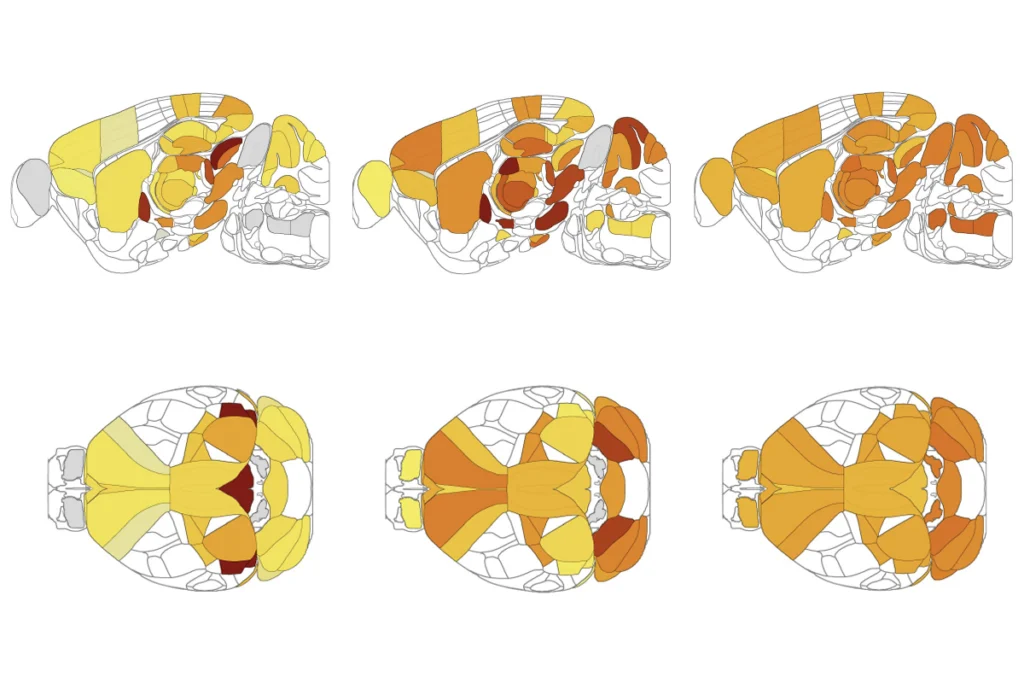

The process of making a decision engages neurons across the entire brain, according to a new mouse dataset created by an international collaboration.

“Many, many areas are recruited even for what are arguably rather simple decisions,” says Anne Churchland, professor of neurobiology at University of California, Los Angeles and one of the founding members of the collaboration, called the International Brain Laboratory (IBL).

The canonical model suggests that the activity underlying vision-dependent decisions goes from the visual thalamus to the primary visual cortex and association areas, and then possibly to the frontal cortex, Churchland says. But the new findings suggest that “maybe there’s more parallel processing and less of a straightforward circuit than we thought.”

Churchland and other scientists established the IBL in 2017 out of frustration with small-scale studies of decision-making that analyzed only one or two brain regions at a time. The IBL aimed to study how the brain integrates information and makes a decision at scale. “We came together as a large group with the realization that a large team effort could be transformative in these questions that had been kind of stymieing all of us,” Churchland says.

After years of standardizing their methods and instrumentation across the 12 participating labs, the IBL team constructed a brain-wide map of neural activity in mice as they complete a decision-making task. That map, published today in Nature, reveals that the activity associated with choices and motor actions shows up widely across the brain. The same is true for the activity underlying decisions based on prior knowledge, according to a companion paper by the same team, also published today in Nature.

The IBL labs generated the map by pooling their Neuropixels recordings from 139 mice that completed a visual discrimination task. Each lab recorded different brain areas, but together they covered the entire brain. The resulting dataset spans almost 300 brain areas and includes activity from more than 620,000 neurons, making it one the richest datasets on decision-making, says Floris de Lange, professor of brain, cognition and behavior at Radboud University, who was not involved with the study.

The IBL has made the dataset public, which de Lange says enables researchers to “test new ideas in a really easy and powerful way.”

T

he IBL selected a visual behavioral task complex enough to get at the different aspects of decision-making but simple enough to reproduce across labs.During the task, mice saw a black-and-white-striped circle appear on the left or the right side of a screen and then maneuvered a tiny wheel to center the circle on the screen. The mice received a sip of water if they succeeded and heard white noise if they failed. Electrodes recorded brain activity as mice observed the visual cue, made their choice, moved the wheel and received the water or noise feedback.

As soon as the animals saw the visual cue, activity appeared in predictable areas, including the visual cortex, the thalamus and the prefrontal cortex.