Language regression in autism tied to motor milestones

Autistic children who lose words reach key milestones earlier than autistic children without language regression.

Autistic children who lose words reach key milestones earlier than autistic children without language regression, according to a new study1.

The idea of ‘regressive autism’ is controversial: Some researchers argue that all autistic children lose language or other skills at some point and that, like autism itself, regression is on a spectrum. Others say regression characterizes a subtype of children with autism.

The new study supports the latter hypothesis.

“Our findings suggest that there is something unique in this [regression] group, something about their development that is different from the development of children with no regression,” says lead investigator Idan Menashe, assistant professor of public health at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel.

Menashe and his colleagues studied children who spoke at least three words for at least a month before losing that vocabulary. They found that these children began to crawl, walk and talk at the same age, on average, as typical children do, suggesting that they were developing typically before the regression’s onset. By contrast, autistic children without language regression gained these skills several months later and were already on a different developmental trajectory.

Because the definition of regression is contentious, the team narrowed their investigation to consider only language regression, and they confirmed the loss in three independent sources: parent questionnaires, clinical records and follow-up parent interviews.

They screened 218 autistic children but included only those for whom all or none of the three sources reported language regression: 36 autistic children with language regression and 104 without. Those without were included only if they had no history of any type of regression.

“They were capturing information about development and skill loss from multiple sources to really converge on: Is this truly regression?” says Robin Kochel, associate director for research at Texas Children’s Hospital Autism Center in Houston, who was not involved in the study. “It was important for them to have the cleanest, clearest comparison between kids who do and do not have that sort of developmental presentation.”

Baby steps:

The autistic children with language regression crawled 1.5 months earlier, walked three months earlier and talked about eight months earlier, on average, than autistic children without regression, the researchers found. That timing is similar in age-matched neurotypical controls.

“They seem to have typical development in terms of times of key developmental milestones,” Menashe says.

Because physical development can influence motor and language development, the researchers also measured head circumference, height and weight in a subset of participants. They found no differences between autistic children with and without regression and neurotypical controls, although autistic children without regression were significantly more likely to have low muscle tone.

Children with language regression were diagnosed with autism earlier than those without, the researchers found, perhaps because their parents sought medical help when they noticed the skill loss. The findings appeared in August in Autism Research.

The analysis also shows that children with language regression require significant support, according to criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. But previous studies have found mixed results on whether regression predicts how autistic children fare later in life2.

“I do think it’s worth making a big deal out of this phenomenon that kids have some skills that seem to drift away,” says Catherine Lord, professor of human development and psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study. “But I think trying to say who that occurs in and that it’s associated with later worse outcomes is probably much harder to do.”

Lord says the study’s binary comparison between children with and without language regression may not capture the true picture, because some skill losses may be temporary or fall below the three-word threshold the researchers used.

“By grouping kids into ‘no regression’ and ‘regression,’ we’re probably missing something that’s important,” she says.

Accounting for children who don’t fall neatly into either category is easier said than done, however. “We looked at the two extremes knowing we might miss a lot of people that might not fit into these two groups,” Menashe says. “Maybe it is actually one continuum, but it’s very difficult to define.”

References:

Recommended reading

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

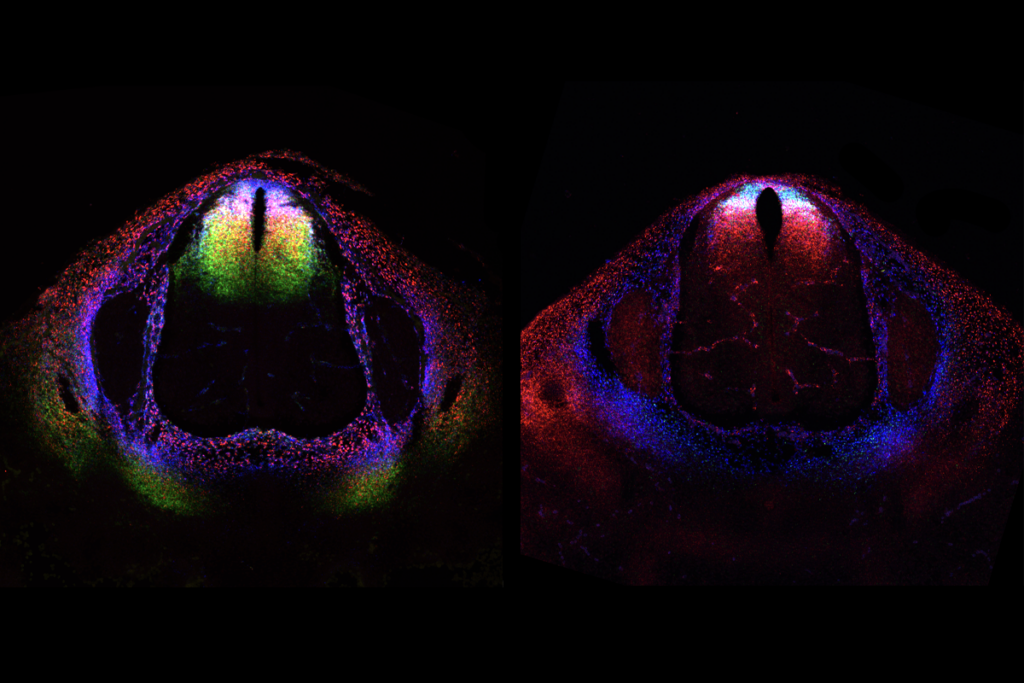

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

Explore more from The Transmitter

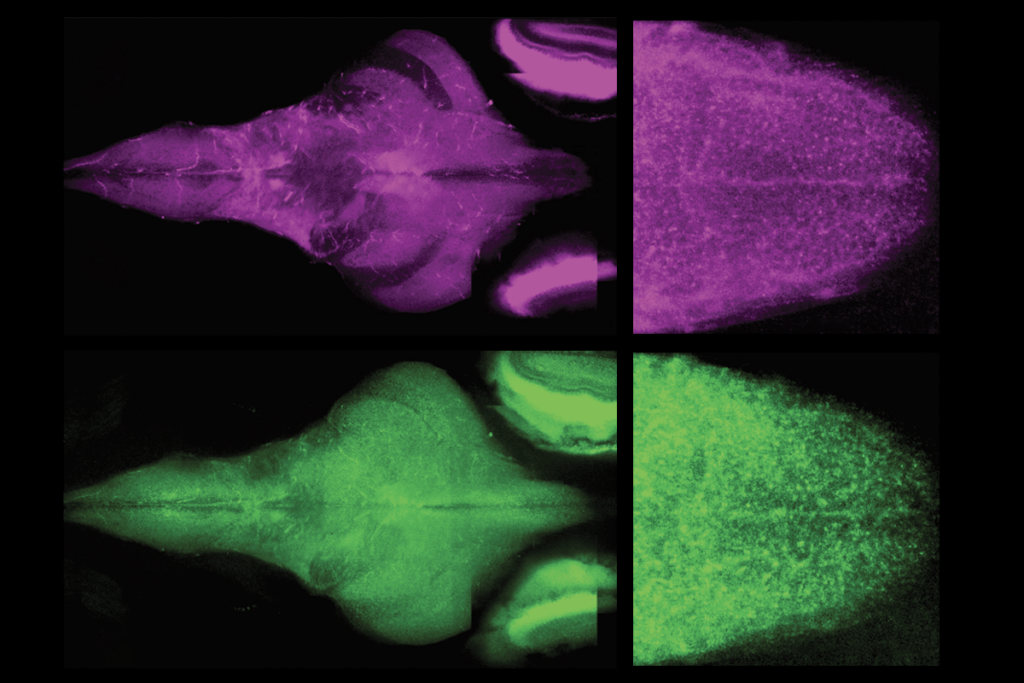

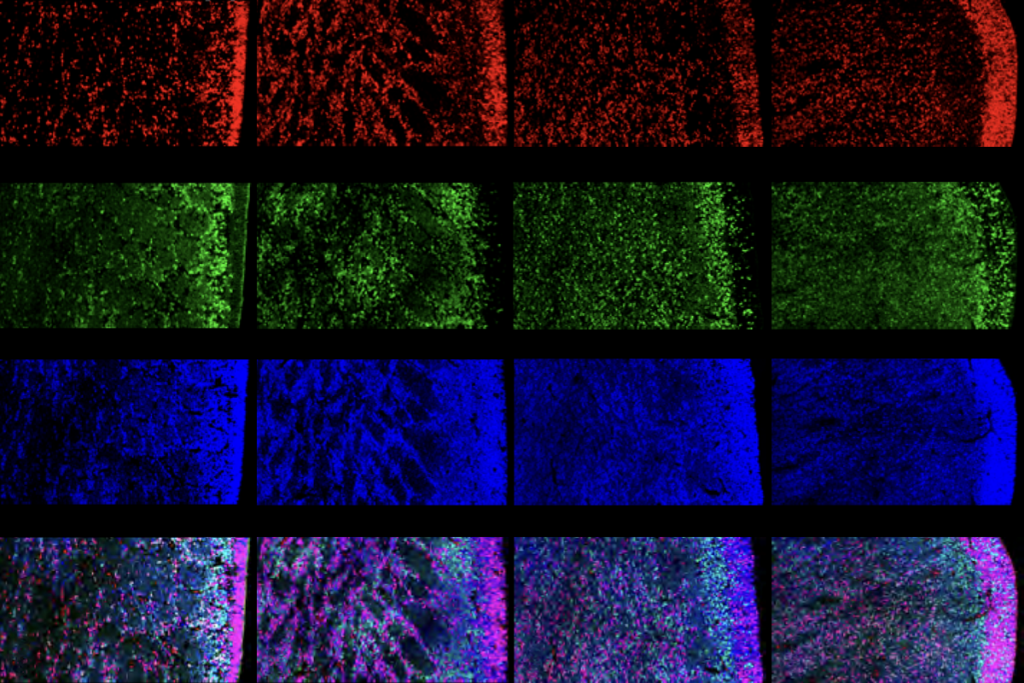

Cell atlas cracks open ‘black box’ of mammalian spinal cord development

Betting blind on AI and the scientific mind