Common brain malformation confers high risk for autism

About one in every three adults who lack a brain structure called the corpus callosum meet the diagnostic criteria for autism, according to a study published 25 April in Brain. However, not all of these people develop symptoms in early childhood, as is typical in autism.

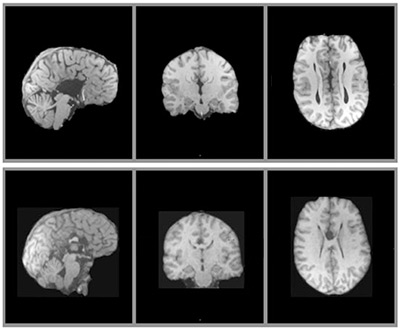

Information exchange: Like some people with autism, those missing part (bottom) or all (top) of their corpus callosum have trouble integrating social cues.

About one in every three adults who lack a brain structure called the corpus callosum meet the diagnostic criteria for autism, according to research published online 25 April in Brain1. However, not all of these people develop symptoms in early childhood, as is typical in autism.

Roughly 1 in 4,000 people are born lacking all or part of the corpus callosum, the thick bundle of nerve fibers that connects the two hemispheres of the brain. Individuals with this condition, called callosal agenesis, often have social difficulties and struggle with subtle aspects of language such as jokes and puns.

This is because the lack of a corpus callosum slows down a person’s ability to integrate disparate pieces of information from different brain regions. “For adults, the most pervasive form of rapid problem-solving we have to do is social,” says study leader Lynn Paul, senior research scientist at the California Institute of Technology Emotion and Social Cognition Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Other studies have found that individuals without a corpus callosum show symptoms consistent with autism, but this is the first to apply gold-standard methods to diagnose autism. Conversely, individuals with autism tend to have a small corpus callosum.

The new data go beyond this correlation to suggest that callosal abnormalities contribute to causing the disorder.

“Agenesis of the corpus callosum has to be at least a very strong risk factor for having autism,” says Thomas Frazier, director of the Center for Autism at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, who was not involved in the study.

The results bolster the connectivity theory of autism, which holds that the brains of people with autism have defective long-range connections. The corpus callosum is one of the largest, strongest long-range connections in the brain. “I think it really solidifies this link between [abnormal] brain connectivity and having autism,” Frazier says.

Detailed look:

In the study, Paul and her colleagues administered the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) to 26 adults who lack a corpus callosum and 28 who have high-functioning autism. Of the 26 participants with callosal agenesis, 8 meet diagnostic criteria for autism, as do all 28 participants with an autism diagnosis.

The study “applies the classic autism diagnostic tools to this callosal agenesis sample, and that’s never been done before in a rigorous way,” says Elysa Marco, assistant professor of neurology, pediatrics and psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the work.

Although 18 of those who lack part or all of the corpus callosum do not meet diagnostic criteria for autism, most of them show subtle social deficits, suggesting that the condition affects these individuals as well.

The researchers also assessed symptoms of generalized anxiety, social anxiety and depression in the participants, as well as their ability to recognize faces and emotions. The participants also completed questionnaires about general autism symptoms, empathy and interest in rules and systems. “It’s very comprehensive phenotyping,” Frazier says.

Finally, the researchers administered the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) to the parents of 22 of the individuals with callosal agenesis, asking them about the participants’ symptoms in childhood. Only 3 of these participants would have qualified for an autism diagnosis as children, they found. Those who meet autism criteria in childhood tend to have more language problems as children compared with those who only meet the criteria as adults.

“The surprise was parsing out the group that appears to have the earlier onset, the idea that there is a subset that has a more classic autism profile,” Paul says.

Traditionally, to receive a diagnosis of autism, individuals must show characteristics of the disorder in the first three years of life. But Paul says the later onset of symptoms is consistent with her observations in children with callosal agenesis. Many of these children show relatively typical development as toddlers and preschoolers, but struggle by around age 10.

“That delay, I think, maps onto it being more of a long-range and, in this case, inter-hemispheric connection problem,” Marco says. That is, as social interactions become more complex, those who lack a corpus callosum struggle to integrate social information from both hemispheres.

Others disagree with this interpretation of the results, saying that looking back at childhood symptoms may not capture the most accurate picture of the onset of social deficits.

“I think the much more likely scenario is that, developmentally, we didn’t understand their symptoms very well when they were younger,” Frazier says. “Now we’re understanding their symptoms better.”

The best way to resolve this conflict is to follow a group of individuals with callosal agenesis over time. Routine ultrasounds now enable diagnosis of callosal agenesis before birth. “We could really watch a cohort develop and see where things diverge among these groups,” Paul says.

Researchers could also compare the developmental patterns of young children lacking a corpus callosum with those of ‘baby sibs,’ or younger siblings of children with autism, who are at an increased risk of developing autism themselves.

The new study raises other questions, as well. The number of participants is not large enough to determine whether the risk of autism is different for those who lack the entire corpus callosum or only a part of it.

A 2012 study found that individuals with autism are more likely to have abnormalities in parts of the corpus callosum that connect brain regions important in social behavior2. But another study found that the wiring changes don’t necessarily align with the regions that are missing in people lacking part of the corpus callosum3. Larger studies would also be necessary to work out the genetic links between autism and callosal agenesis4.

References:

1: Paul L.K. et al. Brain 137, 1813-1829 (2014) PubMed

2: Frazier T.W. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 42, 2312-2322 (2012) PubMed

3: Owen J.P. et al. Neuroimage 70, 340-355 (2013) PubMed

4: Sajan S.A. et al. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003823 (2013) PubMed

Recommended reading

Building an autism research registry: Q&A with Tony Charman

CNTNAP2 variants; trait trajectories; sensory reactivity

Brain organoid size matches intensity of social problems in autistic people

Explore more from The Transmitter

Cerebellar circuit may convert expected pain relief into real thing