Early interventions, explained

The accepted wisdom in autism research holds that early intervention offers the best promise for an autistic child’s well-being. But how effective are these therapies?

In 1987, psychologist Ole Ivar Lovaas reported that he had created a therapy that would make the behavior of some autistic children indistinguishable from that of typical children by 7 years of age1. His approach, applied behavioral analysis (ABA), involves hours of drills each day, in which children are rewarded for certain behaviors and discouraged from others.

But Lovaas had overstated his case: Of the 19 children in his study who were treated, only 9 went on to meet typical developmental milestones.

Still, given the dearth of treatments for autism, ABA quickly became popular and is now the most common behavioral therapy for autism — but it is not without controversy. ABA also forms the basis for most interventions delivered early in childhood. The accepted wisdom in autism research holds that early intervention offers the best promise for an autistic child’s well-being. But how effective are these therapies?

Here’s what researchers know about early intervention.

What are the main types of early intervention?

ABA is the most popular of the therapies offered early in childhood. ABA now refers to a broad group of therapies that use reward to encourage and reinforce a set of skills.

One such treatment, the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM), applies the techniques of ABA during play to help a child express feelings, form relationships and speak. By facilitating positive interactions, the therapy is designed to help the child build social-emotional skills alongside cognition and language.

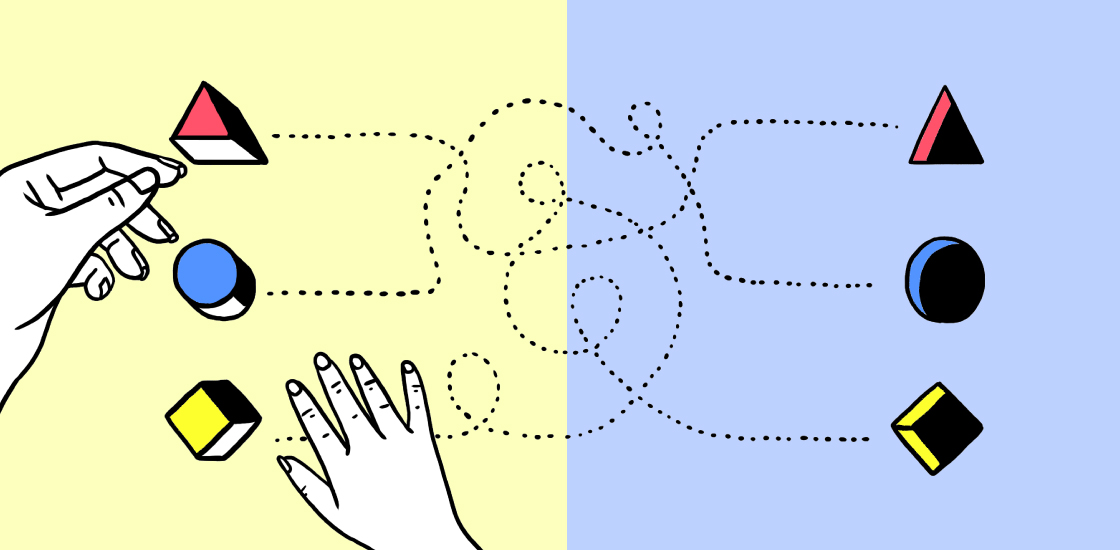

Another leading intervention based on ABA, called pivotal response treatment (PRT), is also applied during play. It targets pivotal areas of development, such as motivation and self-management, rather than specific skills. This approach teaches a child how to respond to verbal cues. For instance, when a child requests a toy, the therapist or parent asks the child to name the toy; the child gets the toy once she complies.

Other treatments based on ABA target specific skills. For example, a therapy called Joint Attention, Symbolic Play, Engagement, and Regulation (JASPER) focuses on social communication skills; in Discrete Trial Training (DTT), therapists break target skills down into smaller steps. Another approach, called Strategies for Teaching based on Autism Research (STAR), applies PRT and DTT to classrooms.

A newer class of therapies targets social communication difficulties. Instead of using rewards to change behaviors, these therapies give a child practice engaging in social interactions. For example, in a therapy called Preschool Autism Communication Trial (PACT), therapists teach parents to recognize and respond to their child’s attempts to communicate.

How long does it take for early intervention to be effective?

Children receive ABA-based early intervention for up to 40 hours per week. The therapies may continue for several years, becoming shorter and less frequent at about age 5.

In light of this time commitment, parents are often tempted to try less established therapies billed as quick fixes or miracle cures, says Stephen Camarata, professor of hearing and speech sciences and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Helping children learn skills can take a long time, however. “That’s not a quick process, and it’s not a magical process,” he says.

Is there evidence that these therapies are effective?

Surprisingly little. Most early interventions have not been tested in randomized controlled trials, says Tony Charman, chair of clinical psychology at King’s College London. For instance, only one of the five studies included in a review last year was randomized; that study suggested that autistic children who receive therapy are more likely than untreated ones to be placed in mainstream classrooms2.

Even when controlled trials exist — as they do for JASPER and ESDM — they often have too few participants to lead to firm conclusions about efficacy, Charman says. In a large analysis published earlier this year, trials that showed some positive effects had small sample sizes and effect sizes3.

And, as in other areas of autism research, studies of early intervention have a diversity problem. Many studies predominantly include white children, so the results may not apply to other autistic children. Few studies compare therapies with each other, or track whether their effects last.

“We don’t have very much evidence about what these interventions do after 20 years,” says Sally Rogers, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis.

When should treatment start?

Early intervention typically follows an autism diagnosis, so its start depends on the age of diagnosis. In the United States, most children are diagnosed after age 4.

It may be possible, and preferable, to start treatment even earlier in some cases. So-called ‘baby sibs,’ or children who have an older sibling with autism, are at an elevated risk for the condition. A study last year showed that two years after receiving five months of a video-based therapy to improve communication between parents and children, baby sibs showed some improvement in their skills4.

A 2014 study of 11 infants showed that those who received an adaptation of ESDM between 7 and 15 months of age had fewer autism features at age 3 than those who did not receive therapy. The following year, a review of nine studies hinted that behavioral treatments improve social communication when applied in children under 2 years5.

How have behavioral treatments for autism changed over time?

Behavior therapies historically involved seating a child at a table for hours and asking her to name objects pictured on flash cards. Rigid drills like this can improve language, for instance, or ease repetitive behavior6.

But over the past 20 years, therapies have moved to more familiar environments, such as the child’s bedroom or playroom. Often, a child gets to choose the activity — coloring at a table or playing with trucks, for example. The intervention is often integrated into other aspects of the day, as parents have become increasingly important partners in reinforcing behaviors.

Many researchers emphasize that the most effective interventions are those that can be adapted to an individual child. Children have specific developmental goals — related to language, say, or social skills — and start at various developmental levels.

“Interventions are not one-size-fits-all,” says Lynn Koegel, clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California, who is one of the creators of PRT.

What’s next for the field?

When an intervention proves effective, researchers often don’t know which components of it led to the improvement, making it difficult to incorporate it into new therapies. Some teams are trying to pinpoint the ‘active ingredients’ of successful treatments.

In 2015, a research team tested three components of the STAR method in 119 schoolchildren7. One component, PRT, is associated with improvements in the students’ cognitive ability, the team found; the other components, DTT and a method called ‘teaching in functional routines’ are not.

A better understanding of the most important components of a therapy may provide clues to how to improve it. It would also help clinicians customize the therapy without inadvertently omitting the crucial ingredient.

References:

- Lovaas O.I. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 55, 3-9 (1987) PubMed

- Reichow B. et al. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5, CD009260 (2018) PubMed

- French L. and E.M.M. Kennedy J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 444-456 (2018) PubMed

- Green J. et al. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 1330-1340 (2017) PubMed

- Bradshaw J. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 778-794 (2015) PubMed

- Lovaas O.I. et al. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 6, 131-165 (1973) PubMed

- Pellecchia M. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 2917-2927 (2015) PubMed

Corrections

This article has been modified from the original. The wording has been changed to correct the implication that all early intervention therapies are based on ABA. The previous version also incorrectly stated that a video-based therapy lasted for two years instead of five months.

Recommended reading

Amina Abubakar translates autism research and care for Kenya

Post-traumatic stress disorder, obesity and autism; and more

Cortical structures in infants linked to future language skills; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Multisite connectome teams lose federal funding as result of Harvard cuts