A gene that is poorly expressed in people with certain neurodevelopmental conditions is also essential for sleep, according to a new study in fruit flies.

Many people with autism or other neurodevelopmental conditions have trouble falling asleep and slumbering soundly. This difficulty is often viewed as a side effect of a given condition’s core traits, such as heightened sensory sensitivities and repetitive behaviors in autism.

The new work, though, offers evidence that sleep problems may stem directly from the same genetic changes that underlie these conditions.

“Sleep should be viewed as a core phenotype in these sorts of conditions — it’s not something that’s just emerging from broader problems,” says lead researcher Matthew Kayser, assistant professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

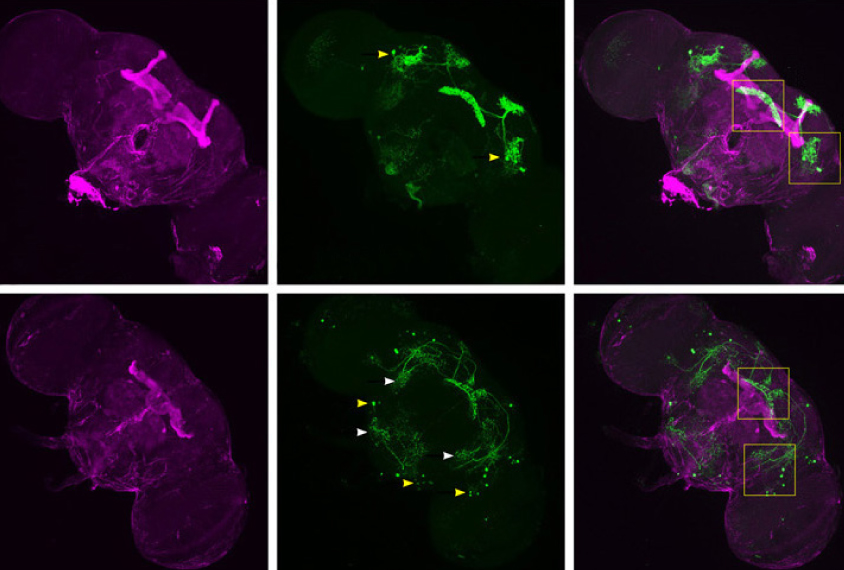

Flies engineered to have low expression of the gene ISWI have underconnected sleep circuits in the brain and disrupted sleep, Kayser and his colleagues found. ISWI is the fly version of the human genes SMARCA1 and SMARCA5, which regulate the expression of other genes by changing the structure of chromatin, or DNA in its coiled-up form. Many genes that alter chromatin structure have strong ties to autism and related conditions.

Modifying the flies to express SMARCA5 normalized their sleep circuits and behaviors, the team also found.

This is the first paper that links sleep problems with chromatin regulation, says Lucia Peixoto, assistant professor of biomedical sciences at Washington State University Spokane, who was not involved in the study.

Offbeat rhythm:

Kayser and his colleagues evaluated the sleep patterns of flies engineered to have any one of 421 gene mutations linked to neurodevelopmental conditions, including autism.

The flies with low expression of ISWI slept less than typical flies do, the researchers found, and when they did sleep, it was fragmented.

The low-ISWI flies also had problems with circadian rhythm, the internal clock that cues animals about when to eat and sleep throughout the day. And they failed a memory test, forgetting that they had learned to avoid taking a drink of a sugary solution that, in previous instances, was immediately followed by something bitter.

Like many people with neurodevelopmental conditions, the flies had atypical social behaviors: Male flies did not display courtship behavior around female flies, and female flies did not form social clusters when large numbers of them were put into an arena.

The sleep problems ceased when the team engineered the low-ISWI flies to express SMARCA5, but the flies still performed poorly on the memory task. Flies engineered to express SMARCA1, on the other hand, did better on the memory task but still had sleep problems. But neither issue improved in flies that express a variant of SMARCA5 found in people with a neurodevelopmental condition.

“This is a very elegant way to demonstrate that SMARCA5 is responsible for at least some of the issues” seen in people with neurodevelopmental conditions, says Philippe Mourrain, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California, who was not involved in the study.

Lowering ISWI expression through fly “teenagerhood” resulted in altered sleep circuits and disrupted sleep, suggesting that this later period of development is essential for the circuits to form properly, Mourrain says.

The findings were published in February in Science Advances.

Sleep screens:

“[The findings] suggest that we should be paying more attention to sleep deficits in neurodevelopmental conditions,” says study investigator Naihua Gong, a graduate student in Kayser’s lab.

Sleep problems may be one of the earliest signs of a neurodevelopmental condition in babies — apparent before issues with social communication can be measured, Gong says. Using poor sleep to screen for early signs of autism and other conditions “might be a way to identify people who might be more [neurodevelopmentally] vulnerable.”

And because disrupted sleep can exacerbate other problems associated with neurodevelopmental conditions, such as cognition, improving sleep as early as possible could have lasting benefits, Mourrain says.

Kayser, Gong and their colleagues have a study in press that describes a group of children who have SMARCA5 mutations and a neurodevelopmental condition, further bridging the gap between the fly and human research.

“We’re hoping to look more closely at those kids and their sleep patterns going forward,” Kayser says.