Race, class contribute to disparities in autism diagnoses

Black and Hispanic children are less likely than their white peers to meet criteria for an autism diagnosis.

The prevalence of autism continues to increase across the United States, regardless of socioeconomic class, according to a new study1. Overall, black and Hispanic children are less likely than their white peers to have an autism diagnosis.

The findings highlight persistent racial disparities in autism prevalence: White children are about 19 percent more likely than black children and 65 percent more likely than Hispanic children to be diagnosed with autism.

Autism prevalence in the U.S. has more than doubled since 2002. Researchers have looked to changes in the condition’s diagnostic definition and greater awareness among parents as possible explanations for this rise.

They have also assumed that access to good schools and medical care would explain much of why white children and those of high socioeconomic status are more likely than black and Hispanic children and those of low socioeconomic status to be diagnosed with autism.

The new study upended many of these assumptions.

The findings suggest that socioeconomic status doesn’t fully explain the differences in prevalence across race and ethnicity.

“Everything is a little bit more complicated than we thought,” says Maureen Durkin, lead researcher and professor and interim chair of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “We’ve been trying to understand the racial and ethnic difference in prevalence, and it isn’t so simple as that it’s explained by social class.”

Prevalence climbs:

Durkin and her colleagues analyzed surveillance data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network. The CDC database includes health and education records for more than 1.3 million children at age 8. Of those, the clinicians identified 13,396 children who either had an autism diagnosis or would meet the criteria for a diagnosis.

The team used census data on the proportion of adults with college degrees in a neighborhood as a proxy for socioeconomic status. They stratified the results by race and ethnicity to determine whether socioeconomic status alters their findings on prevalence.

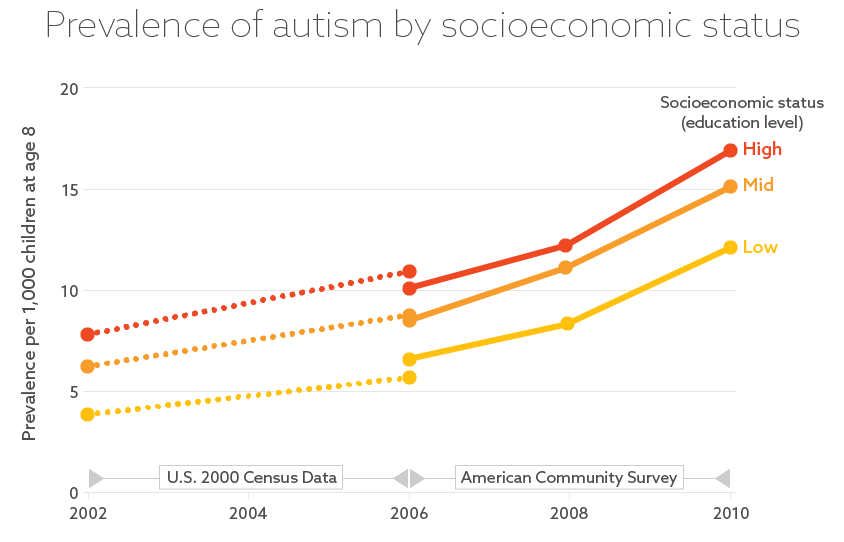

Autism prevalence rose almost evenly among high-, middle- and low-socioeconomic groups between 2002 and 2010, the researchers found. The rates increased from 3.9 to 9.3 per 1,000 children in the low-socioeconomic group, from 6.2 to 11.6 in the middle class and from 7.9 to 13.4 in the high-socioeconomic group.

This was a surprise. The research team had expected that prevalence in the high-socioeconomic group in 2002 was “the true prevalence” and that the numbers for that class would stabilize over time, Durkin says. “But it really didn’t.”

Across the classes, prevalence roughly doubled in the three racial and ethnic groups: It rose from 6.7 per 1,000 children to 13.2 among white children, from 5.9 to 11.1 among black children and from 3.9 to 8 among Hispanic children.

This suggests that autism awareness and access to services are increasing across racial and ethnic groups, but the prevalence among minority children still lags behind that of white children.

Persistent gaps:

When the researchers looked more closely within each racial and ethnic group, they found that differences in prevalence across socioeconomic classes either stayed the same or became smaller.

For instance, the difference in prevalence between low- and high-income white children decreased over the study period. This suggests low-income white families are becoming more aware about autism over time, Durkin says.

Among blacks and Hispanics, however, the gap between low- and high-socioeconomic classes remained level.

Surprisingly, the rate of autism among black children in the high socioeconomic group was higher than that among white or Hispanic children between 2002 and 2010.

“It’s intriguing that in higher-social-class blacks, there’s no shortage of autism,” Durkin says. “Black children are much more likely to be in the low-socioeconomic group than white children,” she says. The finding supports the idea that lack of access to diagnostic services contributes to the overall lower prevalence of autism in black children.

There is no biological reason for autism prevalence to differ across racial and ethnic groups, says Katharine Zuckerman, associate professor of general pediatrics at Oregon Health and Science University, who was not involved in the research.

“The fact that we continue to see this in all of our prevalence studies in the U.S. suggests to me that we really just don’t know what the true prevalence of this condition is, particularly among minority kids,” she says.

Parents in some groups may be less concerned or aware about autism, and may not seek out a diagnosis for their child, says Craig Newschaffer, director of the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute in Philadelphia. Newschaffer was not involved in the study but wrote a commentary about the work in the same issue of the journal2.

Another study published this month suggests black parents report fewer concerns about social problems, repetitive behaviors and other autism features than white parents do3. Language barriers may contribute to the lower prevalence among Hispanic children. A study from October showed that a child’s race or ethnicity isn’t related to the time between diagnosis and treatment4.

Parental age may also contribute to the disparities. Advanced paternal age is associated with an increase in autism risk, and fathers of white children tend to be older than those of black or Hispanic children.

References:

Recommended reading

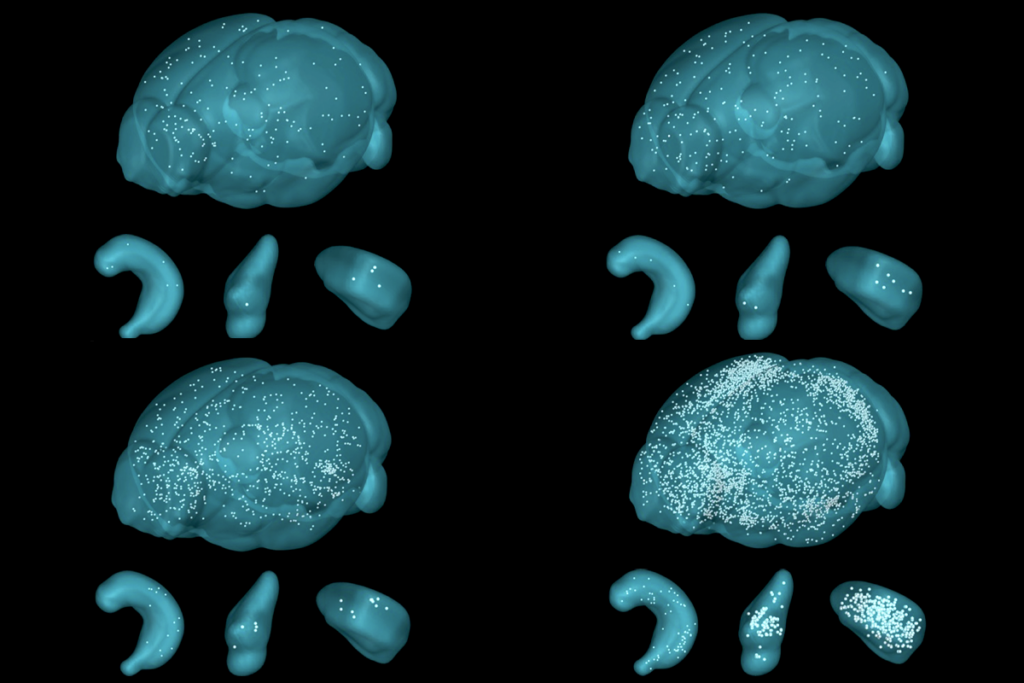

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Fly database secures funding for another year, but future remains in flux

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky