This paper changed my life: John Tuthill reflects on the subjectivity of selfhood

Wittlinger, Wehner and Wolf’s 2006 “stilts and stumps” Science paper revealed how ants pull off extraordinary feats of navigation using a biological odometer, and it inspired Tuthill to consider how other insects sense their own bodies.

Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

What paper changed your life?

The ant odometer: Stepping on stilts and stumps. Wittlinger M., Wehner R., Wolf H. Science (2006)

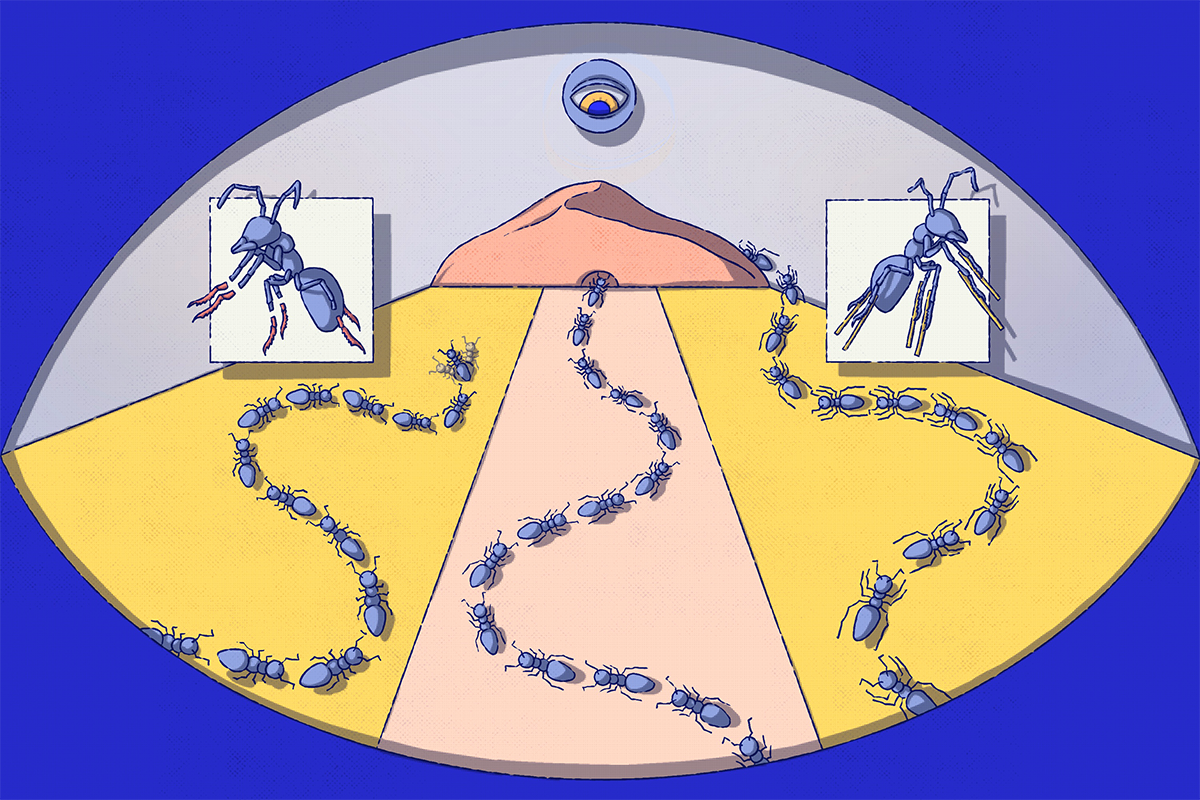

A solitary ant zigzags for hours through the blazing, featureless Sahara Desert, scavenging for food. When it comes across the corpse of a less hardy insect, the ant picks it up and makes a beeline directly back to the cool shade of its nest. After such a long, torturous search, and in the absence of obvious visual landmarks, how does the ant find its way straight back home?

Theoretically, this form of navigation, called path integration, requires measuring two quantities: steering direction and distance traveled. Prior work had shown that insects can measure their direction with a celestial compass based on the sun and polarization pattern of the sky. Matthias Wittlinger, Rüdiger Wehner and Harald Wolf were the first to fill in the second piece of the puzzle, revealing that desert ants possess the capacity to keep track of distance—an internal odometer.

The single experiment in this paper is satisfyingly simple. Just after each foraging ant found a snack, the authors caught it and manipulated the length of its legs so that it would be forced to take longer or shorter strides on its journey back to the nest. Whereas ants with shortened legs (stumps) undershot the nest location, those with elongated legs (stilts) overshot. These striking and clear results suggest that the ants track the number of steps they take when they set out to forage. They then somehow combine their step count with the celestial compass to calculate the precise distance and direction back to the nest. This “stilts and stumps” experiment was the first to provide convincing evidence for a biological odometer in any animal.

When did you first encounter this paper?

I stumbled across this paper while rummaging through a hard copy of Science in the dining hall of Friday Harbor Labs—the University of Washington’s marine lab, located in the barnacle-crusted San Juan Islands of Puget Sound. I had recently graduated from college and was participating in one of the lab’s summer research apprenticeship programs. Unlike so many of the other papers I encountered as an aspiring scientist, this one described an experiment I could imagine doing with my own hands.

Why is this paper meaningful to you?

As a kid, I loved reading stories of humans surviving extreme conditions. The people in these stories usually ended up in bad situations due to a lack of knowledge or preparation but survived by performing incredible feats of navigation, such as Ernest Shackleton’s last-ditch lifeboat journey to South Georgia or Slavomir Rawicz’s long walk across the Gobi Desert.

The average desert ant, Cataglyphis fortis, exceeds the fortitude of even the toughest Victorian explorer. These insects live in one of the most inhospitable places on Earth: the barren, sun-scorched salt pans of North Africa. Every time a desert ant leaves the nest to forage, it is like an ill-fated 19th century expedition; their daily mortality rate is around 15 percent. Desert ants have evolved extraordinary navigational capacities that allow them to live right on the precipice of survival. I have immense respect for these rugged creatures.

How did this research change how you think about neuroscience and influence your scientific trajectory?

Reading this paper made me consider, for the first time, how insects sense their own bodies. In college, I learned about proprioception from a physical therapist after sustaining a severe table-saw injury to my thumb. I also became fascinated by the subjectivity of sensory perception, particularly how some animals perceive aspects of their environment that are invisible to us, such as polarized light. Finally, I attended an inspiring lecture by fly biologist Michael Dickinson, which sparked my interest in insect neuroethology. The stilts and stumps paper brought these together. It made me wonder: What does it feel like to be a foraging ant running through a scorching hellscape, completely reliant on an internal odometer to find the way back home? The desire to understand what it feels like inside a different animal’s body and brain has motivated much of my scientific work.

Learning about the incredible biological adaptations of the desert ant later inspired me to study an equally rugged insect: the snow fly, Chionea, a wingless crane fly that has evolved to live in snowy, alpine environments, such as the Cascade Mountains here in Washington. In a recent paper, we showed that snow flies can sustain locomotor behavior at internal body temperatures down to minus 10 degrees Celsius. Neurons in other animals shut down below zero, so how snow flies achieve this remains a mystery. In that study, we also discovered that when a snow fly’s leg freezes, it self-amputates the leg to prevent ice from spreading to its internal organs. Like desert ants, snow flies benefit from living in such harsh conditions; reduced predation enables them to serenely wander the snow in search of mates. My hope is that, just as work on desert ants has revealed adaptations to extreme heat, studying snow flies will reveal how biological systems have adapted to sustain life at the opposite extreme.

Is there an underappreciated aspect of this paper you think other neuroscientists should know about?

The stilts and stumps experiment is reasonably well known, but the number of redundant mechanisms that desert ants (and other animals) can rely on for navigation is less appreciated. Cataglyphis ants, for example, integrate directional information from skylight cues, wind direction and the Earth’s geomagnetic field. They can track distance using both step-counting and self-induced optic flow. Cataglyphis ants can effectively path-integrate back to their nests even while walking backward and dragging loads 10 times their body weight. Remarkably, they can estimate distance even when they are carried by their nestmates, as long as they can see the sky. Evolution has prepared desert ants to handle nearly any situation that nature comes up with. They are the Inspector Gadgets of the Sahara.

What new progress has been made since this paper was published?

Back when I first read this paper, nearly 20 years ago, little was known about how the insect brain pulls off such extraordinary feats of navigation. Since then, I have been lucky to have a front-row seat to a string of profound discoveries about the neural circuits and mechanisms that support the navigational capacities of insects.

I had just finished my Ph.D. when Johannes Seelig, a postdoctoral researcher down the hall in Vivek Jayaraman’s lab at the Janelia Research Campus, made a surprising discovery. He showed that the ellipsoid body, a group of neurons in the middle of the Drosophila brain, operates as a literal ring attractor that continuously encodes the fly’s heading direction. This discovery kicked off a flurry of experimental and computational work from multiple labs that has collectively revealed how the fly head-direction signal is constructed and deployed for navigation. Now, 10 years later, we can point to the specific neurons and synapses in the Drosophila brain that perform the vector computations required for path integration. These central complex circuits appear to be conserved across arthropods, including central place foragers such as bees and ants, which perform virtuosic feats of navigation compared with fruit flies. Though the neural basis of the step-counting odometer remains elusive, this work on the head-direction system demonstrates that we can uncover the biological implementation of seemingly magical behaviors. The desert ant’s step-counting odometer—first revealed by the simple stilts and stumps experiment—remains one of my favorite unsolved neuroscience mysteries.

Explore more from The Transmitter