Most male mammals do not dote on their young and may even attack them, but some African striped mice actively feed, groom and nuzzle their own and even others’ pups.

These profound behavioral differences come down to a single gene: agouti. This gene controls pigment production in the hair or skin of many animals. But in African striped mice, it also acts as a volume knob to silence caregiving circuits in the brain, according to a study published today in Nature.

“It’s remarkable that this one gene is able to lead to a dramatic change in behavior,” says Robert Froemke, professor of genetics, neuroscience and otolaryngology at New York University, who was not involved in the work.

Male African striped mice that live in isolation for roughly 2 months after weaning tend to nurture pups later in life, even those that are not their own, whereas their peers that live with other mice tend to be indifferent fathers or even infanticidal, the study found. The fatherly mice express lower levels of agouti in the brain compared with their more aggressive counterparts, the study shows.

“Agouti, we think, is a molecular integrator of environmental experience,” says study author Ricardo Mallarino, associate professor of molecular biology at Princeton University.

Despite the fact that only about 5 percent of mammalian species show fatherly behavior, parental care may be the default mode in striped mice, the research suggests. Both males and females use the same brain circuitry to care for their young, but enhanced agouti expression in the brain suppresses these instincts in the former.

“It’s not that male parenting behavior is upregulated in some circumstances, it’s actually the default pathway that is repressed in some circumstances,” says Catherine Dulac, professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, who was not involved in the work.

T

African striped mice dwell across southern Africa. In arid regions, they live in mixed-sex groups of up to 30 individuals, but young males may also venture out on their own in search of a mate. In lusher regions, all males tend to lead a solitary existence.

Growing up alone is stressful to most mice, so “we had fully expected that the solitary guys would be aggressive, and what we found was actually the opposite,” says study investigator Forrest Rogers, a postdoctoral researcher in Catherine Peña’s lab at Princeton University. “This study was one surprise after another.”

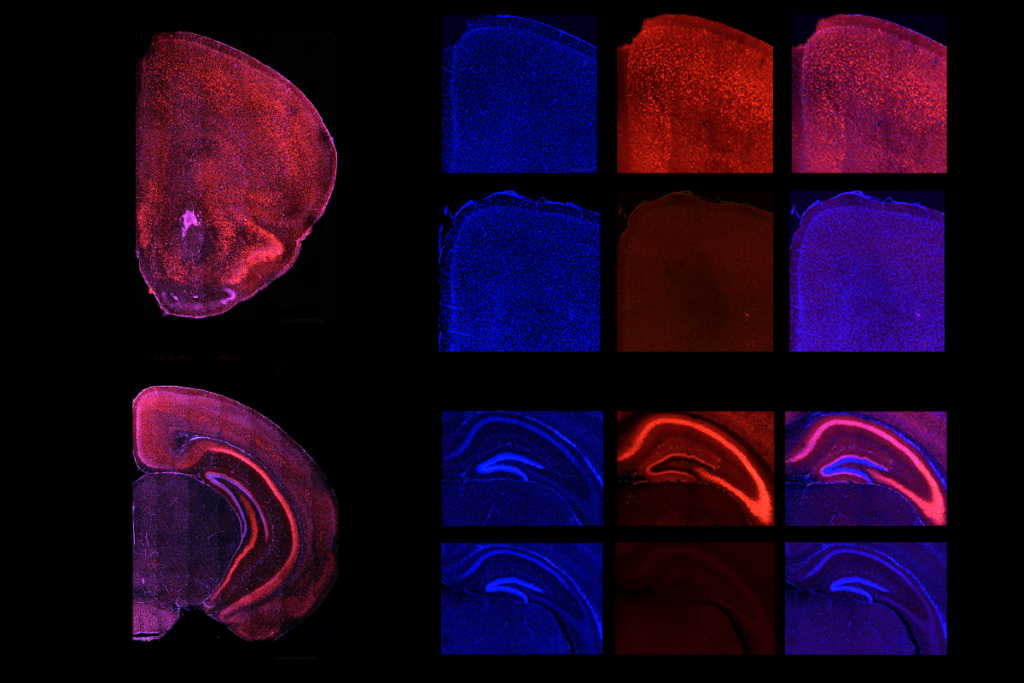

Exposure to pups increased neural activity in the medial preoptic area (MPOA) of adult male mice, regardless of whether they lived on their own or in a group. But the doting ones show higher MPOA activity levels than the aggressive ones.

The MPOA is critical for parenting in female rodents and undergoes significant changes during pregnancy. The MPOA of male striped mice doesn’t undergo such changes, and yet they still display strong parental behavior. The neuronal cell types found in group-housed and solitary mice were also similar, indicating that the basic circuitry was similar between the groups.

“We did not find that dads require novel circuitry to be brought online, which tells us that every brain has what it needs already,” says study author Catherine Peña, assistant professor at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute. “We did not find that they even have evolution of novel cell types within this necessary brain region, the MPOA.”

W

Agouti encodes agouti signaling protein (ASIP), which has never before been shown to be involved in parental behavior, he adds.

ASIP, which is known to bind to and activate melanocortin receptors, likely acts through these receptors to alter behavior, the study suggests. Nonpaternal mice express higher levels of melanocortin receptors in their MPOA.

And ASIP seems to be singularly important for modulating paternal behavior. Boosting its levels in the brain using a viral strategy made male mice less interested in pups. Some even became aggressive.

The agouti-related protein (AgRP)—which, as the name suggests, is closely related to ASIP—acts on the MPOA to depress maternal behavior and increase feeding behavior when food is scarce, previous work shows.

But increased hunger did not alter paternal behavior in male African striped mice, the new study shows.

Removing aggressive males from the communal living arrangement and housing them on their own for 16 days decreases agouti levels in their brain and makes them more tolerant of young mice. “This isn’t static,” Rogers says. “It’s something that can be changed by the environment.”

T

Reproductive behaviors are energetically expensive, so it might be useful for animals to be able to integrate environmental cues to alter their internal state, Rogers says. But it remains an open question if other mammals, including humans, have similar molecular integrators; the MPOA and agouti both exist in other mammals, though there is currently no evidence that they function similarly in other species, he adds.

The connection to the real behavioral ecology of the mice is also complicated, says Neville Pillay, professor of animal behavior at the University of the Witwatersrand, who was not involved in the study. It’s not exactly clear how the laboratory conditions map onto the conditions that mice encounter in the wild. African striped mice that live in groups display alloparental behavior, where both males and females take care of the young.

It’s also not clear which environmental cues boost agouti once mice encounter pups, or how being among other mice affects the brain. The upstream signals that cause changes in agouti expression, and the downstream effects on behavior, are the subject of future research, Mallarino says.

Agouti may interact with other molecules known to be involved in parental care or social behaviors, such as oxytocin and vasopressin, Froemke says. The researchers “didn’t detect any changes in gene expression in those systems, but it doesn’t mean that there aren’t changes in dynamics and release,” he adds.

Ultimately, this work shows the power of studies in non-model organisms, Mallarino says. “By studying nontraditional model species, we can make profound observations about behavior.”