Large postmortem brain study unearths clues to schizophrenia

A massive collection of brain tissue reveals common genetic variants that influence gene expression in the brain.

A massive collection of brain tissue reveals the common genetic variants that influence gene expression in the brain1.

Applying the findings to schizophrenia suggests that the condition stems from a pile-up of mild variants that affect many genes.

The new work builds on studies of DNA variants that are common among people with schizophrenia. These genetic differences often fall outside of genes, so researchers have had trouble tracing how they increase schizophrenia risk, says co-lead investigator Bernie Devlin, professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

“If you amass a sufficient number of samples in a disorder like schizophrenia or autism, then you’re going to discover these common variants — but that doesn’t link them at all to genes or neurobiology,” Devlin says. “You have no idea what those variants are actually doing.”

The new study, the largest of its type for schizophrenia, ties 20 variants to both changes in the expression of particular genes and to schizophrenia risk. The approach, described 26 September in Nature Neuroscience, also may shed light on autism and related conditions.

“It’s a potentially very powerful approach to combine information about gene expression, genetic regulation and disease association,” says Lauren Weiss, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved with the study.

Tissue trove:

To study gene expression changes in brain conditions, the researchers formed the CommonMind Consortium. The partnership has amassed a collection of postmortem brain samples from 1,150 individuals. Of these, the new study used 258 from individuals with schizophrenia and 279 from controls.

“One of the keys to the study is the sample size, which is a lot larger than previous studies,” says Dan Arking, associate professor of genetic medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who was not involved in the study. The dataset is about four times larger than that of the largest similar study of autism, he says.

Overall, the researchers found that the schizophrenia brains show altered expression in 693 genes. All these differences are slight, ranging from a 3 to 33 percent change.

The findings indicate that schizophrenia stems from small, cumulative changes in the expression of many genes, says study investigator Menachem Fromer, associate professor of genetics and genome sciences at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Stronger effects for individual genes might emerge with more brains or when researchers narrow their search to particular cell types, he says.

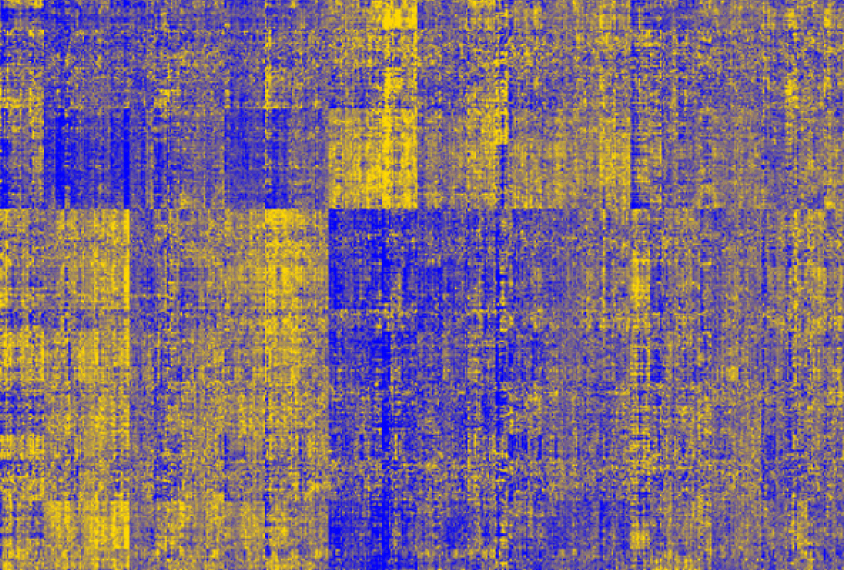

The researchers looked for common variants that influence gene expression. They sequenced the DNA from pooled brain tissue samples from 467 individuals. They then measured messenger RNA levels for thousands of genes in these brains.

Small heads:

Combining these data, they associated thousands of variants to changes in gene expression. They compared this list of variants to a set of 108 variants tied to schizophrenia. The researchers discovered 20 statistically significant variants that are on both lists.

They focused on five variants that each regulate a single gene. They increased or decreased the expression of each of the five genes in zebrafish embryos to mirror the effect in the human brain. For three of the genes — FURIN, TSNARE1 and CNTN4 — these tweaks alter the fish’s brain development, resulting in a small head.

Rare, harmful mutations in 8 of the 33 genes that the schizophrenia variants affect have been seen in people with autism. This overlap suggests that the two conditions share genetic risk factors. However, people with schizophrenia do not carry an excess of harmful mutations in these same genes.

The discrepancy hints that severe mutations in certain genes lead to autism, which manifests in childhood, whereas a milder hit precipitates schizophrenia in early adulthood, says Menachem.

Because the brains in the study are from elderly individuals, the findings may not reflect gene expression changes that occur in childhood. This may limit the data’s relevance for autism.

References:

- Fromer M. et al. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1442-1453 (2016) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025

Neuroscience’s leaders, legacies and rising stars of 2025