Imaging study links immune genes to anxiety

Mice missing any of 11 genes involved in the immune response show differences in brain anatomy that track with anxiety.

Mice missing any of 11 genes involved in the immune response show brain changes that track with anxiety.

Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Previous studies have hinted that immune pathways are disrupted in autism. And in utero exposure to the mother’s immune response is associated with an increased risk of autism.

“We know the immune response can have an effect on the brain,” says Shoshana Spring, project manager at the Mouse Imaging Centre at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada, who presented the work. “We wanted to know what type of effect it’s having.”

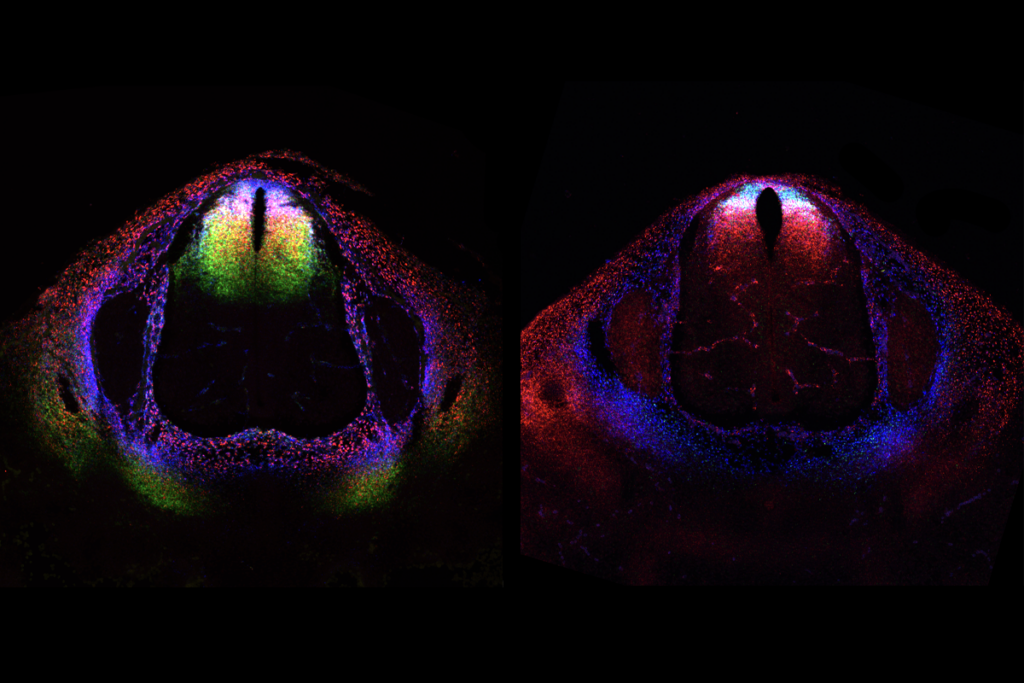

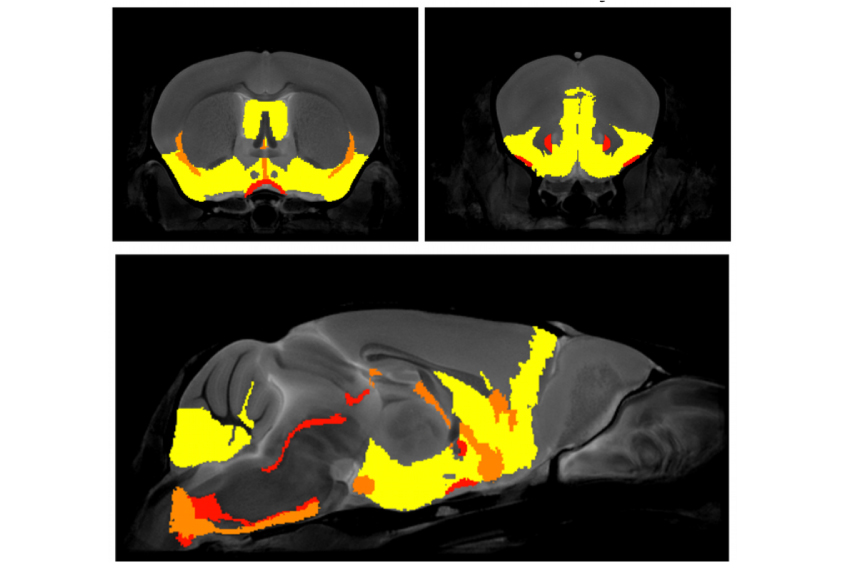

Spring and her colleagues used magnetic resonance imaging to measure the volumes of 104 brain regions in 11 strains of mice. (They studied at least 15 males and 15 females from each strain.)

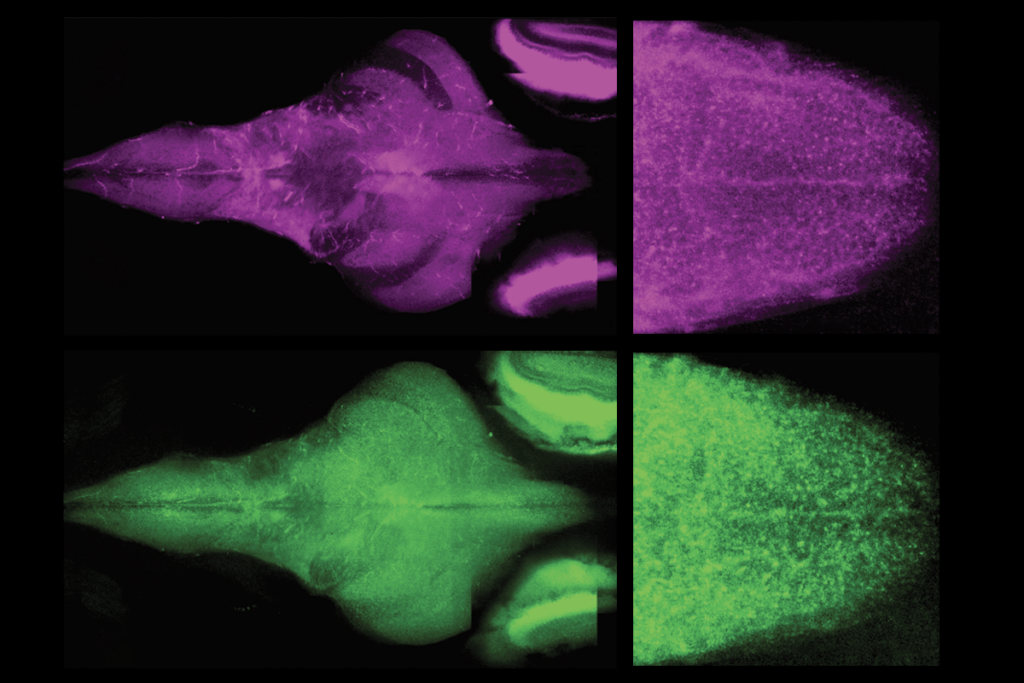

The strains each lack one of 11 genes that play a role in immunity.

Some of the genes encode molecules called interleukins, which can either promote or dampen inflammation. One such molecule, interleukin-6, has been implicated in autism. Other genes, such as CD4 and CD8, characterize T cells, which protect the body from invaders.

Brain alterations:

All 11 strains show brain abnormalities, the researchers found. But the location and severity of the abnormalities vary widely.

Six of the strains show signs of anxiety; the other five strains do not. When the researchers grouped the strains based features of anxiety, patterns of brain volume abnormalities emerged.

The six strains that have anxiety features show alterations in the amygdala, which processes fear, and the hippocampus, which is involved in memory. These changes are consistent across the sexes. Both regions have been implicated in anxiety and autism, which often co-occur.

“Neuroanatomy is affected by the genetics, and it’s affected in a way that’s consistent with the behavior,” says Darren Fernandes, a graduate student in Jason Lerch’s lab at the University of Toronto, who helped to analyze the data.

The findings suggest neuroanatomy is a “middle ground” between genetics and behavior, Fernandes says. Researchers could use a similar approach to identify brain changes associated with behavioral features in mouse models of autism.

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles

NIH scraps policy that classified basic research in people as clinical trials