Mouse pups, like other infants across the animal kingdom, cry to get their mother’s attention. The oxytocin system drives this communication and shapes how baby mice interact when reunited with their mothers, according to a study out today in Science.

Oxytocin, known colloquially as the “love” or “cuddle” hormone, stimulates milk release during nursing and promotes maternal care behaviors. But most oxytocin research thus far has focused solely on the mother, overlooking the neuropeptide’s potential effects on an infant’s brain and behavior.

This new study shows “the other half of the equation to what we already knew,” says Zoe Donaldson, associate professor of behavioral neuroscience at the University of Colorado Boulder, who was not involved with the study. Oxytocin is “this social signal that ultimately reinforces relationships,” she says.

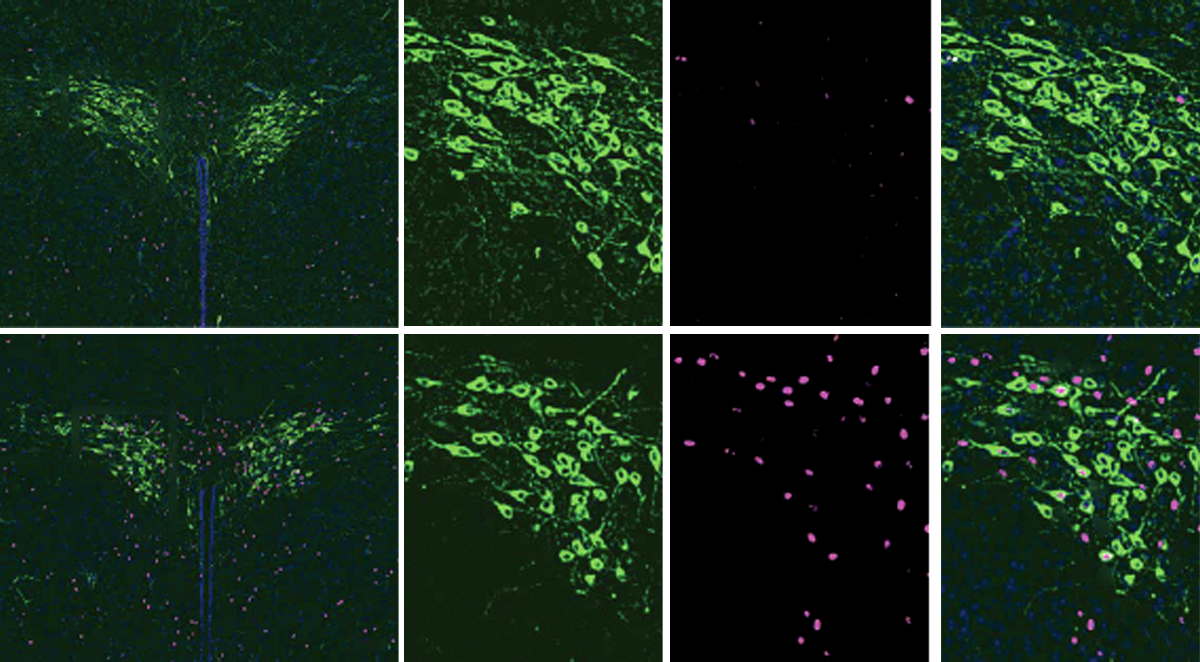

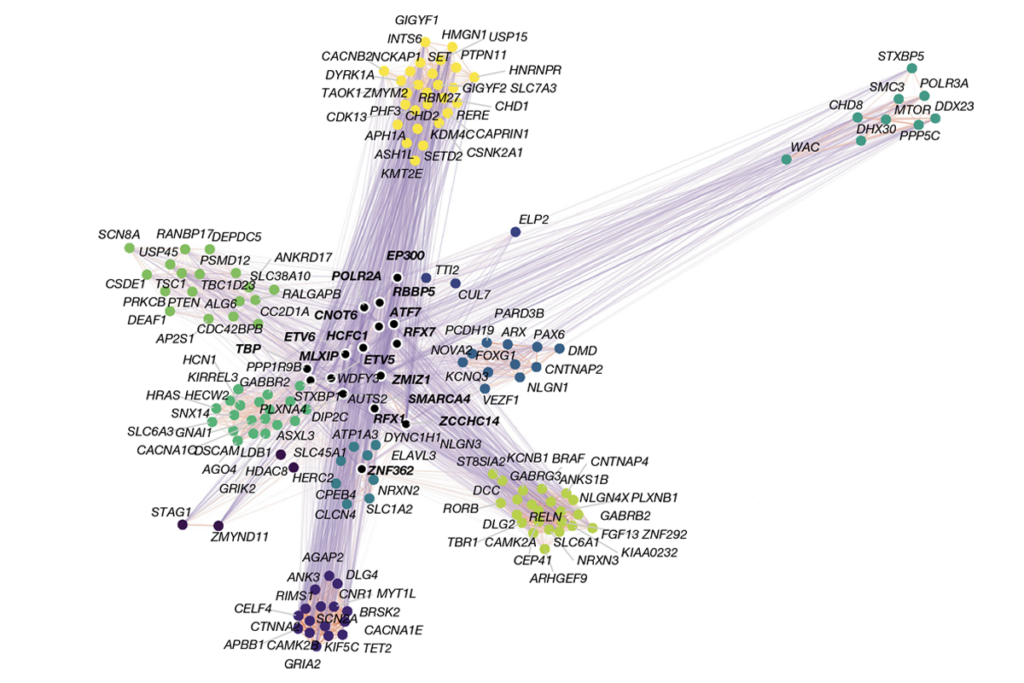

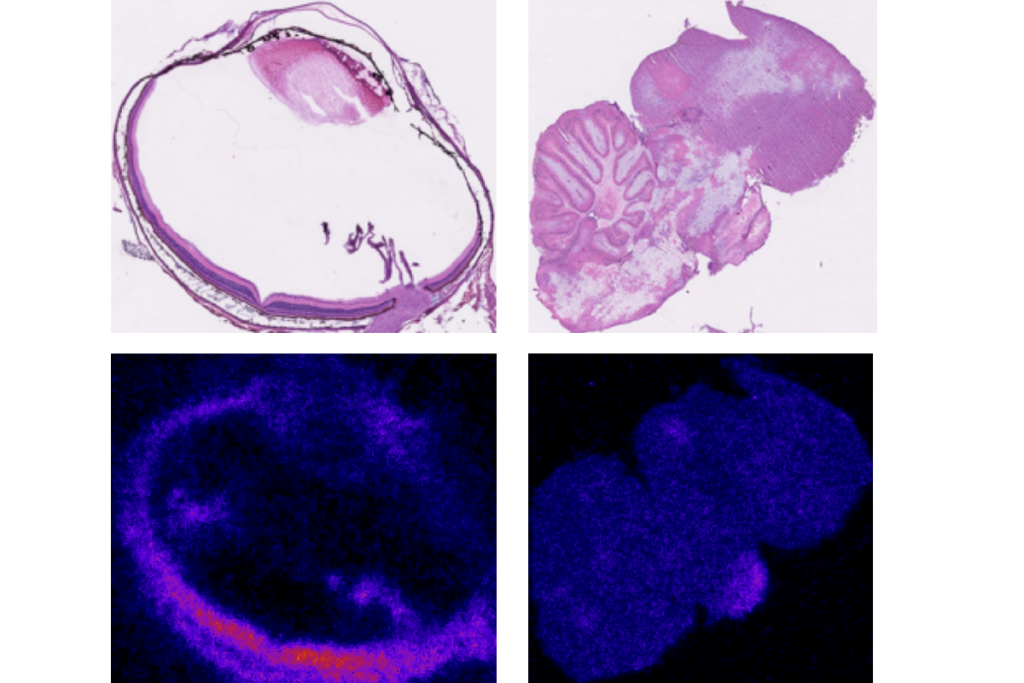

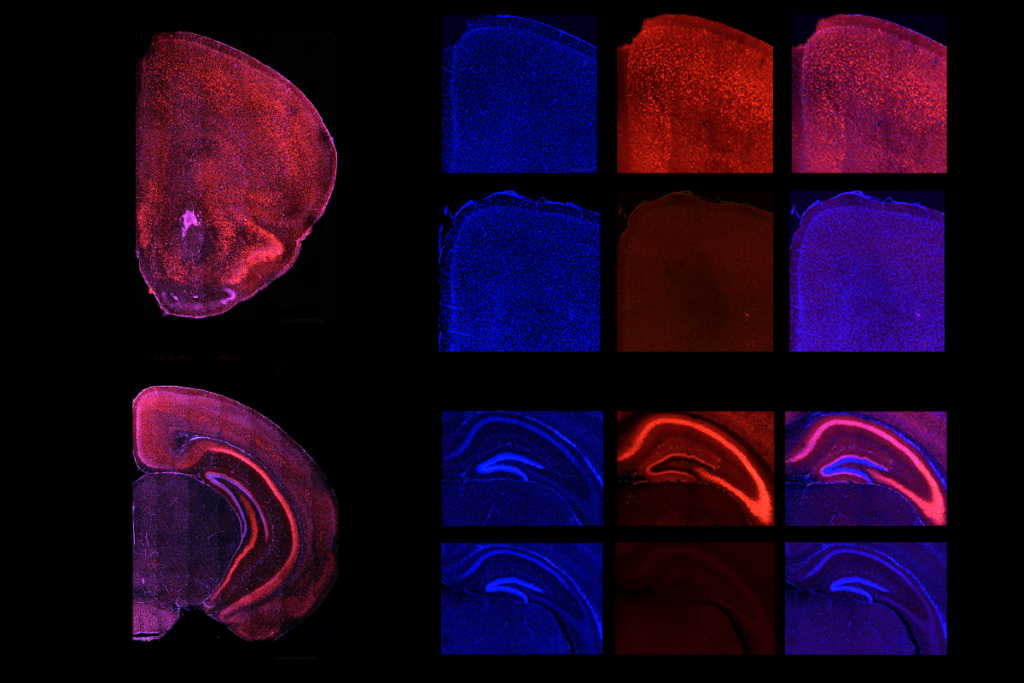

The work employed a novel optogenetic tool that enabled the team to turn off neurons deep in the hypothalamus of mouse pups. After being separated from their mothers for three hours, the pups vocalized more using distinct patterns when reunited with their mothers than did pups that had not been separated, a process controlled by oxytocin neurons in the pups’ hypothalamus, the team found.

“It would make sense if oxytocin is on both sides of this: making moms want to take care of their pups that are calling, and making pups call in a manner that makes mom want to take care of them,” Donaldson says. “Then we have this sort of convergence where oxytocin is once again doing everything.”

M

ice use ultrasonic vocalizations to communicate, cries that “are extremely powerful and drive a lot of animal behavior,” says Robert Froemke, professor of genetics at New York University, who was not involved in the study.For example, the pups’ vocalizations can elicit strong activation of oxytocin neurons in their mothers’ hypothalamus, previous work shows. To spur this communication, the team behind the new study separated 15-day-old pups from their mothers for three hours.

“If you really want to look at the motivation to seek out care from mom, then this is a great paradigm,” Donaldson says, because it triggers a state of “‘Oh, my God, Mom’s not here. I need her.’”

During separation, pups increased their distress calls, which were tightly linked to oxytocin neuron activity in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, the researchers found using two different techniques. This brain structure regulates stress responses and other homeostatic processes. When reunited, the pups again increased their ultrasonic vocalizations, particularly when they were close to their mothers. Pups emitted two main types of state-dependent vocalizations, one emitted before or after nipple attachment and another associated with nipple attachment and feeding.