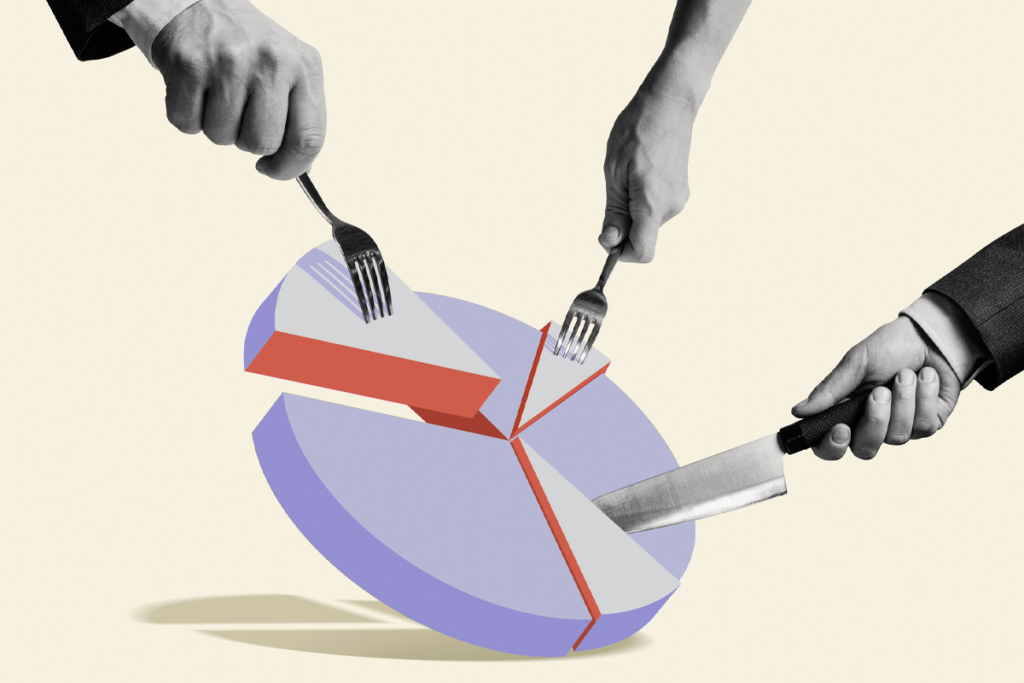

On Tuesday, the Dutch Senate voted to phase out animal research funding for the Biomedical Primate Research Centre by 2030, as part of a broader budget package. The facility has one of the largest breeding colonies of macaques in Europe.

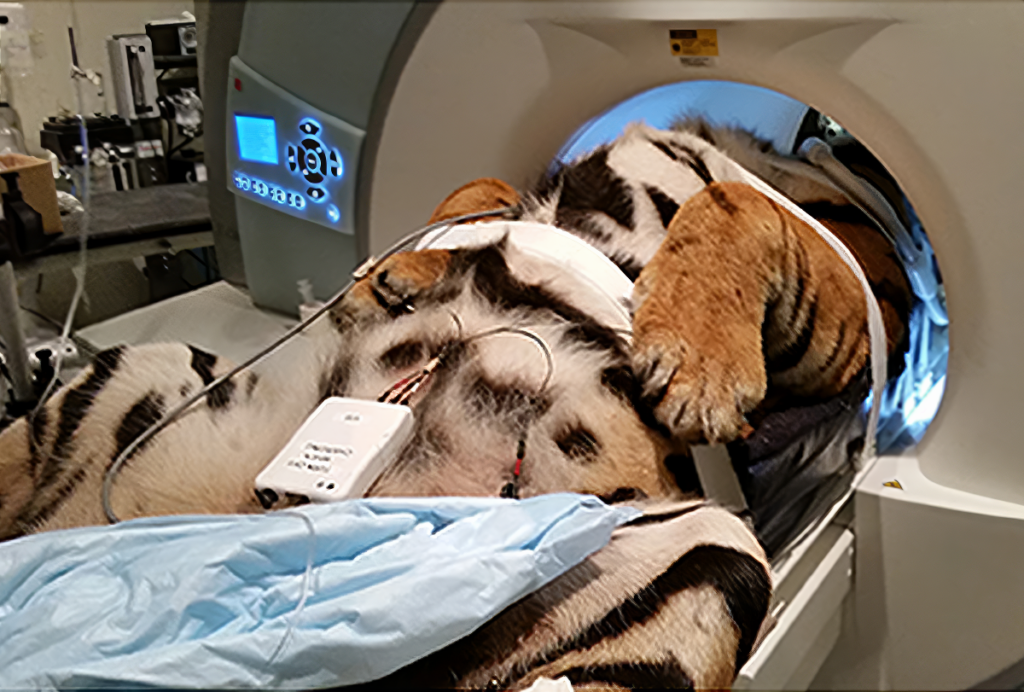

Most research at the center, based in Rijswijk, the Netherlands, focuses on infectious diseases, but neuroscientists there also study Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and the neurological effects of COVID-19, as well as conduct in-vitro, comparative genetics and data-science studies. The budget amendment requires the center, which houses about 1,000 animals, to gradually reallocate its remaining annual primate research funding—roughly 10 million euros—toward non-animal research and the development of new non-animal models. It will shift about 2 million euros per year.

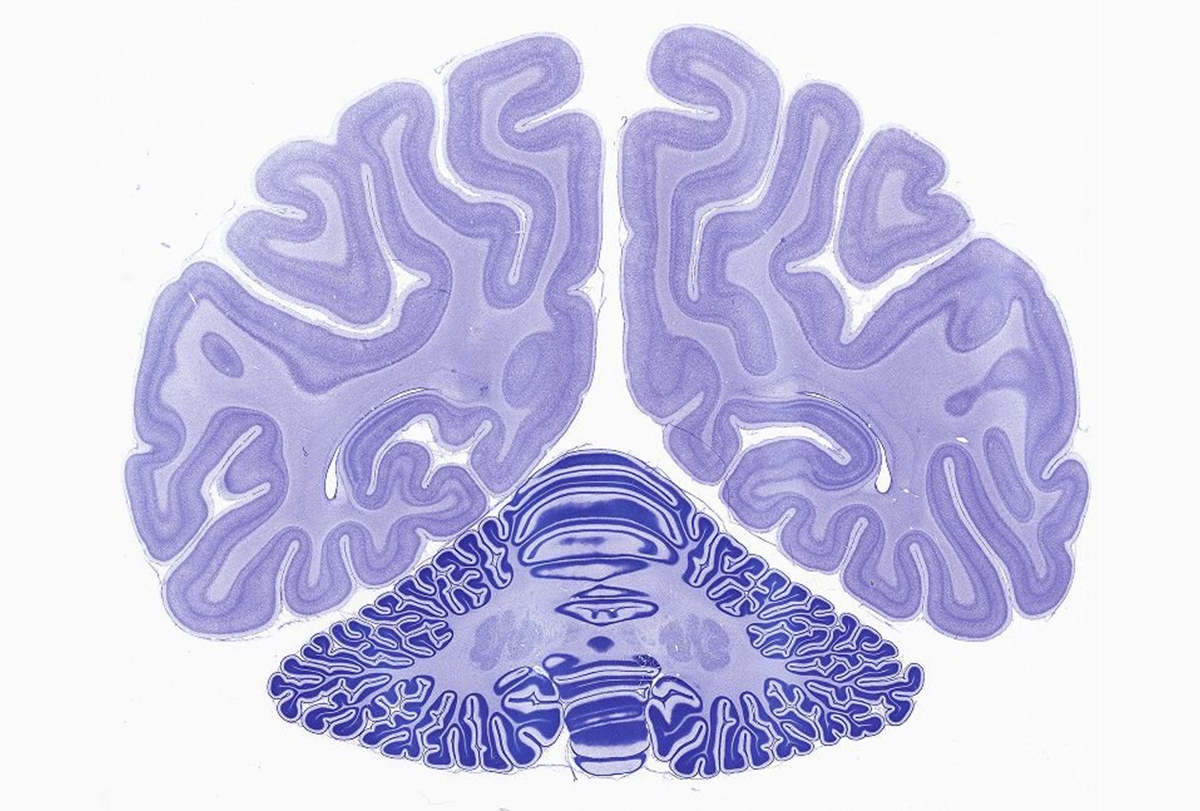

It’s “very hard to imagine how complex decision-making, how memory, attention, emotions, executive functions of the brain, can be easily simulated” outside of primates, says Stefan Treue, director of the German Primate Center and head of the Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Göttingen.

And, he adds, the strategy employed by Party for the Animals in the Netherlands, which spearheaded the policy change, could become a blueprint for banning animal research without public debate in other countries. He says it also presents a loophole in European Union rules that permit research on animals when there is no alternative.

Although the European Commission hopes to fully phase out animal research, it has been supportive of maintaining animal studies when they are irreplaceable, says Emmanuel Procyk, a research director at the Stem-Cell and Brain Institute in Lyon, France, and co-chair of EU-Simia, a network of European primate researchers in 10 countries. But shifting national politics are “very unpredictable,” he adds, noting recent moves in the United States to phase out animal research.

If the Netherlands vote is a harbinger for the rest of Europe, primate research will likely shift to other countries, such as China, says developmental biologist Pierre Savatier, also a research director at the Stem-Cell and Brain Institute. “The question is whether we want to stay behind.”

T

he amendment is tied to the budget of the Netherlands’ Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, and it initially passed the House of Representatives in July. Later that month, some senators asked for a period of debate, after a collection of European scientific and patient organizations, including the European Brain Council, wrote to the Senate, pointing to the amendment’s potentially negative effects on human health and science. In a survey after the July vote, about 87 percent of 227 researchers—and 99 percent of 80 neuroscientists—from the Netherlands said that areas of their work require the use of nonhuman primates.The outgoing minister opposed the amendment, and the new minister, who took office in September, asked that it be considered as a motion, rather than an amendment, in order to incorporate more debate. But on 2 October he pledged to implement the amendment anyway.

As the vote drew near, members of the Dutch science community rushed to provide input. The Dutch Animal Testing Information Foundation, for example, wrote to the Senate on Monday, urging it not to approve the amended budget, and stating that the phasing out within five years was unrealistic.

Others, however, expressed optimism about animal model replacements. “AI, organ on a chip, organoids—we can make them more human-relevant and more predictive for humans,” says Merel Ritskes-Hoitinga, professor of evidence-based transition to animal-free innovations at the University of Utrecht.

But animal experiments are already only allowed if they are deemed scientifically irreplaceable, says Roger Adan, professor in molecular pharmacology at University Medical Center Utrecht. This means the work at the center has already been cleared by a national committee. Adan is a member of the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies’ Committee on Animals in Research, which was a signatory to the July letter urging the Dutch Senate not to approve the budget with the amendment. “Everybody wants to get rid of animal experimentation where possible,” he adds.

Merel Langelaar, director of the Biomedical Primate Research Centre, says she plans to seek funding from private donors or a different government ministry. Regardless, neuroscience research at the center can continue in some form, thanks to its nonhuman primate brain banks, for instance, says Jinte Middeldorp, who heads the center’s Department of Neurobiology and Aging.

Losing funding for investigative research—such as a project modeling alpha-synuclein aggregation in Parkinson’s disease at the center—is a “huge problem for scientific freedom,” says Roman Stilling, a member of the Committee on Animals in Research who works in outreach at the Germany-based Understanding Animal Testing. “What this debate really shows is a misunderstanding of how science works.”