Preprint server bioRxiv gets boost from Facebook billionaire

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has pledged to provide financial support for bioRxiv, a website where researchers can share manuscripts before peer review.

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative announced plans Wednesday to support bioRxiv, a website where researchers can share results before the drawn-out process of peer review.

Facebook billionaire Mark Zuckerberg and his physician wife Priscilla Chan launched the initiative in 2015. Last year, they pledged $3 billion toward curing cancer and other conditions. Neuroscientist Cori Bargmann leads the initiative’s science strategy. Wednesday’s announcement did not disclose the amount of funding for bioRxiv, which is run out of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York.

Physicists have been posting preprints for decades, primarily to arXiv, but biologists have had to choose from one of eight preprint services, each with different policies and infrastructure.

Given the myriad of different options for posting preprints, “it’s becoming more and more challenging not only to find a [particular] preprint, but also to know whether the preprint conforms to certain standards,” says Jessica Polka, director of ASAPbio, a nonprofit group that aims to promote the use of preprints in the life sciences.

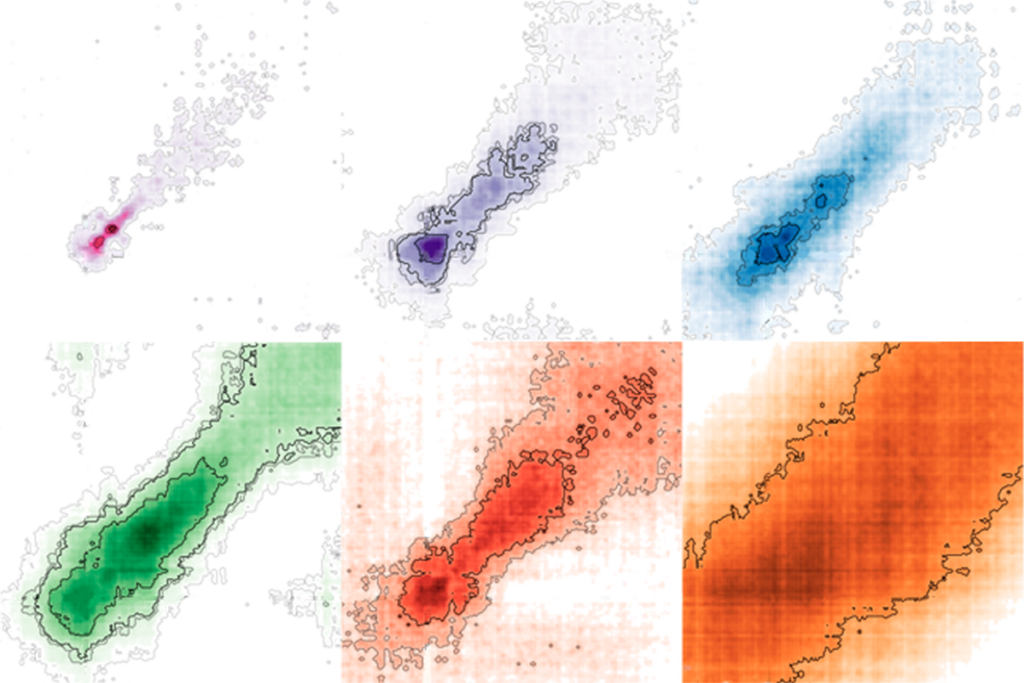

Wednesday’s announcement makes bioRxiv a frontrunner in this race, and reflects a response to the growing call for transparency in science. So far this year, biologists have posted more than 1,000 preprints each month to bioRxiv and other preprint servers, such as PeerJ Preprints and F1000 Research. This is about five times the rate at which they posted preprints in 2012.

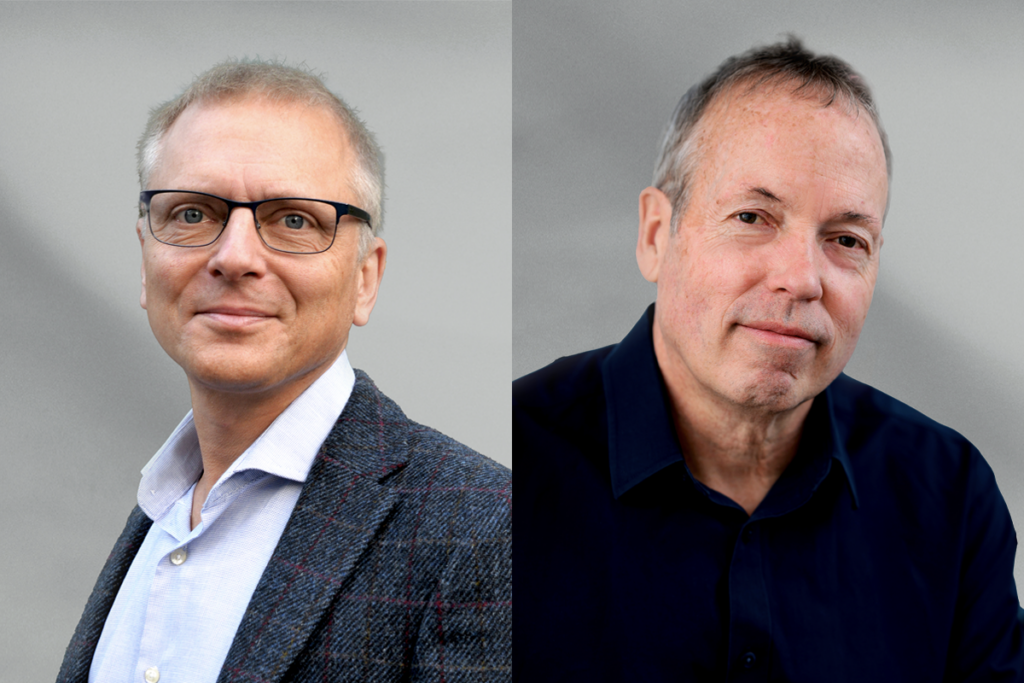

“Preprints in the life sciences have finally gained a momentum that they haven’t had before,” says John Inglis, executive director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, who co-founded bioRxiv in 2013.

Major funders of biomedical research, including the U.S. National Institutes of Health in March and the U.K. Wellcome Trust in January, have announced that they will allow scientists to reference their preprints in grant applications. And many major journals allow authors to submit work described in preprints; some have even hired editors to comb preprints for potential submissions.

Preprint plethora:

Four preprint or preprint-like servers have launched in the past six months alone, by organizations including the Wellcome Trust, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Center for Open Science. In March, Cell Press debuted a preprint service called Sneak Peek that offers previews of papers under review at Cell, Neuron and its other journals.

The dizzying array of different preprint servers has prompted calls for a central service to organize them all. In February, ASAPbio received $1 million from the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust to create a server that would aggregate preprints and make them easier to use.

For instance, Polka says, a central server could format preprints so that scientists could search them for specific genes, proteins or for links to certain conditions. It could also allow users to download preprints and analyze them for patterns.

“The ability to build new research tools on top of preprints is where the future will be,” says Johanna McEntyre, head of literature services for the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge, England, which oversees Europe PubMed Central, a repository analogous to the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s PubMed.

Some researchers have said bioRxiv should become the primary biology server because it is the most popular so far, but Inglis is noncommittal. He plans to use funds from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative to test some of the tools that would make preprint servers more useful.

Data sharing:

Many researchers use bioRxiv as their primary means of communicating findings to other scientists; they still publish in journals, but only to impress hiring committees and grant reviewers.

“bioRxiv is today a main tool for the communication of our scientific results to colleagues,” says neuroimaging specialist Roberto Toro of the Pasteur Institute in France. “Publication in bioRxiv is for science; publication in traditional journals is for business.”

Some autism researchers use bioRxiv to get timely feedback they can integrate into the manuscripts they submit to journals. This is especially useful for younger researchers who must look for jobs and fellowships while waiting for publication of their work, says Varun Warrier, a graduate student in Simon Baron-Cohen’s lab at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. “Having the preprint online means that people can judge the quality of my work for themselves,” Warrier says.

Other scientists, though supportive of preprints, are wary of their growing popularity. “My main concern is that people forget that preprints haven’t undergone peer review,” says Jon Brock, a cognitive scientist at Macquarie University in Australia and an academic editor for the open access journal PeerJ.

About 60 percent of preprints posted on bioRxiv are eventually published in journals, Inglis says. The rest may never be intended for publication — or are submitted but don’t pass muster with peer reviewers. There’s no way to tell the difference between the two.

In the meantime, ASAPbio is asking scientists for feedback on draft guidelines for a governing board that will help set standards for preprints; the organization plans to hold elections for this board in July.

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

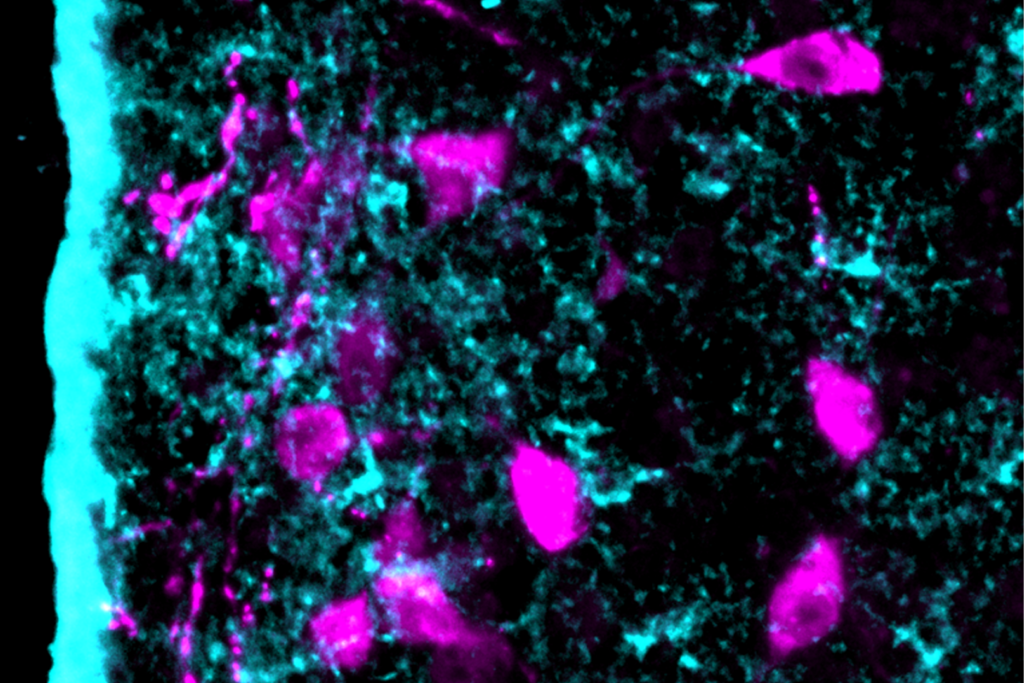

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers

Two neurobiologists win 2026 Brain Prize for discovering mechanics of touch