Untangling the ties between autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder

Autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder frequently accompany each other; Scientists are studying both to understand how they differ.

S

teve Slavin was 48 years old when a visit to a psychologist’s office sent him down an unexpected path. At the time, he was a father of two with a career in the music industry, composing scores for advertisements and chart toppers. But he was having a difficult year. He had fewer clients than usual, his mother had been diagnosed with cancer, and he was battling anxiety and depression, leading him to shutter his recording studio.Slavin’s anxiety — which often manifested as negative thoughts and routines characteristic of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) — was nothing new. As a child, he had often felt compelled to swallow an even number of times before entering a room, or to swallow and count — one foot in the air — to four, six or eight before stepping on a paving stone. As an adult, he frequently became distressed in crowds, and he washed his hands over and over to avoid being contaminated by other people’s germs or personalities. His depression, too, was familiar — and had caused him to withdraw from friends and colleagues.

This time, as Slavin’s depression and anxiety worsened, his doctor referred him to a psychologist. “I had had an appointment booked for weeks and weeks and months,” he recalls. But about 10 minutes into his first session, the psychologist suddenly changed course: Instead of continuing to ask him about his childhood or existing mental-health issues, she wanted to know whether anyone had ever talked to him about autism.

By coincidence, a relative had mentioned autism to Slavin two days prior, wondering if it might explain why he dislikes social situations. Slavin knew little about the condition but had conceded it was possible. By the time his therapy session ended, his psychologist was almost certain: “She said to me that I’ve either got high-functioning autism or some kind of brain damage,” Slavin recalls with a chuckle. Only a few years earlier, a doctor had finally diagnosed him with OCD. His new psychologist diagnosed him with autism as well.

At first glance, autism and OCD appear to have little in common. Yet clinicians and researchers have found an overlap between the two. Studies indicate that up to 84 percent of autistic people have some form of anxiety; as much as 17 percent may specifically have OCD. And an even larger proportion of people with OCD may also have undiagnosed autism, according to one 2017 study.

Part of that overlap may reflect misdiagnoses: OCD rituals can resemble the repetitive behaviors common in autism, and vice versa. But it’s increasingly evident that many people, like Slavin, have both conditions. People with autism are twice as likely as those without to be diagnosed with OCD later in life, according to a 2015 study that tracked the health records of nearly 3.4 million people in Denmark over 18 years. Similarly, people with OCD are four times as likely as typical individuals to later be diagnosed with autism, according to the same study.

In the past decade, researchers have begun to study these two conditions together to work out how they interact — and how they differ. Those distinctions could be important not only for making correct diagnoses but also for choosing effective treatments. People who have both OCD and autism appear to have unique experiences, distinct from those of either condition on its own. And for these people, standard interventions for OCD, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), may provide little relief.

”“It’s complicated to tease out anxiety from autism.” Roma Vasa

Missed diagnoses:

O

bsessions and compulsions can strike anyone: It’s common to worry about having left the oven on or to rifle anxiously through a purse in search of keys. “They’re really part of the normal experience,” says Ailsa Russell, clinical psychologist at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom. Most people find ways to dismiss those unpleasant thoughts and move on. Among people with OCD, though, those worries build up over time and disrupt daily functioning.Some people, like Slavin, count steps or breaths to quell their terror that something bad will happen. Others describe themselves as ‘checkers,’ who investigate — again and again — that they’ve done a task properly. Still others are ‘cleaners,’ who wash constantly in response to a fear of filth and contamination. “Mostly, people with OCD realize it’s not that rational,” Russell says, but feel trapped by their worries and rituals.

The overlap between OCD and autism is still unclear. People with either condition may have unusual responses to sensory experiences, according to a 2015 analysis. Some autistic people find that sensory overload can readily lead to distress and anxiety. Slavin, for example, dreads police sirens and the peal of doorbells, which he likens to a bomb exploding in his nervous system. Some researchers say the social problems people with autism experience may contribute to their anxiety, which is also a component of OCD. Not being able to read social cues might lead people to become isolated or be bullied, fueling anxiety, the reasoning goes. “It’s complicated to tease out anxiety from autism,” says Roma Vasa, director of psychiatric services at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

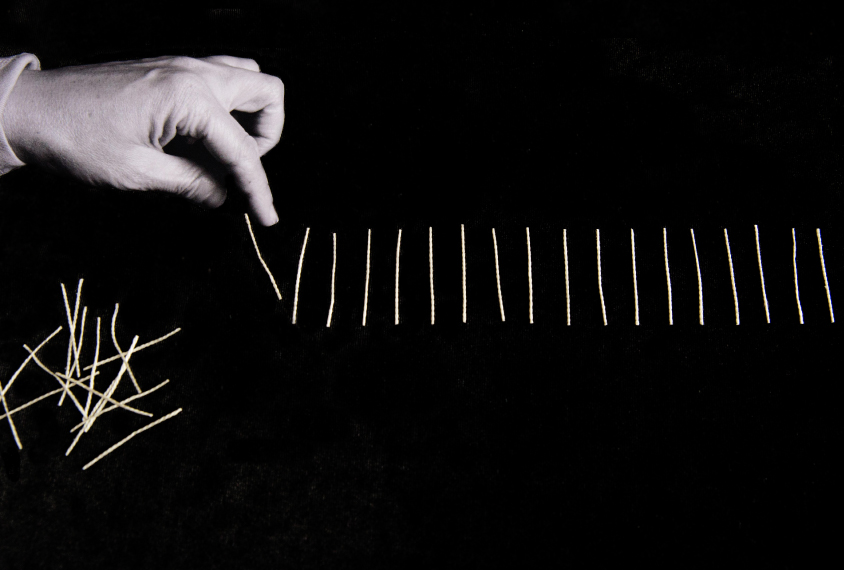

These shared traits make autism and OCD difficult to distinguish. Even to a trained clinician’s eye, OCD’s compulsions can resemble the ‘insistence on sameness’ or repetitive behaviors many autistic people show, including tapping, ordering objects and always traveling by the same route. Untangling the two requires careful work.

One crucial distinction, the 2015 analysis found, is that obsessions spark compulsions but not autism traits. Another is that people with OCD cannot swap the specific rituals they need, Vasa says: “They have a need to do things a certain way, otherwise they feel very anxious and uncomfortable.” By contrast, autistic people often have a repertoire of repetitive behaviors to choose from. “They’re just looking for anything that’s soothing; they’re not looking for a particular behavior,” says Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University.

Clinicians, then, have to probe why a person engages in a particular action. That task is doubly difficult if the person cannot articulate her experience. Autistic people may lack self-insight or have verbal, communicative or intellectual challenges, which leads to misdiagnoses and missed diagnoses, like Slavin’s.

Clinicians long overlooked Slavin’s OCD and autism, although he was no stranger to a psychologist’s office growing up in the suburbs of northwest London. He did not speak for his first six years and says his memories are peppered with frequent visits to speech therapists and psychiatrists. Even after he began talking, he was socially withdrawn and disliked eye contact. He was plagued with anxieties and stomachaches.

At around 11, he was diagnosed with ‘infantile schizophrenia’ and prescribed valium and lithium. Doctors warned his parents that he might need to be institutionalized for life. Instead, he attended a progressive boarding school and graduated, as he puts it, a “slightly more functional” person. He pursued his passion for music, met his wife Bonnie and started a family.

His autism diagnosis so many years later was empowering, he says, but it also raised new complications. When he spoke with clinicians, for example, his autism always seemed to eclipse his other challenges, including an auditory-processing disorder. “Once you’ve had a diagnosis of autism, doctors say ‘Oh, it’s because of the autism,’ and they don’t look at the nuances,” he says. He found that no one could tell him whether a particular behavior was a result of his OCD or his autism — or what to do about it.

Common biology:

A

nswers to Slavin’s questions may emerge as more researchers study autism and OCD together. Just 10 years ago, virtually no one did that, says Suma Jacob, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. When she told people she was interested in researching both conditions, “top advisers in the field said you have to pick one,” she says. That’s changing, in part because researchers have come to appreciate how many people have both conditions.Jacob and her colleagues are tracking the appearance of repetitive behaviors — which could be linked to autism or OCD — by age 3 in thousands of children. “From the brain perspective, these [conditions] are all related,” she says.

In fact, scientists have found some of the same pathways and brain regions to be important in both autism and OCD. Brain imaging points to the striatum in particular, a region associated with motor function and rewards. Some studies suggest that people with autism and people with OCD both have an unusually large caudate nucleus, a structure within the striatum.

Animal models, too, implicate the striatum. Veenstra-VanderWeele is studying autism and OCD using rodents that show repetitive behaviors. In both conditions, he and other neuroscientists have found anomalies within the brain’s cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical loop; this system of neural circuits runs through the striatum and plays a part in how we start and stop a behavior, as well as in habit formation. Another line of inquiry highlights interneurons, which often inhibit electrical impulses between cells: Disrupting interneurons in the striatum can create twitching, anxiety and repetitive behaviors in mice that appear similar to traits of OCD or Tourette syndrome.

Among male mice specifically, interfering with interneurons in the striatum also leads to sharp drops in social interaction, forging a tenuous connection to autism. “Lo and behold, the mice also had social deficits identical to what we’ve seen in [animal models] associated with autism,” says Christopher Pittenger, director of the OCD Research Clinic at Yale University, who led this work. For that reason, he says, interneurons might be a common treatment target for both autism and OCD.

Some of the shared wiring researchers are uncovering could reflect a genetic overlap. The 2015 Danish study found that people with autism are more likely than controls to have relatives with OCD. But genetic comparisons of the two conditions thus far have yielded contradictory results or been hampered by how little is known about the genetics of OCD. “We know much more about the genetics of autism than we do about OCD, almost embarrassingly so,” Pittenger says. That gap could explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies — encompassing more than 200,000 people with 25 conditions, including autism and OCD — found no shared common variants between OCD and autism.

Unpublished work from another group suggests that rare ‘de novo mutations,’ which occur spontaneously, can significantly increase the risk of having autism or OCD. Some of the genes the researchers linked to both diagnoses relate to immune functioning, suggesting that an interaction between environmental factors and the immune system might play a role. Another gene on that shared list, CHD8, regulates gene expression.

”“We know much more about the genetics of autism than we do about OCD, almost embarrassingly so.” Christopher Pittenger

Adapting treatment:

U

ntil scientists can connect these preliminary findings to pathways, new drug treatments are a long way off. But people who have both conditions do have other routes for finding help.On a chill evening in December, people across the U.K. dial in to a monthly ‘OCD & Autism Support Group’ meeting organized by OCD Action, a U.K.-based charity for people with OCD. The group size varies from one session to the next, but on this particular night, just days before Christmas, there are only four callers.

During the session, a woman named Michelle (everyone on the call uses first names only) explains that she cannot leave the house unless she is convinced all the switches and appliances are turned off. Thomas loses hours of the day to showering. Both talk about social difficulties — and how that can make them anxious. They often worry about what people think of them and whether their repetitive behaviors, caused by OCD or autism, make them appear strange to others.

As with most support-group meetings, the call reassures its participants that they are not alone. The callers also share updates and tips, such as using a timer to cut down on the time spent on hand-washing. Three of the callers mention CBT, which can help people understand and manage their obsessions and compulsions. As with other talk therapies, though, CBT isn’t always effective for people with autism. The therapy did not help Slavin, for example.

He suspects that he was unable to follow his therapist’s approach due to his auditory-processing difficulties and cognitive inflexibility, which he attributes to his autism. “Many people on the spectrum have a problem picturing a situation and picturing how it could have a different outcome, so traditional CBT doesn’t always work,” he says. Slavin instead manages his OCD — with mixed success — using antidepressants.

Some researchers are trying to adapt CBT for people with autism by, among other things, “making sure that somebody can notice and rate their emotional state,” Russell says. Working with her colleagues at King’s College London, Russell found in a pilot study that the modified methods help some adults with both autism and OCD manage their anxiety. Drawing on the success of a subsequent larger trial, she and her colleagues published a guide for clinicians in January.

A more personalized variation of CBT might also work for people who have both autism and OCD. Various schemes include involving parents in sessions, adjusting the language to meet an autistic person’s ability, using visuals and offering children rewards. One trial is comparing these adaptations with standard CBT in more than 160 children who have both autism and OCD. The unpublished results suggest that standard CBT is beneficial, but an individualized approach is best of all.

Slavin sees the merits of more personalized treatment options, although he hasn’t tried it himself. Working with OCD Action and nonprofit advocacy groups for autism, he has come to appreciate the diversity that exists in both conditions. “It’s almost like you need a different diagnosis for every single person, a different category for every single person, because everyone is so different,” he says.

A decade after his autism diagnosis, Slavin is eager to share his experiences, in part to counteract the lack of resources he initially faced. In 2010, he launched a website and, later, a YouTube series to describe what he has learned about life with autism.

“I just see [autism] as a set of circumstances that you can use to your benefit to say ‘Okay, I’m going to forgive myself if I don’t quite understand things in the way other people do,’” Slavin says. “You can almost enjoy being a bit quirky, a bit different in some ways … [but] OCD, there’s just nothing good about that.”

In October, he published a book that chronicles the progress he has made. For now, at least, the book’s title begins: “Looking for Normal.”

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Machine learning spots neural progenitors in adult human brains

Xiao-Jing Wang outlines the future of theoretical neuroscience