they do not themselves have autism6.

Researchers have linked mutations in several genes, including SCN2A and HNRNPU to epilepsy, autism or both. Certain genetic conditions related to autism, such as tuberous sclerosis or Phelan-McDermid syndrome, are also associated with epilepsy.

What might explain this overlap between autism and epilepsy?

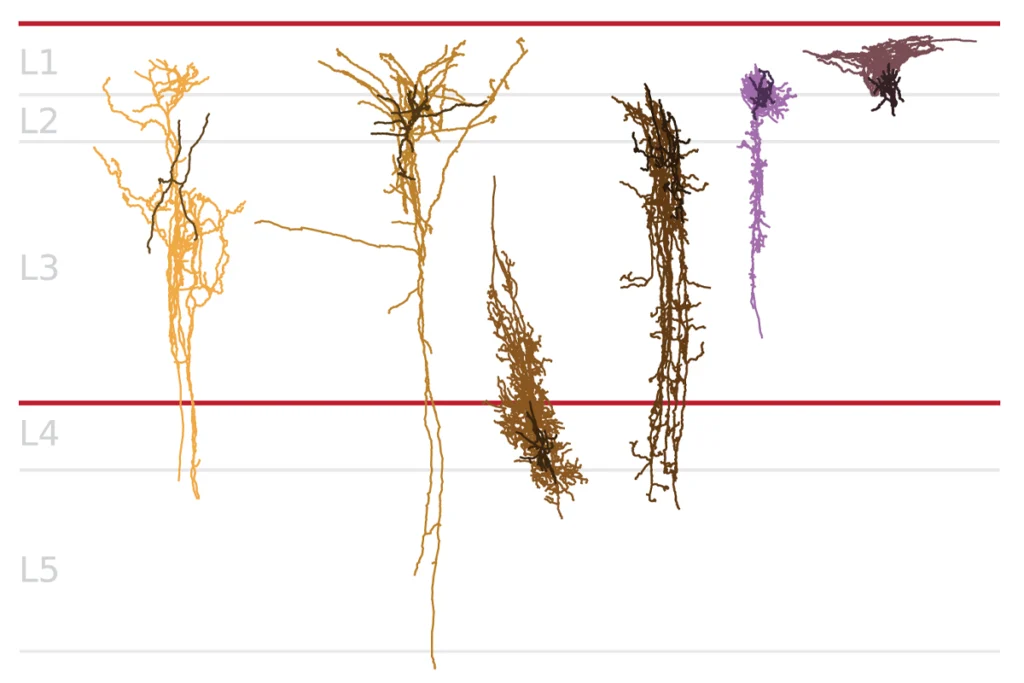

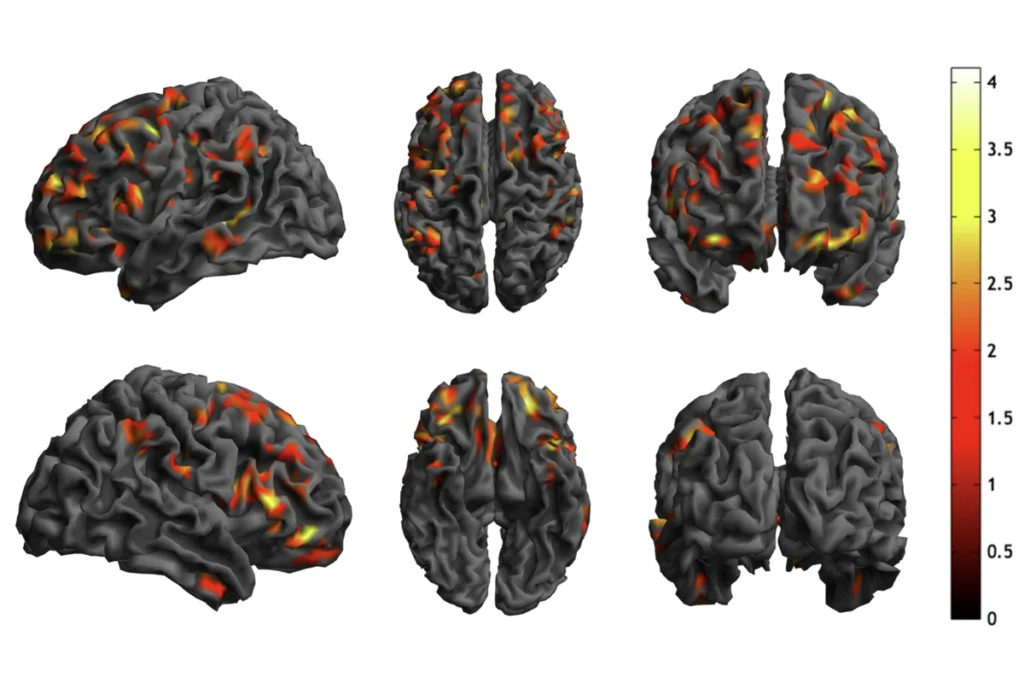

One theory for the overlap is that the conditions share common biological mechanisms. Epilepsy is characterized by too much excitation in the brain, which may stem from too little inhibition.

A landmark study published in 2003 proposed that autism may also stem from an imbalance between excitation and inhibition in the brain. There are data to support this theory from studies in both animals and people, but many experts remain skeptical.

Can epilepsy contribute to autism traits?

There is some evidence to support this theory. Having severe epileptic seizures in infancy — in particular, a harmful type called infantile spasms — has been shown to have lasting consequences for the brain. And surgery to treat severe forms of epilepsy seems to lead to long-term improvements in social behavior and cognition7,8.

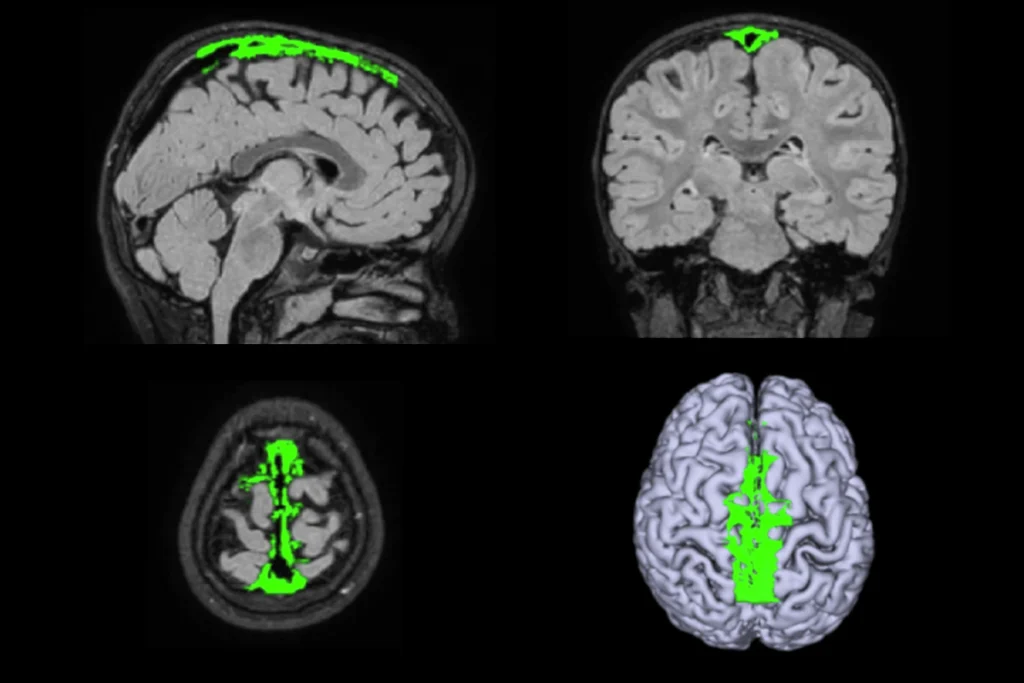

To explore the link between seizures and autism, researchers are tracking the health of newborns who have tuberous sclerosis, a genetic condition that leads to both epileptic seizures and autism. The team has so far found that the children who have seizures in the first year of life are most likely to have developmental delay. The researchers aim to test these children for autism once they turn 3.

The same team has also designed a clinical trial to see whether preventing seizures during infancy in children with tuberous sclerosis improves their overall development and prevents a later diagnosis of autism.

References:

- Viscidi E.W. et al. PLoS One 8, e67797 (2013) PubMed

- Ewen J.B. et al. Autism Res. Epub ahead of print (2019) PubMed

- El Achkar C.M. and S.J. Spence Epilepsy Behav. 47, 183-190 (2015) PubMed

- Bolton P.F. et al. Br. J. Psychiatry 198, 289-294 (2011) PubMed

- Novarino G. et al. Neuron 80, 9-11 (2013) PubMed

- Christensen J. et al. Epilepsia 57, 2011-2018 (2016) PubMed

- Kang J.W. et al. Pediatrics 142, e20180449 (2018) PubMed

- Skirrow C. et al. Epilepsia 60, 872-884 (2019) PubMed

Recommended reading

Okur-Chung neurodevelopmental syndrome; excess CSF; autistic girls

New catalog charts familial ties from autism to 90 other conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

Karen Adolph explains how we develop our ability to move through the world

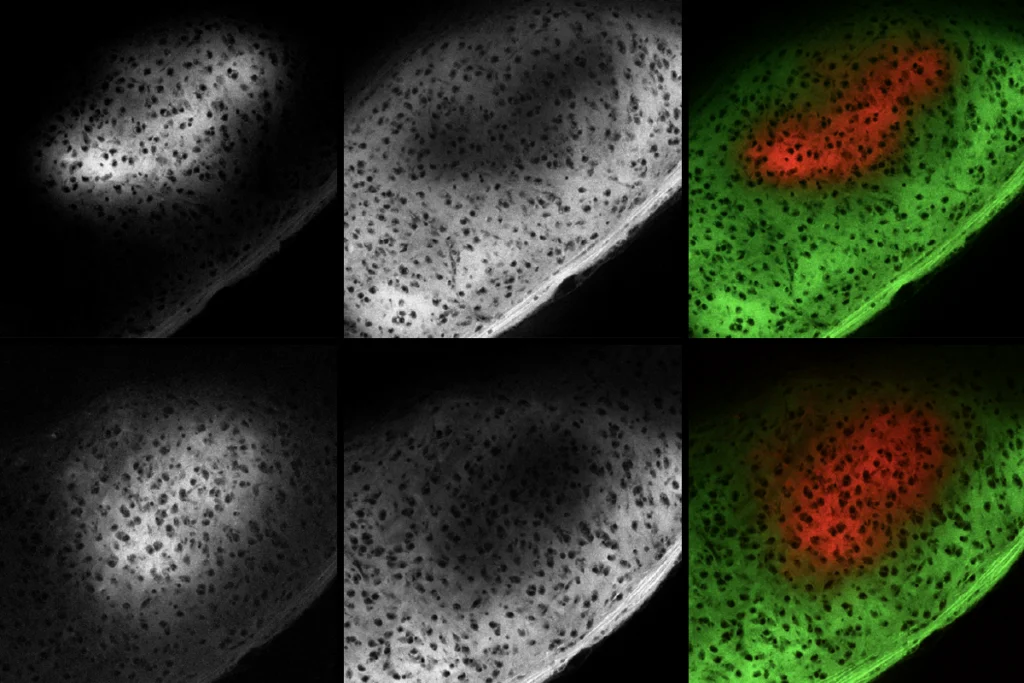

Microglia’s pruning function called into question