Unlocking the secrets of fragile X in Colombia

A remote Colombian town is home to the world’s largest cluster of people with fragile X syndrome. Scientists are learning from them — and trying to help.

This article is also available in español.

I

t’s late afternoon in Ricaurte, a tiny town tucked into the Colombian Andes, when Mercedes Triviño, 82, lights the wood stove to start preparing dinner. Smoke fills the two-bedroom home she shares with six of her adult children.Francia, 38, one of the youngest, is the family’s primary breadwinner. She brings home 28,000 Colombian pesos (roughly $10) a day harvesting papayas in the fields just outside town. “Really, what I earn is just enough for eating and nothing else,” she says. Four of her siblings have fragile X syndrome, a genetic condition that causes intellectual disability, physical abnormalities and, often, autism. Jair, 57, works alongside Francia when he can. Hector, 45, is also somewhat able to care for himself. But Victor, 55, and Joanna, 35 — who has both fragile X and Down syndrome — are less independent.

As Mercedes serves coffee on this afternoon in July, sweetening it with a hefty dose of sugar and offering her best cups to her guests, she talks about the condition that dominates the lives of her family and many others in Ricaurte. Her niece, Patricia, 48, who lives a few blocks away, cares for two adult sons and a nephew with fragile X. More distant kin in town, the Quinteros, also have grown children with the condition. Other neighbors are adults with fragile X who have no caretaker and do their best to look after one another.

In Colombia, Ricaurte has long been known as the home of los bobos — ‘the foolish ones’ — thanks in part to a 1980s novel and subsequent television series that depicted families like the Triviños. More recently, scientists have caught on to the fact that the town is home to what may be the world’s largest cluster of people with fragile X. One researcher in particular, medical geneticist Wilmar Saldarriaga-Gil of Universidad del Valle in Cali, Colombia, has made Ricaurte the focal point of his scientific inquiry. Saldarriaga-Gil, who vacationed nearby as a child, says he has visited the town about 100 times since the mid-1990s to trace the impact of fragile X on its inhabitants — and to try to understand the condition’s biology.

“This is a history of scientific research, a history of my community, a history of my life,” he says.

The payoff from research in this town could have a global impact. Caused by mutations in a gene called FMR1 on the X chromosome, fragile X syndrome is the leading cause of inherited intellectual disability worldwide; it affects as many as 1 in 2,000 men and 1 in 4,000 women. And as a single-gene cause of autism — a recalcitrantly complex condition — it has been the focus of drug development efforts in autism. The proteins disrupted in people with the syndrome are also key players in brain development.

In March, Saldarriaga-Gil and his colleagues reported that at least 5 percent of the town’s residents carry either the full-blown fragile X mutation or less severe ‘premutations’ that can trigger the condition in future generations. Premutation carriers usually escape cognitive problems, but some develop physical symptoms, including tremors and fertility problems. The research in Ricaurte might explain such variability, which could reflect how the protein FMR1 encodes, FMRP, interacts with other proteins and pathways.

The scale of Saldarriaga-Gil’s investigations is small — Ricaurte has only 58 full mutation and premutation carriers, by his count — but the research benefits from the fact that the town’s residents share the same environment and a similar genetic background, offering a natural control for some variables. “What you have [in Ricaurte],” says Jim Grigsby, professor of psychology and medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, who is not involved in the research, “is something that certainly warrants a lot more intensive investigation.”

Heavy burden: Four of Mercedes Triviño’s children have fragile X syndrome.

Premutation puzzle:

S

aldarriaga-Gil’s obsession with Ricaurte began in 1980. As a boy, he spent summers at a family home in Huasano, 10 kilometers away. When he attended church in Ricaurte, he couldn’t help but notice the lanky men and women with large, flat ears who spoke very little or not at all. “Everyone who knows Ricaurte had curiosity,” Saldarriaga-Gil says. “Why is it happening here?”Growing up, he heard many stories. According to one, nearby magnesium mines had poisoned Ricaurte’s groundwater, damaging the minds of people who drank it. Protestant missionaries to the region warned residents that God had sent ‘the foolishness’ to punish them for worshiping ‘El Divino,’ an image of Jesus in Ricaurte’s white A-frame church that draws Catholic pilgrims.

“The other hypothesis was sorcery of some sort,” Saldarriaga-Gil says. In that version, women in the town prepared a love potion that sometimes went wrong, producing intellectual disability instead of undying devotion. Saldarriaga-Gil’s father warned him never to drink anything offered by a woman from Ricaurte.

Saldarriaga-Gil eventually set out to discover the truth as a medical student in the late 1990s. His adviser suggested the people in Ricaurte might have Down syndrome. But when Saldarriaga-Gil leafed through a 1,000-page medical textbook, he saw photographs of people who looked eerily similar to a boy he knew in Ricaurte — Patricia Triviño’s nephew Ronald. The people in the textbook had fragile X syndrome.

To confirm that the resemblance was more than coincidence, in 1997 Saldarriaga-Gil took blood samples from 28 people in town he suspected were affected, Ronald included. He analyzed each person’s karyotype — the number and appearance of their chromosomes — by inspecting their blood cells under a microscope.

In most people, the FMR1 gene contains anywhere from 6 to 54 repeats of a specific set of three DNA ‘letters,’ or bases: CGG. In people with fragile X syndrome, however, the gene has more than 200 repeats. The extra DNA disrupts the X chromosome; under the microscope, tiny islands appear to break away from the chromosome, causing it to appear fragile. Of the 28 people whose karyotypes Saldarriaga-Gil analyzed, 19 showed these telltale islands.

”“When I first visited this town, I said, ‘Oh my God, this is like ground zero for fragile X.’” Randi Hagerman

Premutation carriers, however, have too few CGG repeats — somewhere between 55 and 200 — to be obvious under a microscope. In 2012, Saldarriaga-Gil decided to try to identify these carriers as well by building a pedigree chart to trace the condition’s inheritance through Ricaurte’s families. Premutation carriers often have affected children or grandchildren because in fragile X — as in other ‘triplet repeat’ conditions, such as Huntington’s disease — the number of repeats typically increases with successive generations. Working backward from affected individuals, Saldarriaga-Gil tried to guess at who had passed the mutation on. That approach only took him so far, however, as he had no definitive test for premutations.

The following year, his karyotype research caught the attention of experts in fragile X, including Randi Hagerman, medical director of the MIND Institute at the University of California, Davis. Hagerman and her colleagues offered to help Saldarriaga-Gil spot the premutation carriers by using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test — which Saldarriaga-Gil wasn’t equipped to do in his own lab. PCR would make it possible to amplify and sequence the residents’ DNA.

Hagerman recalls being struck by Ricaurte’s promise for studying fragile X: “When I first visited this town, I was surrounded by individuals with fragile X syndrome, and I said, ‘Oh my God, this is like ground zero for fragile X.’”

Close ties: Medical geneticist Wilmar Saldarriaga-Gil (right) has been studying the people in Ricaurte, including Julieta Triviño (left), for two decades.

Genetic quest:

T

he two-lane road to Ricaurte from Cali traverses sugarcane fields between the cloud-shrouded Andes, which enclose the town. Saldarriaga-Gil estimates he has driven the route dozens of times in the past five years. Before 2010, Colombia’s drug trade made the trip dangerous. The region is safer now, he says, but the mountains still teem with farmers secretly growing coca, the raw material of cocaine.Saldarriaga-Gil checks in on residents with fragile X every two months or so, offering routine checkups and monitoring them for complications. Over multiple visits between 2015 and 2016, he and his students were also able to collect blood samples from 926 people, about 80 percent of the population. Genetic analysis of the samples led to his recent finding that about 5 percent of Ricaurte’s residents have either the full mutation or a premutation. He supplemented the genetic work by recording oral histories and digging up centuries-old land, marriage and birth records with help from a local historian. In the end, Saldarriaga-Gil was able to reconstruct much of the history of the syndrome in Ricaurte.

His unwieldy pedigree chart now dominates one of his office walls, spanning nine generations and 420 names. Two big families — the Triviños and Gordillos — form its trunk. Saldarriaga-Gil slashes lines through the deceased and scrawls notes in looping handwriting where he is still guessing at kinship.

One name is circled, with sunlike rays extending out in every direction: Manuel Triviño, who may be Mercedes’ great-grandfather. Saldarriaga-Gil says he suspects Manuel was one of the town’s original settlers in the early 1880s and carried the premutation to Ricaurte. Everyone in town with fragile X could be his direct descendant (although it’s still unclear how the mutation spread to the Gordillos). To confirm this ‘founder effect,’ Saldarriaga-Gil’s team is conducting a ‘haplotype analysis’: They are looking for other genetic variants shared by residents with the condition, which would imply they all share a common forebear.

Founder effect: Everyone in Ricaurte who has fragile X, including Hector (second from left) and Victor (second from right) Triviño, may be descended from a common ancestor.

Distinct profiles:

H

e and colleagues from his university in Cali are also sequencing the exomes — the protein-coding portions of the genome — of the people from whom they took blood samples in 2015. They hope to learn how genetic variability outside the FMR1 gene influences how fragile X mutations manifest themselves — and why people with the same FMR1 mutations can have such different outcomes.Among women, ‘mosaicism’ — in which a person’s cells aren’t all genetically identical — is part of the explanation. Because women have two X chromosomes, each cell turns off one of them, at random. If most of a woman’s cells turn off the mutated copy, she might show few outward signs of the mutation; if the normal copy is shut down more often, she might be more severely affected. Mosaicism emerges differently in men, who have a single X chromosome: Some of their cells may have the full FMR1 mutation —200-plus CGG repeats — whereas others end up with the shorter premutation or with a complete deletion of the FMR1 gene.

The array of symptoms resulting from a mutation might also depend on how FMRP interacts with other proteins. FMRP is missing in people with the full mutation, which silences the gene. Because FMRP controls the activity of nearly 1,000 other proteins, many of which are crucial to the interactions between neurons, its loss can have far-reaching effects, particularly during brain development. But in people with the premutation, the impact of the reduced protein might be more or less severe depending on other genetic variations.

”“Everyone who knows Ricaurte had curiosity. Why is it happening here?” Wilmar Saldarriaga-Gil

Saldarriaga-Gil and his colleagues predict their genetic analyses will reveal that people whose fragile X symptoms are similar have overlapping patterns of gene expression and protein interaction. “This type of population is ideal for this study because these people have a similar genetic background,” says geneticist Julián Andrés Ramírez Cheyne of Universidad del Valle in Cali, who is leading the exome study.

The ultimate goal for fragile X researchers is to develop treatments that help people with the syndrome. Because of its connection to intellectual disability and autism, fragile X has been the focus of an extensive — and so far unsuccessful — drug development program. Several candidates that showed promise in early clinical trials fizzled out in larger trials. Researchers are seeking new proteins or pathways to target — and some of those may emerge from the work in Ricaurte. “Most geneticists would say there are genetic modifiers in some of these families,” says Eric Klann, director of the Center for Neural Science at New York University — clues, he says, to possible treatments.

Understanding the molecular underpinnings of fragile X might also explain why general anesthesia and some seizure medications are more toxic to premutation carriers than to typical people. Hagerman says she was struck by the number of premutation carriers in Ricaurte whose symptoms are unusually severe. Patricia Triviño’s sister Rosaura, 60, for example, is deaf and mute; her sister Julieta, 58, has seizures and uses a wheelchair. Hagerman says pesticides, sprayed heavily in the nearby fields, might be to blame. “Looking at the environmental contaminants could tell us a lot about vulnerability” in people with both the pre- and the full mutation, she says.

Hard worker: Jair Triviño, 57, has fragile X syndrome and labors long hours harvesting fruit.

Ticking clock:

I

n Ricaurte, no one is waiting for radical new treatments. Even if the residents can help researchers develop drugs, they know they are likely to be among the last to receive them.At nearly 60, Mercedes Triviño’s son Jair is one of the oldest workers in the papaya fields, but he has no complaints. Even though his work is arduous, living in Ricaurte among others with similar symptoms has given him a degree of freedom he’d be hard-pressed to find anywhere else. At the end of his shift on a hot July day, Jair fills the back of a pickup truck with fruit. He swings the heavy crates one by one, his wiry arms flexing until he has stacked nearly 100. He stops to wipe sweat from his brow and secures the truck’s door with an iron bolt. The driver starts the engine as Jair hops in the back. Jair says he looks forward to being back the next day, “if it’s God’s wish.”

Back in town, Patricia Triviño, Jair’s cousin, says all she wants is a good drug to control the seizures of her sister Julieta.

For years, Julieta has taken phenobarbital to control her convulsions, but the drug is risky for premutation carriers like her, who may be particularly vulnerable to its neurotoxic effects. Scans Saldarriaga-Gil took show that portions of Julieta’s brain have shrunk, and in the past few weeks, she has started complaining of headaches. Another one of Patricia’s sisters, Esperanza, who was also a premutation carrier and relied on phenobarbital for years, died in 2015 after several massive seizures. There are safer medications Julieta could take, such as valproate. But she has had trouble getting a prescription.

In July, a new doctor who serves Ricuarte as well as three other local towns arrives to make her rounds. Rubbing Julieta’s temples below her cropped black hair, the doctor explains that she cannot prescribe valproate because she doesn’t have the correct paperwork. She suggests Patricia take Julieta to see another doctor in the neighboring town of Bolívar, about 7 kilometers away. Patricia doesn’t own a car, and it would take her about an hour and a half to walk there.

For months, Patricia has pleaded with a local health minister, Viviana Alvarez, to secure basic sanitary supplies and protein supplements for Julieta — but to no avail. The family is entitled to free care through the government, but Alvarez says her hands are tied: “Health insurance takes its time; the problem is on the national level.” The Hospital Santa Ana in Bolívar can’t help much either. With just eight doctors, it fielded 15,000 appointments and 5,000 emergency room visits in 2017. The hospital director, Carlos Dávalos, has hired a physical therapist to visit about 15 people with fragile X in Ricaurte every weekday, but he says the town will probably never have its own physician.

“I always want them to do more,” says Saldarriaga-Gil, although he understands the financial constraints. He says he tries to fill in the gaps during his visits and has enlisted a Colombian nonprofit to donate clothes and mattresses to many of the families.

Given the harsh realities of life in Ricaurte with fragile X, some residents have made difficult decisions about the future of their families. Rosario Quintero’s daughter, Sara, has the full mutation but shows no signs of the syndrome. Before Sara learned she carries the mutation, she had a son, who also seems to be unaffected. But afterward, she had her fallopian tubes cut so she cannot have any more children. Another carrier, who chose to remain anonymous, also decided to not have children.

Over the past decade, only three children with fragile X have been born in Ricaurte, and many with the condition are older than 50. Trapped in this valley by economic hardship and unyielding geography, the population with fragile X could slowly die out, Saldarriaga-Gil says. He is racing to understand the syndrome’s secrets before that happens.

This story was produced in collaboration with Science.

On a deadline: Scientists hope to unlock fragile X’s secrets before the population here dies out.

This article was republished in El Espectador.

Explore more from The Transmitter

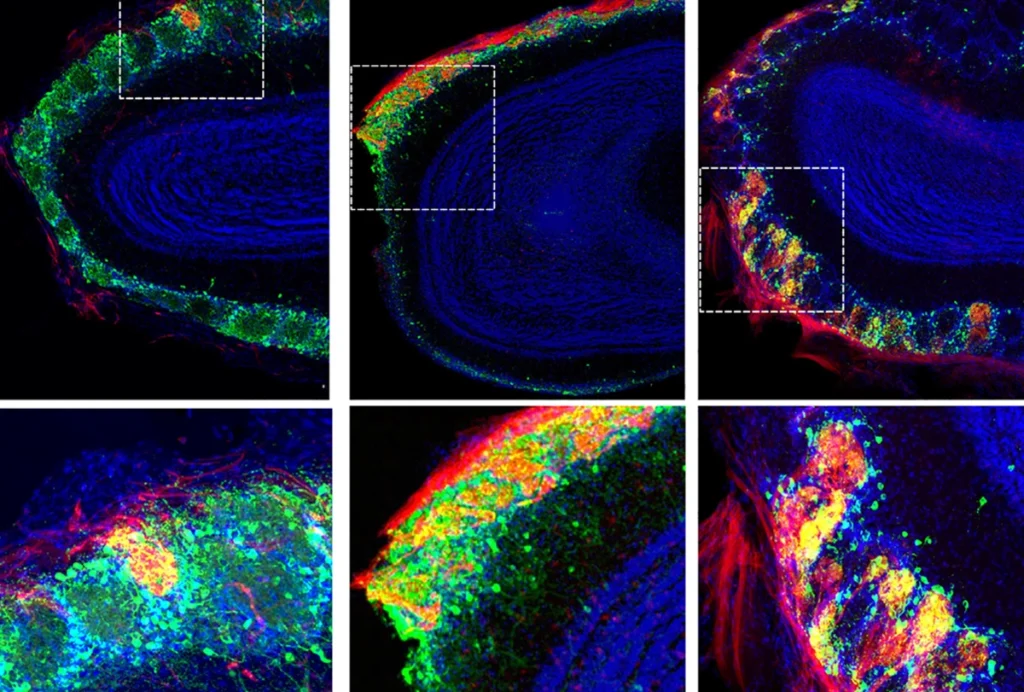

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’